It would be easy to write about many factors of The Night of the Hunter at length. There’s the part about how Charles Laughton, Yorkshireman, so fluently worked in the field of Southern Melodrama—and never directed another film. There’s how much of our knowledge of the making of the film seems to be taken from what Robert Mitchum made up whole cloth for his autobiography. There is, of course, the film’s use of religion! But what struck me as I watched it on the big screen for the first time was how much the film is a story of sexual repression.

We know nothing of the marriage of Willa (Shelley Winters) and Ben (Peter Graves) Harper. She later claims to have hounded Ben to robbing the bank by demanding perfume and finery, but Ben implies it was some sort of half-baked protest against the bankers during the Depression and an attempt to keep his children from suffering the way he’s seen other children suffer; either one is plausible enough, I suppose. What we know for sure is that Ben did rob a bank, for whatever reason, and is hanged for the crime, because two people died during the robbery. And Willa is left widowed with two small children.

Willa works at the candy store owned by the Spoons, and Icey Spoon (Evelyn Varden) is the first intimation that all is not placid under the surface. It’s not merely that Icey harangues Willa about remarrying, though goodness knows that’s irritating enough. It’s the way she makes the whole idea sound like a business transaction, merely the only way to properly raise children. (I’d like to turn my own mother, widowed when we were about the age of these kids, loose on her for Icey’s insistence that you can’t raise children without a father.) There is, in these moments, an intimation that Willa’s first marriage was a passionate one.

Conversely, we have seen the ominous Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum) talking over his actions with the Lord. Crimes, yes, but Harry doesn’t think of them that way. Certainly not as sins. And here is where we immediately learn that there is something wrong with Harry Powell.

There are things you do hate, Lord. Perfume-smellin’ things, lacy things, things with curly hair.

Mitchum twists his face as he delivers the line, showing disgust, yes, but also bewilderment, bewilderment at men who are swayed by such things. And yet in his very next action after explaining about the widows he’s already killed—all in the Lord’s name, of course—he goes to the burlesque house where he’s arrested for stealing a car. He is surrounded by men captivated by the dancer—naturally, we don’t see much come off, and by the time the stripping presumably starts, Laughton keeps the camera turned on Mitchum. Mitchum is a blank in this scene, fleeting disdain and revulsion on his face at times but mostly just watching. The other men are perhaps also blank, men who paid money for a show that is supposed to titillate but who seem almost bored instead.

We know, of course, that we wouldn’t be seeing these two without the certainty that they would meet up. Now, the odds that a man serving a month for car theft and a man on Death Row would share a cell seem slight to me, but there they are, and Powell finds out about the widow—and the money. He is interested in the money, but when he prays the matter over, the widow is certainly part of his calculations.

One of the film’s most obvious moments comes when Harry Powell comes into the Spoons’ store in search of Willa. He says he was “employed” by the state, tells her that he knew her husband. And that he’s just passing through and wanted to give her comfort. Icey Spoon clearly has a specific kind of comfort in mind, and she tells Harry that he won’t get any of her fudge unless he stays for the social she’s making it for. Indeed, as she’s talking to him, the pot of fudge boils over.

You don’t have to be a Freudian to recognize that fudge for symbolism, after all. Icey finds this stranger appealing. Sure, he’s Robert Mitchum, but I think at least part of it is that he’s also a stranger. Mysterious. With that veneer of holiness that makes a woman’s talking to him seem more respectable. In the old phrasing, she promptly begins throwing Willa at his head, because Willa is an acceptable surrogate for Icey’s own feelings.

Then, at the social, Icey is talking to the other women, none of whom ever respond. They are an audience surrogate in that moment; she’s really talking to us.

When you’ve been married to a man for forty years you know all that don’t amount to a hill of beans. I’ve been married to Walt that long and I swear in all that time I just lie there thinkin’ about my canning.

Walt doesn’t excite her. She is physically attracted to Harry Powell, and she doesn’t quite know what to do about it. So she wrangles and maneuvers—including offering young John (Billy Chapin) some of that fudge, which he tells her he doesn’t want—to get Willa and Harry alone, so things can go according to her plan. Even though she herself has said that “A husband’s one piece of store goods you never know ’til you get it home and take the paper off,” she’s encouraging Willa to try it out.

There’s a great deal of conflict between her rapid insistence on Willa’s remarriage—she and Harry have only known each other a few days when they become engaged and not much longer before they’re married—and her pious claiming that marrying for lust is a bad idea.

A woman’s a fool to marry for that. That’s somethin’ for a man. The Good Lord never meant for a decent woman to want that. Not really want it. It’s all just a fake and a pipe dream.

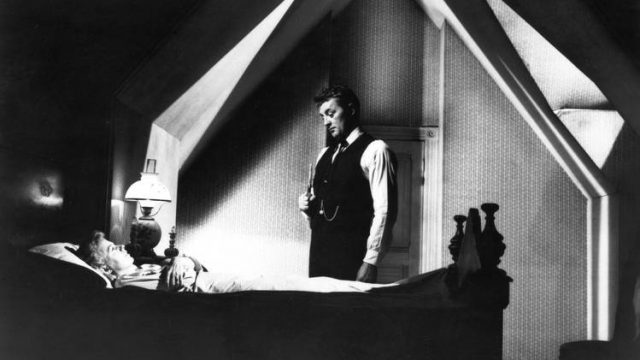

It’s okay for men to lust, but women can’t. But what is the situation with Harry driven by, if not lust? And Harry certainly knows it. We see poor, tragic Willa primping for her new husband on her wedding night, and Harry cruelly rejects her.

Now go look at yourself yonder in that mirror. Do as I say. Look at yourself. What do you see, girl? You see the body of a woman, the temple of creation and motherhood. You see the flesh of Eve that man since Adam has profaned. That body was meant for begettin’ children. It was not meant for the lust of men!

When Willa says that confessing her concern that Harry is only interested in the money her husband stole, she says she’s overflowing with “cleanness.” Really, she feels that she can accept her lust since she believes Harry’s interest is in her, and presumably her body. But Harry rejects lust as a denial of being clean. He gets Willa to stand up in his meetings and denounce her own bodily desires, to defame her first husband for giving into them. He may have said the money was to keep his children whole, but obviously, it was all about sex.

Which is why, I think, the healthiest character in the movie is Rachel Cooper (Lillian Gish). Oh, yes, she’s trying to keep Ruby (Gloria Castillo) from going out with boys, but it’s not because she disapproves of sex per se; it’s because she doesn’t think Ruby is smart enough to handle herself. She’s not wrong, either; it’s Ruby’s desire to be loved and noticed that causes her to betray John and Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce). She confesses her sin, and Rachel is understanding.

You were looking for love, Ruby, in the only foolish way you knew how.

Sex may be foolish, but Rachel doesn’t see anything inherently wrong with it. She will neither kill for it nor die for it, but love is worth both. And so she, like the children she speaks such love for, abides.