With its graphic language (resulting in an obscenity charge in Georgia that was overruled by the U.S. Supreme Court), Carnal Knowledge (1971) expands the conceptual vocabulary for bad love. The eminently quotable dialogue, that, in particular, finds memorable uses for allusions to castration, breaks ground in conveying sexual obsession and frustration.

What the film, however, also does is to shatter the myth of what our esteemed commentator, Son of Griff, calls “the uptight middle class.” To experience the deep-seated angst of Jonathan, a lawyer, and Sandy, a doctor, we go behind closed doors, the camera tracking through apartment hallways and bedrooms, and eavesdrop on conversations of a very private nature indeed.

The director, Mike Nichols, insists on a naturalistic presentation of failed and failing relationships, preserving any number of honestly open moments. As Jonathan, Jack Nicholson explores every micro-dimension of his character’s limited emotional range, narrowed down, with very few exceptions, to anger and fear. The film focuses, especially in the latter sequences, on Jonathan’s sexual decline.

The role of Sandy is played by Art Garfunkel, here a second banana to Nicholson, just like he was, musically, to Paul Simon. Garfunkel has the grating tendency of speaking like he sings, in a breathy high register that often sounds whiny. It makes his character only marginally less unattractive than Nicholson’s.

Carnal Knowledge starts with Jonathan and Sandy as roommates at Amherst in the late 40s. We see Jonathan’s corrupted state in its early formulation. He contrives to date, and sleep with, Sandy’s brainy girlfriend, Susan, who goes to Smith. Jonathan succeeds to the degree he does because he is ruthless enough to push Susan further faster than he knows Sandy would.

Carnal Knowledge starts with Jonathan and Sandy as roommates at Amherst in the late 40s. We see Jonathan’s corrupted state in its early formulation. He contrives to date, and sleep with, Sandy’s brainy girlfriend, Susan, who goes to Smith. Jonathan succeeds to the degree he does because he is ruthless enough to push Susan further faster than he knows Sandy would.

This does not, however, make Susan a bad person; on the contrary, her decisions (her deliberation in making them and their consequences) are what give the plot a semblance of forward motion. After enduring Jonathan’s heavy-handed sarcasm during their breakup phone call, she seems ready to get on with her life.

If viewers can get used to the leaden pace, they will find a few telling clues as to the outcome of Jonathan and Sandy. We realize that Jonathan did not miss out on finding his true love in Susan—he’d always have resented her refusal to play the kind of mind games he seems to enjoy—and that, predictably, Susan chooses Sandy.

After the college years, the plot shifts to the early 60s and, thankfully, picks up speed. Sandy talks to Jonathan about his marriage to Susan. Sandy’s dimness (how he never found out about Jonathan’s betrayal remains a mystery) has contributed to an unimaginative home life. He sounds bored, which gives Jonathan a chance to complain, in a sheer act of psychic projection, about how women are quick to judge him. This, from a guy whose idea of a perfect woman starts and ends with her breast size (Jonathan repeatedly states his preference for big ones).

Even though Jonathan is becoming financially successful in his career, something is dreadfully amiss. What’s happened, he confides to Sandy, is that the pressures of performing in bed have caused him to become impotent.

It’s only when Jonathan meets his dream woman, Bobbie, that he feels cured. The problem is that Jonathan, like Sandy, has unimaginative desires–and Bobbie is exactly what he deserves, a woman who has cultivated the art of masochism.

Like Susan, Bobbie comes off as a sympathetic character. Played by Ann Margret (nominated for best supporting actress for the role), she is fiercely committed to the status quo. She tries to do everything traditionally expected of her, with a man of high social rank, no less, yet feels frustrated with her life.

In some of the bleakly funniest scenes you’re bound to see in any relationship movie, Jonathan and Bobbie tear each other apart. Jonathan, forgetting that he convinced her to become a stay-at-home girlfriend at the start of their relationship, initiates this pointed exchange:

Jonathan: Get a job!

Bobbie: I don’t want a job. I want you.

Jonathan: I’m taken, by me. Get out of the house, do something useful, Goddammit!

In a particularly heated moment, he goes off on a tirade that reveals how much he despises himself for his lack of courage—a far better man would have done the right thing and set Bobbie free.

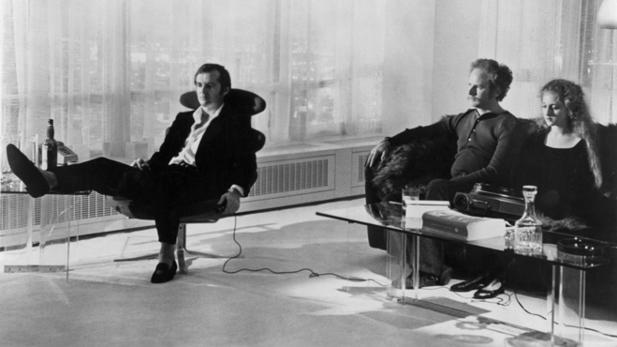

Around this time, Sandy drops by the apartment with Cindy, his new girlfriend. There seems little need for the film to explain how Sandy has blown it with Susan. It’s made clear that he’s become by now more like Jonathan, even praising his choice of a girlfriend (again showing Sandy’s being clueless). Aware that his best friend is as fed up as he is with his sex life, Jonathan proposes swapping partners. It’s another unwise decision, as we soon see.

As sexually aggressive as Jonathan, Cindy zeroes in on his vulnerabilities by insulting both his girlfriend, whom she cruelly calls a “tub of lard,” and his best friend, whom she suggests she can cuckold whenever she pleases—and is open to doing that very thing with Jonathan. In utter disbelief, he watches her walk out the door, then finds Sandy in the bedroom arranging to have Bobbie, who’s overdosed on pills, taken to the ER.

It’s warranted that viewers may find Cindy unlikable; her beating Jonathan at his own game could cause her to appear overly masculine. But the fact that Cindy, Bobbie, and Susan have relatively little to do in the film speaks volumes about the confining roles in which men, like Jonathan and Sandy, have put them. If they somehow become adept at playing these roles, it’s because they’ve found it a social necessity to do so.

And that Cindy and Susan don’t appear at the end of the film, set in the early 70s, suggests they’ve moved on, perhaps having found men who aren’t complete jerks (there, surely, must be a few around, although the film offers little encouragement in that area).

Bobbie shows up as part of Jonathan’s slide-show retrospective of his sex life which he has titled, with appropriately bad taste, “ball-busters on parade.” At some point, they married and had a daughter. Now they’re divorced, and, as he grouses, “She’s killing me with alimony.”

With every slide, Jonathan seems to become a past relic of a bygone era. Yet Sandy looks even more embarrassing, decked out in hippie threads and having taken, as his latest lover, a woman half his age. The future, the film implies, seems no different from the past or present. Even if love is free, those who stand to profit the most are rich, older men.

Therefore, despite the many years Jonathan and Sandy have devoted to acquiring “carnal knowledge,” it turns out that having and maintaining healthy sexual relationships is far more complicated than they could ever begin to understand. In their case, bad love is about the best they could expect.