Michelle MacLaren, director of the upcoming Wonder Woman, has done journeywoman work on many TV shows, but it’s on Breaking Bad that she proved herself to be one of the best action directors (and quite possibly one of the best directors, period) working today. Breaking Bad is one of the most cinematic of shows, using framing, pacing, and (especially) colors to get its effects; perhaps no other show in all of television has so effectively used the widescreen frame. It’s benefited from the unifying mind and showrunning of Vince Gilligan and a stable of great directors, but MacLaren has been the best of all of them. She has crafted action sequences that stand with the best of cinema, and I’ll look at three of them here.

Good action sequences are becoming rarer and rarer these days. We are still very much in the age of Michael Bay and CGI, when most action directors equate “throwing more visual and sonic chaos on screen” with good action. A good action sequence has a choreography and elegance to it, and depends often on the limitations of the characters and what they can do and also on carefully giving information to the audience. (Recently I finished watching 24, and a persistent weakness in the action storytelling was giving too much information; often the action was shown from so many perspectives that any surprise or suspense was lost.) All these things factor into one of the most essential elements of cinema, and one that MacLaren has mastered: the sense of time.

In action films, many sequences derive their power from the Beat the Clock aspect; an action has to be completed before some kind of deadline passes, or an action has to be completed before another action is. It gives an urgency to what’s going on. Do that, and there’s no need for character or morality or any other interest; the adrenaline reflex of the audience will generate all the interest we need. Action films, like horror films, are primal in a way that other genres aren’t; they operate on us on a far deeper level than morality.

Like Baroque music, action films often work by alternating slow and fast tempi. Even the most relentless narrative (James Cameron’s Aliens comes to mind) will take breaks in between the action for characters to regroup, plan, or just plain breathe. Takeshi Kitano’s Hana-bi was perhaps the most extensive and daring version of this kind of pacing, an almost static film interrupted by incredibly short bursts of violence. This kind of pacing is most effective because the power doesn’t come from the speed of the action, it comes from the transitions into and out of the action, by the contrast between the action and everything around it. It’s another thing that MacLaren deploys so well, and so many other filmmakers don’t.

HERE BEGIN THE SPOILERS

“One Minute”

That sense of alternating pacing gets used in one of MacLaren’s best-known scenes: the attempted assassination of Hank (Dean Norris) at the end of “One Minute.” Alone in his SUV in a mall parking lot, Hank receives a disguised-voice call, telling him two men are on the way to kill him: “you have one minute.” The two men are the Cousins, who have been a presence since the first scene of this season (the third). Hank had turned in his gun earlier that day, so he’s defenseless and panicked in the car, watching the clock turn over from 3:07 to 3:08. (An inside joke–this is episode 3:08.)

Here MacLaren shows her first crucial decision: we do not clearly see the approach of the Cousins. At this point, we have a piece of information Hank doesn’t: we know what they look like. (Luis and Daniel Moncada give magnificent performances, looking like brother Terminators in shiny, steel-gray suits.) The first half of this sequence will be from Hank’s perspective, so MacLaren swings the gaze of the camera over many different people–any one of them could be the killer. We also get this obscured shot, and I can never tell if they’re the Cousins or not. Even though I know who to look for, I don’t know if I should be looking at this, so I’m exactly in Hank’s gaze:

MacLaren only reveals the presence of the Cousins at the last possible moment, cutting to one of them just before he opens fire at Hank from behind his SUV. Hank takes him out by gunning into reverse, gets his gun, but runs out of bullets shooting the second Cousin (who is wearing a bulletproof vest), who then cuts Hank down, and then decides to finish him with his shiny, shiny ax. However, the Cousin dropped a single cartridge with a serrated bullet when he reloaded, and now Hank has the smallest chance. (The careful plotting of Breaking Bad is extraordinary, and extraordinarily necessary here. All these details–the vest, the ax as weapon of choice, the bullet in the pocket–have been laid in place in this or previous episodes.)

The first half of the scene is from Hank’s perspective; since the approach of the second Cousin, MacLaren has cut between his perspective and Hank’s. Now she goes into a classic use of crosscutting, between Hank on the ground and the Cousin getting his ax and coming back to kill Hank. The Beat the Clock element comes into play here, as Hank tries to pick up the cartridge and load it, covered in blood and having lost most of his motor function. (It’s another basic rule that too few storytellers understand: it’s the character’s weakness that’s compelling, not the strength.) MacLaren uses a device here that’s often overused, but which is exactly right for this moment: the internal edit, cutting out brief moments in time while the camera doesn’t change position, so we see (for example) Hank fumbling the cartridge, then the cartridge on the ground, with no shot in between of it dropping. This has two effects: it gives us a sense of Hank’s disorientation, and it also jumps us forward in time, reminding us of the Cousin still on his way to kill Hank, jumping us closer to the moment when he’ll arrive.

The underlying tempo of the entire scene has been moderato, and MacLaren marks that time in multiple ways, visually, musically, and sonically: the rhythm of the cuts, but also the underlying throb of Dave Porter’s score and, in the second half of the scene, the honking of a car alarm and the scrrrrrrrape of the axhead dragging along the ground. Even the movements of the Cousin are slower than necessary. Again, many if not most contemporary directors would have shot this scene with dozens of quick cuts; MacLaren withholds those until the very end. The Cousin raises the ax, and then she abruptly finishes the sequence with four quick cuts: slide of gun goes forward (chambering the round)/Hank aims/Hank fires/Cousin’s head blows up. The pace that was so relentless throughout, seeming to walk forward to Hank’s inevitable death, suddenly yanks us forward into that last shot. It was an accident that MacLaren wisely kept that the special-effects brains splattered the camera lens; it’s become one of Breaking Bad’s most indelible images of ownage.

Following the strategy of withholding information to generate suspense, and also following the slow/fast rhythm, MacLaren concludes this sequence with its only omniscent shot, high above and to one side of the action. She holds that long enough for us to see the entire battlefield of the parking lot, and all the bodies left in the aftermath. It’s an entirely static shot (now the only sound is the car alarm) and one of the most classical ways to end an action sequence.

“Salud”

In “Salud,” MacLaren plays Beat the Clock with a twist: we don’t know that a clock is running. Here, Gus Fring (Giancarlo Esposito) tries to take out an entire cartel (and take revenge) all at once. This entire episode burns like a fuse to this scene, without ever revealing Fring’s plan. MacLaren and writers Peter Gould and Gennifer Hutchinson throw some crucial cues at the beginning of it: Mike the Fixer (a legendary performance by Jonathan Banks) tells Jesse (Aaron Paul) “I promise you this, either we’re all going home or none of us are” and we see Gus looking at the pool where his (quite possibly) lover was shot dead by Don Eladio decades earlier. (Again, the plotting carefully layers in the details in previous episodes.) We also see Fring take a pill, but we don’t yet know why (or if) that’s significant.

Again, unlike a lot of contemporary directors, MacLaren understands the importance of clarity and simplicity in action scenes. This scene depends on little details that we’re going to put together at the end, and those details won’t land if we’re overwhelmed by them. My great fear for MacLaren’s direction of Wonder Woman is that the requirements of the Marvel Cinematic Universe Summer Blockbuster™ will clutter up the frame and the action. I suspect she’ll find a way to deal with all that.

Fring moves into the next part of the plan: getting the entire cartel to share an expensive and poisoned tequila. It’s to everyone’s credit that Don Eladio suspects this, and carefully lets Fring drink first; nothing sinks an action sequence more often than one side suffering a sudden case of the stupids. (Steven Bauer as Eladio is one of Breaking Bad’s great guest performances; he makes Eladio the only damn character in the entire series who actively enjoys power.) At this point, MacLaren has given us really only one clue, and no sense that the clock is now running for everyone. The pacing of editing and action is languid, calm, with cuts between close shots and wide shots coming at a slow, regular rate; MacLaren hasn’t even told us this is an action sequence yet.

Fring goes to a bathroom (another quick clue: a shot of Mike watching him head off), and MacLaren and Esposito do a wonderful character beat here. Although action sequences work because of pacing and suspense and, well, action, it always helps to reveal or reinforce some character here. Even with the poison going into his system, Fring still takes a moment to take off his jacket and put down a towel to protect his pants before making himself throw up. Now the act of taking the pill, in retrospect, becomes more important, and sets up the next shot. MacLaren cuts to the poolside and shoots Don Eladio from below, in slow motion, as his nervous system begins to fail and he drops his cigar. (Don Eladio has been mostly shot from below for the whole sequence, with Fring shot at eye level, making Fring look like the smaller, weaker one. That’s just what Eladio thinks.) The shot from below makes him literally  monumental; the image is that of a statue about to fall. It functions both as a symbol for what’s about to happen and a signal that Shit Just Got Real. (Vince Gilligan couldn’t possibly have had the image and idea of Walt falling to the ground in “Ozymandias”; that would be two years in the future. Or did he?)

monumental; the image is that of a statue about to fall. It functions both as a symbol for what’s about to happen and a signal that Shit Just Got Real. (Vince Gilligan couldn’t possibly have had the image and idea of Walt falling to the ground in “Ozymandias”; that would be two years in the future. Or did he?)

MacLaren now moves to a wide shot. Because of the pause, we now have enough information, and enough time, to figure out what’s going on. (The ability to craft a sequence to the maximum intensity that we can perceive, rather than the maximum intensity that’s technologically possible, is a skill that MacLaren shares with Kathryn Bigelow.) Now the wide shot of cartel members collapsing makes sense, and it also catches a quick shot of Mike garroting a guard. MacLaren gives a quick beat of humor here, too, cutting back to outside the bathroom and a shot of someone unconscious outside of it, and Fring oh-so-fastidiously stepping over him. She follows that by tracking Fring walking out, staying on his back, symmetrical in the frame; now he looks absolutely in command.

Like John Woo, MacLaren employs the fast/slow pacing not only between scenes, but within scenes. As the cartel goes down, she gives us a longer moment as Eladio falls facefirst into the pool, and we see him from below. (By now, shooting things from below is a MacLaren and Breaking Bad trademark.) Then the scene jumps in pace again, as Fring suffers the first hit of the poison and then a gunfight breaks out. MacLaren moves to her fastest edits yet, a barrage of internal cuts on Jesse returning fire, deliberately modeled on the first-person-shooter videogames we’ve seen him play. Mike gets hit, Fring is poisoned, and Jesse drives off to finish the episode, one of the strongest cliffhangers for a show that does so many.

“To’hajiilee”

MacLaren’s most expansive and daring use of time comes in her final episode, “To’hajiilee.” In addition to having to coordinate a large-scale shootout, she had the additional constraint of having to set up the next episode, “Ozymandias”; her sequence had to end with the characters in specific places to set up what happened next. (With one minor but noticeable exception, the two episodes flow seamlessly.) “To’hajiilee” has, of course, drawn lots of comparisons to Sergio Leone’s movies, with its slow build to the outbreak of gunfire, but MacLaren goes way past that. Many times, the key to filming a good shootout is to do a good job filming the build-up, but MacLaren actually sets up this scene–and begins manipulating time–over fifteen minutes earlier.

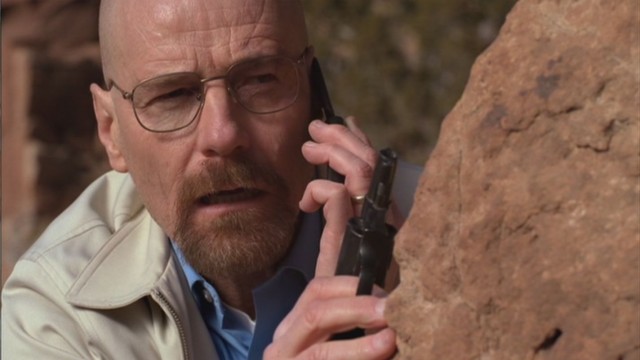

The sequence begins with Walt (Bryan Cranston) receiving a picture message from Jesse–a staged shot of his money, buried at To’hajiilee, actually some of Jesse’s money buried in Hank’s back yard. MacLaren quickly dollies in on Walter’s face, reacting to the picture, another Shit Just Got Real moment. Walter sprints to his car and calls Jesse and starts driving. During this sequence, MacLaren keeps the conversation between Walt and Jesse (and later just Walt talking) going continuously, while cutting between shots of Walt in the car, and exterior shots of the car moving. The conversation is continuous, but the driving is not, and that’s necessary for what happens next. MacLaren creates the illusion that the drive takes place in real time; even though we keep seeing the car get farther out of the city at every cut, the conversation has no pauses or jumps. MacLaren makes the drive to To’hajiilee seem shorter than it could be.

That sets up the second half, as Walter arrives to an empty desert, realizes he’s been tricked, calls in Uncle Jack (Michael Bowen, an often unheralded character actor, in his best performance) and his Aryan Brotherhood associates to come get him, then tries to call them off when he sees Jesse with Steve Gomez (Steven Michael Quezada) and Hank. Now we have another Beat the Clock scene; we know Jack is on his way with reinforcements, guns, and vests (MacLaren shows all of that), and they’re coming to protect their investment in Walt, not to rescue him, so Walt trying to call them off won’t work. We have also established, visually, that there is only one way into our out of this canyon; whoever arrives later boxes in whoever arrived earlier.

MacLaren created the illusion of real time in the driving sequence; here she actually films in real time, and it’s excruciating to watch. Hank arrests Walt, and that takes several discrete steps. At the commercial break, Walt is hidden from Hank behind a rock as Hank calls to him. (MacLaren even includes some establishing shots to slow the action further.) After, we go through several steps: Walt emerges from cover, drops his gun, comes to Hank, turns around, puts his hands over his head, each step called out by Hank to slow things down even more. We can see all the ground Walt has to cover, and we literally see every step, and with every step we’re thinking AAAAAAAAA JACK IS ON THE WAY HURRY UP HURRY UP. (Some of us were in fact yelling that at the screen.)

At no point does MacLaren cut away to Jack en route, which is insanely effective for three reasons. First, it would be redundant, because we already know they’re coming. Second, a cut away from the action here would break the real-time pace of this scene; it would give us relief. Third, cutting to them would give us information that was at best useless and at worst distracting. The intensity of the scene depends on us not knowing when they could get to To’hajiilee; they’re the bomb under the seat in Hitchcock’s definition of suspense. Since we don’t know where they started from, we don’t know when they’ll arrive, and unless we cut to a sign saying TO’HAJIILEE 1 MILE a cut won’t tell us that. Knowing where they are can only lessen the suspense. It’s the kind of simple and unconventional decision that marks a great artist.

When Jack arrives with all the men with guns, MacLaren shifts into her most Leonean mode, using slow motion to stall things before everyone opens fire. What makes that moment work, though, is all she has already done to manipulate our sense of time before we got to this moment. It’s another thing that marks her as a great artist, and as so different from contemporary action filmmakers. So many action films are now conceived in terms of big setpieces, and to the extent there is any plot, character, or filmmaking, it’s simply to get us from one setpiece to the next. MacLaren, along with John Woo, Walter Hill, and Kathryn Bigelow, gives just as much attention to the moments between the setpieces. She’s a great filmmaker.