My momma done tol’ me, when I was in knee pants,

My momma done tol’ me: son…

One of the most famous opening lines in all of American music, so much so that many people confuse the first five words for the title. An irony, since the song’s actual title so eclipsed the name of the film it was to appear in that the producers eventually changed the film’s title instead. The film had started production as Hot Nocturne, an adaptation of Edwin Gilbert’s unproduced play of that name, and briefly transitioned to New Orleans Blues before Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer delivered the moody number that eventually took over the film, and the country, with five Billboard-charting versions within the year: “Blues in the Night.”

I needed a separate post to talk about this song because there’s so much here to talk about. It’s a classic work, maybe my favorite we’ll cover in this series, but its genesis, its function as a work of pop-blues, its context in the film, and its subsequent life are all necessarily and impossibly intertwined with the cultural and political issues of the American music scene, and when I say “impossibly,” I don’t mean in the way that limp cultural criticism seeks out easy political relevance. I mean that these issues aren’t so much subtext as explicit text, and the movie in particular waves these issues in front of us like a bullfighter’s muleta, daring us to charge.

So charge we must. Let’s start with the first appearance of the song, a scene from Blues in the Night where the movie’s ostensible heroes, a struggling jazz band hopping train cars around the South to find the “real” jazz experience, have been arrested in St. Louis and housed in a segregated jail cell, opposite a group of black prisoners (as I mentioned in part one, there were two Oscar-nominated in songs in 1941 delivered by black vocalists, and both were behind bars, if that’s any indication what we’re working with here.) Warning: while there’s (mercifully) no blackface here, the second half of the clip below involves a mix of stock footage and actors in stereotypically racist scenarios.

The first time I heard this version was a revelation: I was familiar with the many, many, many covers and parodies of the song, but never the original item, and this is so far superior to any version that followed that I can’t shake how good it is. I get chills every time I hear this performance, especially that of the soloist, an uncredited William Gillespie in his first and only distinctive film role.

Its context in the film immediately presents us with two elephants in the room, the dreaded duo of “authenticity” and “appropriation.” Again, this isn’t so much subtext as text: the white musicians hear what they consider the genuine article sung by a black prisoner, so they memorize the song and start performing it in their own sets, to great success. This is as straightforward a dramatization of appropriation as you could hope for, abandoning as they do the song’s “author” in his cell while making a career off his work. They themselves become better musicians because they’ve managed to tap into the “authentic” product of Southern African-American culture.

Of course the song was only tangentially any of those things, and one of the deep complexities of this moment in the film, and of the heritage of this song, is that it’s an inauthentic blues song written by a Jewish New Yorker to sound like a quasi-authentic blues song to be put in the mouth of a black Southerner (who was actually a Julliard-trained singer) and coopted by white musicians named (sigh) Nickie and Jigger. It wears its inauthenticity on its sleeve: since Harold Arlen (the greatest) never met a song he couldn’t make needlessly complicated, he twisted the blues structure around his own musical interests and came up with a hybrid that’d never be mistaken for the real thing… that is, until the song’s real-life popularity helped reshape the mainstream (esp. white) image of blues.

Arlen himself is situated right in the middle of the thorniest issues of early twentieth-century American racial-cultural integration. His father, a Jewish cantor who taught him the art of improvisation, rented out part of their home to a black family, whom Arlen grew up alongside. He cut his teeth as a performer under a black composer, Will Marion Cook, (himself a student of Czech composer Antonín Dvořák, himself famously influenced by African-American folk music, layers on layers on layers) and established his reputation as the house composer for Cotton Club revues, a white composer writing for all-black performances for all-white audiences in Harlem. One of the Cotton Club’s most famous performers, Ethel Waters, called him the “Negro-est” white man she’d ever met. The great Pearl Bailey considered Arlen her favorite composer: she’d even made her Broadway debut in one of Arlen’s all-black musicals, St. Louis Woman. None of this is to paper over Arlen’s place in the racial hierarchies of clout and material success — he was, after all, the kind of person who could enter the Cotton Club through its front entrance, who could put his name to “black” music and have it treated with a seriousness that often eluded his black colleagues (more on this below), who even wrote pieces in Hollywood specifically for blackface performance, collaborating with Al Jolson in the mid-30s. Even at its most positive and productive, Arlen’s place in popular culture involves confronting some of our ugliest history, too.

Despite a decade working in the milieu of African-American music, “Blues in the Night” proved a real departure for Arlen, who’d never written a proper blues song: he considered his early “blues-y” masterpieces like “Stormy Weather” and “I Got a Right to Sing the Blues” to be torch songs, not blues as such. “Night” is perhaps the only song where the typically laconic Arlen admitted to doing his research. Unfamiliar with the genuine article except by overall environmental osmosis, Arlen turned to a colleague, W.C. Handy, who’d written the definitive textbook on southern blues, Blues: An Anthology (later republished under the better-known title A Treasury of the Blues). In Arlen’s version of the story, the typically fast-working composer studied Handy’s examples, identified the core structural elements, and managed to hammer out the rest of the song in a matter of hours. The story behind its lyrics is more legendary: unhappy with any of lyricist Johnny Mercer’s attempts at an opening stanza, Arlen noticed a stray scrap of text from what was supposed to be later in the song: “My momma done tol’ me.” Arlen and Mercer disagree about the precise timeline, but this is more or less how the song came together.

And what a song! Building from the conventional twelve-bar blues structure, a kind of formal lattice that allowed generations of blues composers to experiment and explore the latest innovations in tonality within the safety of a constrained environment, Arlen steadily introduces his own characteristic flourishes. The first twelve measures are mostly conventional, moving between the major-key tonic, subdominant, and dominant chords — though he does delay the first return to tonic by giving measure seven a II7-V7 progression and repeating that in measure ten. Still, there’s nothing yet especially radical here.

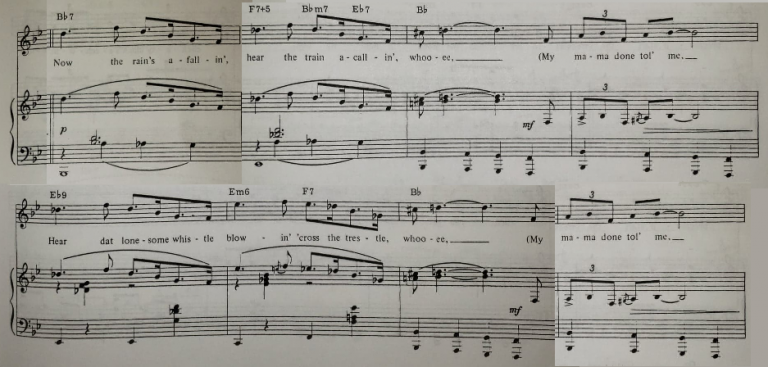

The second cycle of twelve strays much farther afield. Here are the first seven measures (note that Em6 in measure six is a mistake and should be Ebm6):

It’s the second and sixth measure here that are much more difficult to analyze, and show off Arlen’s background and the dense and ambiguous jazz chords he’s most known for. What Arlen seems to be doing is smashing together two separate but complimentary harmonies into a hybrid that performs two separate functions at the same time. On the one hand, we can analyze, say, the bass line of measure six and say that Arlen’s giving us another II7-V7 progression to bring us back to the home key, and it does indeed sound that way. On the other hand, we can say that he’s maintaining the conventional twelve-bar structure by giving us the subdominant Eb, but shaking things up by shifting it to Eb minor, and it sounds that way, too. But we’re talking about two different harmonies with two different functions: what kind of devilry is this?

The song’s third section is so far out of blues convention that the movie dispenses with it entirely. Apparently bored of the twelve-bar’s repetitive formula, Arlen introduces a eight-bar contrasting section that’s much more like his torch writing than anything blues-related. The overall arc of this gently swaying countersubject is to set up a dominant chord for our eventual return, so, zooming out, we get something like IV7-II7-V7… nothing really that weird. But in a typically Arlenian way, the path is beset with complex moves (there’s a Db7 serving as something like a Neapolitan chord for the secondary dominant of C7? I think?) and a melody that’s so much harder to perform than it sounds, forcing the singer to jump to and linger on prominent flat ninths. Oof. Whatever the case, the song finally returns to the twelve-bar structure, giving us an ending set of measures that are identical to the first. The movie, happy to be back on solid ground, includes this final section in full.

All of this is fine, but I really can’t praise the movie’s setting of the song enough. Too many covers of the song fell prey to the kitschy renderings: it’s one of the reasons I’d never given the song a lot of consideration in the past! Here, the a-capella performance feels revelatory, from Gillespie giving it his all to the also-uncredited background singers coming in with call-responses and supporting texture. The effect is (to me) genuinely haunting: without the relentless pulse of a band or rhythm section, the background voices coming in at 0:10 and 0:50 have the lonely sadness of that solo English horn at the end of Berlioz’s “Scène aux champs“, an aching echo coming from the distance.

The song was an immediate hit, one of those cases where everyone knew it was going to be big, and it was. Arlen’s circles certainly recognized what he pulled off. The song’s first-ever audience, who heard it in a private home performance, included Mickey Rooney, Mel Tormé, and lifetime Arlenophile Judy Garland, all of whom lavished praise on him and begged to learn the song immediately. After “The Last Time I Saw Paris” took home the unexpected Oscar, the winner, another Oscar (Hammerstein II), sent Arlen a postcard saying “You were robbed.” He and Kern just expected that Arlen would win. It was the obvious choice.

And to the extent that the Oscars matter, it was: Arlen had delivered something totally sui generis, a true classic, but not a work of conventional blues per se. Even leaving aside Arlen’s own background, research, and technical fiddling, it’s nothing like “the real New Orleans blues,” as the characters in the movie claim (I don’t know even know what that comment means, particularly in 1941, when the city hadn’t produced what we might call a distinctive local blues sound. Certainly, there were blues performers and important blues recordings made there, but nothing that even a trained ear would be able to pick out of as distinctively New-Orleanian versus, say, a more obvious candidate like Delta blues. For a movie that’s about authenticity — about the white insistence on authenticity in black music, sixty years before La La Land — it’s just another layer of inauthenticity, with the jazz-centric “New Orleans” serving as an easy metonymy for the entire Southern African-American musical tradition in all its flavors.)

In fact, the headlining black musician of Blues in the Night, bandleader and saxophonist Jimmie Lunceford, hated the song. The Mississippi-born Lunceford, who was playing to sold-out crowds in Memphis before he became a Cotton Club regular, wasn’t convinced by Arlen’s work but had no choice but to perform it in this, his first and only film role. Adding insult to injury, the Lunceford band’s big scene in the film is really a showcase for a white character, Leo the trumpeter, to prove the superiority of his talent. That’s right, the movie has a fictional white musician showing the real-life Lunceford band how it’s done! (he also insults New Orleans cooking, and there are some things that are just unforgivable.)

For all these reasons I laid out above, it’s impossible to talk about “Blues in the Night” without looking at the material ways that American racial politics affected the fates of everyone involved. When Arlen wrote the song, he was living in a sunny Los Angeles home with its own separate studio for composition, while Lunceford, despite a lifetime creating the real thing, found himself relegated to window dressing. “Blues in the Night” hit number one on the charts via a white performer, Woody Herman, while the film’s uncredited William Gillespie never got his breakthrough and, after a lifetime of smaller works and radio, spent the rest of his life back in Nashville working in a funeral home. In the end, it’s the Nickies and Jiggers who write the history. But history also has a sick sense of humor: forced to record a song he considered false from the get-go, Jimmie Lunceford’s band ended up with a major hit on their hands (chart-peaking at #4).

Inauthenticity had its benefits. Lunceford’s resistance to the song would prove something of an anomaly: “Blues in the Night” is one of the most recorded pieces in the Great American Songbook. Right out the gate with Cab Calloway‘s more exaggerated comic version, a stripped-down Louis Armstrong, or Arlen favorite Ella Fitzgerald‘s smooth-as-silk rendering, through the Hammond-organ improvisations of Jimmy Smith, an abstract Ray Charles, the updated big band of Quincy Jones, up to Van Morrison and the band Chicago and Tia Carrere as a cartoon Martian, and even deeper into the world of kitsch. I mean… take your pick.

Oh wait, before we go: there’s another wrinkle here. Jazz composer Mary Lou Williams later accused Arlen of taking the opening “Blues in the Night” riff from one of her own compositions, specifically the clarinet section of “Big Time Crip,” which comes in around the 0:45 mark in that recording. As a black woman with both minimal legal representation and little industry clout, Williams was a frequent target of “borrowings” (including from Jimmie Lunceford’s trumpeter, against whom she eventually won a small settlement), and asserted that Arlen’s was another. I’m not equipped to evaluate her claims here, but on a naïve listen, I’d say she has a case. Not an entirely open-and-shut case (“Big Time Crip” was published the same year as “Blues in the Night,” but she says that it was written years before and regularly played at the kinds of clubs Arlen frequented), but the riff is close enough that she could have had her day in court. If Arlen really did “borrow” the main riff, then it makes that scene in Blues in the Night an even more unwieldy palimpsest of ironies, nearly collapsing on itself.

I want to close with a brief note about the rest of the Blues in the Night soundtrack. Were it not for the cultural dominance of the title song, there’s a good chance Arlen’s other contributions might have made it to Oscar night instead. At one end we have the delightful stomper, “Hang on to Your Lids, Kids,” a song where you actually can hear the New Orleans influence: this has some pretty great Dixieland flourishes. Still, this is Arlen, so he finds fun ways to twist the line, like that delayed final cadence that forces an extra measure at the end of each cycle.

But I’m even fonder of “This Time the Dream’s on Me,” a jazz-torch that, while much simpler in construction than the usual Arlen special, is as gorgeously melancholy as anything he ever wrote. Unfortunately I don’t think the in-film performance by Priscilla Lane does the song much justice — Lane’s phrasings and enunciation choices leave a lot to be desired — but there are plenty of covers out there (for some reason the Annie Ross performance was recently highlighted by Korean boy-band BTS… I am old, don’t ask me to explain.) It’s treated like a second-tier Arlen song but really ought to be first-tier. It was a favorite of jazz legend Charlie Parker, who performed it frequently.

I love Harold Arlen, but I’m not an expert. For that I had to turn to other sources, mainly Edward Jablonski’s book Harold Arlen: Rhythm, Rainbows, and Blues, Walter Rimler’s The Man That Got Away: The Life and Songs of Harold Arlen, and Don McGlynn’s documentary Somewhere Over the Rainbow: Harold Arlen (available in full here); the latter includes interviews with Arlen himself. The material on Mary Lou Williams comes from Linda Dahl’s Morning Glory: A Biography of Mary Lou Williams. I also consulted online resources like Cafe Songbook. Everything else is linked in-text.