We likely all know this film’s iconic, bizarre, tone-setting nightmare of an opening: Henry Spencer (Jack Nance) floating in space, superimposed, with a look of quiet terror on his face, before floating away as we dolly in on a distant planet. We cut to a God’s-eye view of the cratered landscape, widening into a yonic divide, a void, and encased within is a tin shack where a Man (Jack Fisk) twitches before pulling levers that seem to manipulate and pull out of Henry spermatozoa that shoot away out of sight, to be dropped into also-yonic puddles, before we pan to and dolly in on a bright light emerging from out of the inky black. This bizarre opening, languid in pace with long, uncomfortable takes, serves as a kind of microcosm of the film as a whole, as many film openings have in the past. And it also serves as an illustration of Henry’s inner state: a kind of void onto which various sounds and devices insert themselves to control Henry. And yet there’s light ahead.

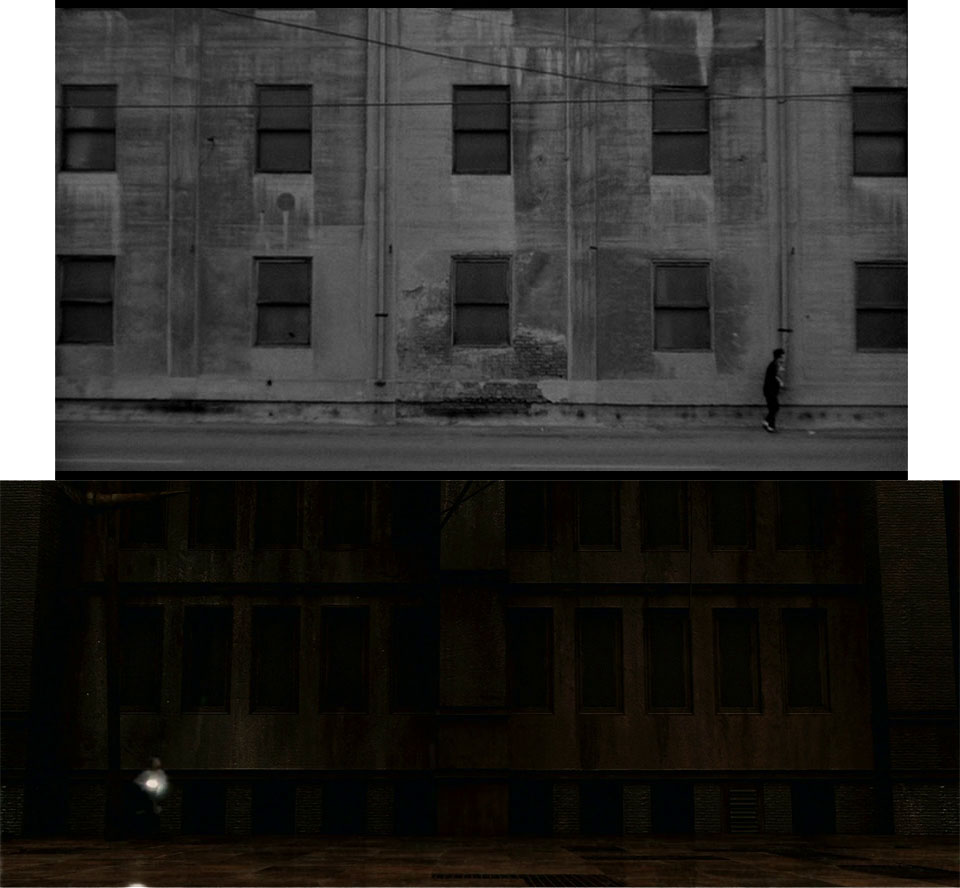

After this we’re planted into the industrial wasteland that is Henry’s home, a world constantly humming with industrial activity and noise, and where far off, comforting organ music faintly billows on the wind. Henry is a small man in this landscape, particularly in a shot that I swear is quoted in the execrable, though beautifully designed and shot, Silent Hill. This world is Henry’s primary state for a good period of the film: comfort, enjoyment, security and warmth are almost always elsewhere and inaccessible, permitted to others but not to him. Henry can’t even catch a break walking home as he steps by accident into a puddle, soaking his foot.

Henry could be said to be up against a brick wall, in both a figurative sense and literal one. His apartment window looks out directly onto a brick wall that prevents any viewpoint on the outside. His neighbor (Judith Roberts) seems interested in him, but Henry cannot attempt any reciprocation. He goes to his girlfriend’s home (presumably ex-girlfriend, or should I say X girlfriend?) because she called, even though he is uncomfortable there, because he simply cannot make himself choose otherwise. Nor can he salvage his relationship to Mary X (Charlotte Stewart) or her family, even as her father (Allen Joseph) attempts to lighten the mood and bridge the gap. It’s already ruined the moment he walks in the door, as the sounds of suckling puppies threatens to overwhelm the conversation. Even the environment seems motivated to drown out any attempt at real personal connection: as Mr. X rants about his legs, the industrial noise outside picks up, only subsiding when Mrs. X (Jeanne Bates, who reappears infamous as one half of the elderly couple in Mulholland Dr.) rushes him into the kitchen. It isn’t long before we learn about what perceptive, intuitive viewers already know is coming: there’s a baby (or something worse) at the hospital, and Henry’s the father.

Baby and Industry as Barriers to Enjoyment

The baby itself is an obvious impediment to the fledgling married couple from the moment it arrives in the film. It is almost immobile, and quickly demonstrates its stubbornness as Mary tries to feed it. It also strongly resembles the sperm-like objects that reoccur throughout the film. Meanwhile, Henry comes home to find a strange little appendage object in his mailbox, which he sneaks into the apartment to hide later. It makes an odd droning noise, and Henry almost seems to take some kind of comfort in it, a sort of private life in a world with no respect for such things with its relentless, penetrating noise. He hides it in the cupboard the night Mary leaves him, unable to bear the baby’s relentless crying, and it is now Henry that must alone handle their child.

At some point in the night, Henry takes the baby’s temperature. Examining the thermometer, he heads away from the baby as though he may put the thermometer away for the night. The light droning noise can be heard, from the cupboard, a reminder of something enjoyed elsewhere out of sight. But as Henry turns around, the shocking sight of a suddenly fevered baby jolts us. Henry will have no private enjoyment that night.

The baby, from here on out, becomes an obvious barrier to Henry’s attempts at finding enjoyment. Even after recovering, when Henry examines the appendage in the cupboard and flashes back to the mailbox, to the possibility of perhaps more enjoyment, the baby cries relentlessly as he attempts to leave his apartment. Henry is trapped here by the baby, and so tries to find escape elsewhere: in the warm radiator, where the Lady in the Radiator (Laurel Near) shuffles along the stage. She strongly resembles Mary, but is more rounded and thick in figure, which include her exaggeratedly distended cheeks. She tries to ignore the sperm-like objects that drop to the stage, then squishes them underfoot, before being pulled into the darkness as if sucked by a mighty wind away from Henry. Not long afterwards do these sperm-like objects reappear in Henry’s bed, as he seems to pull them from out of his suddenly-reappeared (as though emerging from a womb) wife and throw them against the wall. Nothing Henry can do will rid him of these things, and then the appendage leaves him as well, becoming a swallowing void wherein Henry continues to be eluded by the enjoyment he seeks. The baby threatens to overwhelm his seduction by the neighbor woman; she becomes afraid of Henry as she sees the baby-shaped planet from the film’s opening; the Lady in the Radiator reappears, singing about Heaven, and beckons to Henry, but he cannot join her and she is replaced by the Man in the Planet. Henry, thoroughly emasculated, takes his place behind an area of the stage resembling the bedframe of his apartment, and his head is violently popped off by a phallus. The baby takes over, crying relentlessly as a tree is wheeled out onto the stage to bleed, and Henry’s head becomes overwhelmed in the black blood and is transported to a street somewhere. Here, Henry is again so thoroughly emasculated that he is subsumed, this time by the industrial process itself, the production of goods for profit, and the link between the baby and the industrial hellhole is made apparent as pencil erasers are produced from Henry’s brain.

In the world Henry Spencer inhabits, his enjoyment has been lost to others, inaccessible due to the demands of his job, his environment, his girlfriend and society, and most of all his baby. And one senses he realizes this upon waking, vacantly stroking the bedframe before looking outside and seeing for the first time a view of the street, where two men fight one another. The baby becomes overtly menacing, much like the violent streets outdoors, laughing mockingly at Henry. The neighbor woman returns home with another man (quite an ugly man, too), and when she sees Henry, she sees only the baby – Henry is now more baby than Henry, the two have become so synonymous that Henry has no identity anymore without it. And that is why he destroys it.

The link between baby and industry is only made more apparent in Henry’s act of infanticide. As the baby dies, sparks fly out of the wall outlet, and the lights flicker. The baby’s neck extends, recalling the sperm-like objects that Henry sought to be rid of, before its head grows enormous in size – again, recalling the planet of the film’s opening, which we see explode. The Man in the Planet we see again, struggling at the levers that malfunction and spark, before suddenly a white void overwhelms the screen. It’s blinding; out of it comes the Lady in the Radiator, to finally embrace Henry, a figure of warmth and security that now encompasses and envelopes all of Henry’s surroundings. Whether this lasts we cannot know; the film cuts to black, then rolls credits.

The Sound of Enjoyment

Enjoyment is everywhere in Eraserhead except where it counts: with Henry. He gets close to it at times, but it is usually far away and inaccessible, or close by yet fleeting. Organ music appears often in the film, at first when Henry walks home at the film’s beginning, drifting along quietly and almost buried by industrial noise. It reoccurs in Henry’s apartment, but only for the length of a record; then again in the radiator, as the Lady there dances and sings. Its final appearance, though, brings it back to inaccessibility – it plays outside of Henry’s apartment, painfully so, as others take in enjoyment that Henry cannot have. The other noise of enjoyment is the droning most associated with the odd little appendage, though that isn’t its actual first appearance in the soundtrack. This droning first appears with Mrs. X’s attempts at seduction of Henry as she asks him if he and Mary had sexual intercourse – she partakes of enjoyment at Henry’s expense, as if attempting to live vicariously through her daughter’s boyfriend. It reappears with Henry’s secret piece of mail, the appendage, a private enjoyment he hides away from things but is soon lost forever as it becomes a void. The droning’s final appearance, then, shortly follows the organ music’s final appearance: it is when the neighbor sees Henry as his baby. This form of private enjoyment becomes enormously public in this instance, and it isn’t Henry’s enjoyment anymore – it is the enjoyment of his baby, at the expense of its father, as it insists and demands and makes noise.

– – –

It is certainly worth watching Eraserhead with a good set of speakers, or a good pair of headphones. The film’s high contrast black and white are certainly key to the film’s atmosphere and mood, but it is also the sound, the quiet, unnerving sounds that underly so much of the film, that are perhaps most essential to understanding – as much as one ever can – Eraserhead. So grab a pair of headphones, or crank up the volume on your sound system, and prepare yourself for the helpless nightmare that this film is.