If perchance you stopped in your local movie theatre to watch a matinee showing of Clint Eastwood’s new film Sully, based on the exploits of aviation hero Sully Sullenberger, who saved the lives of 155 airline passengers in 2009, you might have seen the trailer for Peter Berg’s soon-to-be-released disaster picture Deepwater Horizon, based on the 2010 BP oil tanker explosion which claimed the lives of 11 people and countless animals. And if you liked Deepwater Horizon enough, you must just be excited for Berg’s Patriots Day, which is released to theatres across the country this Christmas, telling the true story of the bombing attack that was inflicted on 2013’s Boston Marathon.

Starting to sense a pattern?

Hollywood has always looked to real events as fodder for their vasty storytelling engines — hell, even the original Birth of a Nation tried to claim historical pedigree for its grotesque white supremacist fantasies — but this is different; at least, more specific. These stories are not just inspiring “human interest” oddities, birth-death biopics of iconic figures, or adapted from stories that occurred many decades ago.

These are movies that are based around events recent events, new stories; these are stories that you probably heard round-the-clock news about, and they’re usually some traumatic event. They’re real life disasters, crashes, terrorist attacks, hijackings, and more. And this is relatively new, at least at this scale (made-for-TV quickies are their own ballgame). Hollywood may have done based-on-a-true-story movies since the beginning, but they didn’t do “Cuban Missile Crisis: The Motion Picture” just a few years after the actual Cuban Missile Crisis.

So far as I can tell, this trend started in earnest around 2006 — exactly a decade ago, with the near-concurrent release of Paul Greengrass’s United 93 and Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center, both of which told, from limited points-of-view, the story of the September 11th terrorist attacks. Greengrass’s film showed the perspectives of passengers and terrorists alike on the doomed United Airlines Flight 93, which was reclaimed from hijackers and prevented from crashing into Washington D.C., but sadly claimed the lives of all onboard. World Trade Center takes on the stories of the handful of police officers who were trapped under the wreckage of the destroyed World Trade Centers yet managed to survive. These films were laser-focused in their setting and perspective, putting the viewers in the perspective of those individuals, alive and dead, who were directly touched by the tragedy. The world famous images of shattered glass and steel, the smoke and flame, 20th century architectural marvel transformed to ruin and ash, the first responders clinging to rubble, the planes waylaid and reduced to waste — all of these images were now taken away from the newspaper pages and the cable news broadcasts, and were instead burned onto celluloid and given over to audiences who believed themselves already familiar with them.

This pattern, or “trend,” if it can be called that, took some years to form, before accelerating rapidly.

Films like Fair Game or Zero Dark Thirty or Lone Survivor took limited aspects and small incidents of the Bush Administration’s quixotic “War on Terror” and attempted to use them as either microcosms of the whole war, or as simple moral parables, with a mixed record of success. The most instantly-iconic of the three, Zero Dark Thirty, staged a bold climax that placed audiences directly in the shoes of the Navy SEAL operatives who, in 2011, raided the Osama Bin Laden complex and killed the Al Qaeda terrorist leader; the sequence’s green-tinted night vision cinematography avoided traditional Hollywood gloss in favor of a pretense towards realism.

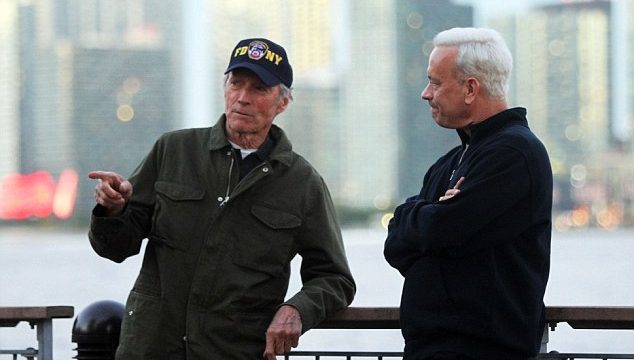

Like this year’s Sully, 2013’s Captain Phillips (directed by United 93‘s Paul Greengrass) made Tom Hanks the captain of a vessel that ran into some bad luck. Hanks’s Captain Richard Phillips struggles against both Somali pirates and his own judgment when his freighter is hijacked, and he’s taken hostage. With a much bloodier and more traumatizing climax than Sully (where everything pretty much works out for the best for everyone), Captain Phillips wrung maximum drama and tension out of the collision between two worlds — one of privilege, another of poverty — a collision that briefly captured the world’s attention for a few days in 2009, when a mild Massachusetts merchant marine became the subject of an international incident.

In this year alone, we’ve seen or will see four major Hollywood takes on recent news stories — the aforementioned films Sully, Deepwater Horizon, Patriots Day, and Michael Bay’s Benghazi-as-action-movie 13 Hours.

So what does this all mean?

As we move deeper and deeper into the age of smartphones, texting, Twitter, YouTube, and social media of all sorts, our conception of “media” becomes more and more diffuse. The September 11 attacks were perhaps the first world-shaking news event of the cell phone era, and since then, the individual’s level of control of a “news event” has become greater; to the extent that major newspapers are now laying off staff photographers, with the idea that the average joe on the street will inevitably snap a quick picture of any newsworthy event, which the newspaper can thereafter utilize free of charge.

This phenomenon, combined with the increasing availability of alternatives to theatrical movies, seems to have created an anxiety within Hollywood and the filmmaker class, a desire to reclaim the news for the media-makers, and away from the one man or woman with a camera phone and a social media presence. “Yes,” Hollywood seems to be saying, “you can see Sully Sullenberger’s plane on Twitter, but you can’t see inside his cabin unless you come to our movie.”

And for the most part, this has seemed to work; many of these films are box office bonanzas, especially for adult-focused dramas, and the Oscar voters have not been sleeping on them, either. For now at least, the movies will stake out their claim on these traumatic events and bad news headlines, and we will consume them. For now, that’s what we will do. But, of course, our futures are as-yet unwritten, and as these films (and the news) can show, life has a way of blind-siding you.