Films about bad love: what better antidote to the overblown romantic fantasies promoted by Valentine’s Day? Although these films tend to be rarely made by Hollywood, because of their downbeat tone, they often deconstruct the formulaic nature of the love story. For that reason, they are worth watching, even if, for many, if not all, of us, they may bring back unpleasant memories.

Directed by Alan Parker, Shoot the Moon (1982) suggests that maybe the worst kind of love starts out as good love. It’s not coincidental that the wife, Faith Dunlap, tells her husband, George, the reason she’s seeing a younger man is that he reminds her of George when he was younger. Any number of times we observe that people only grow worse with age: not only do people not get rid of their bad habits; these habits become routines upon which they increasingly depend to make sense of the world.

The earlier, presumably better, years we don’t see. We don’t know for certain why Faith and George’s love went bad, but that’s a foregone conclusion—the entire film chronicles the wrenching aftermath. At the start, George, who is a writer, is talking to his girlfriend on the phone, trying to summon the courage to walk out of his marriage. Next, he and Faith attend a book awards ceremony, and he wins. During his acceptance speech, George says all the right things.

The problem, on full display here, is George believes that good intentions are enough—and they usually are in a typical Hollywood film, where things, with the slightest effort, turn out for the best. But Shoot the Moon is not that kind of film. Instead, it spends much time dissecting, with a coldly clinical precision, how George’s gift of speechmaking betrays his actions. Here’s a guy who has the perfect response for any criticism. When Faith accuses him of being angry and violent, he says he’s scared, and then goes on to effusively praise her for keeping the house and family together. You almost have to admire his being such a smooth talker, while having empathy for Faith, who has trouble seeing through his act.

In the role of George, Albert Finney goes to great lengths to show us that, while his character thinks of himself as a fundamentally decent guy, he is in fact a bully who will get what he wants or wreck everyone and everything around him. To deal with conflict, George tends to choose the nuclear option. Given the rather delicate situation he’s in, this can only lead to disaster.

Which it does when George, having already moved out, shows up at the house with a birthday present for Sherry, his older daughter. He’s trying to mend bridges with her, but she’s understandably angry at him. Not only do her and her three younger sisters know pretty much everything that’s going on between their parents; they are present at almost every battle—I can think of only one film, A Woman Under the Influence (1974), written and directed by John Cassavetes, where the kids have such an intense on-screen presence.

Which it does when George, having already moved out, shows up at the house with a birthday present for Sherry, his older daughter. He’s trying to mend bridges with her, but she’s understandably angry at him. Not only do her and her three younger sisters know pretty much everything that’s going on between their parents; they are present at almost every battle—I can think of only one film, A Woman Under the Influence (1974), written and directed by John Cassavetes, where the kids have such an intense on-screen presence.

When Faith tells George repeatedly that Sherry doesn’t want to see him, his pent-up anger explodes. He shatters the glass panel of the door, opens it, and drags Faith outside. After blocking the door so that she can’t get back into the house, he breaks down the bedroom door, grabs Sherry, throws her onto the bed, and starts hitting her on her backside. It takes Sherry’s sisters to intervene before he comes to his senses and realizes his behavior has gone far over the line. He beats a not very dignified retreat from the house, leaving Faith to deal with his shaken children—not to mention her own shaken feelings.

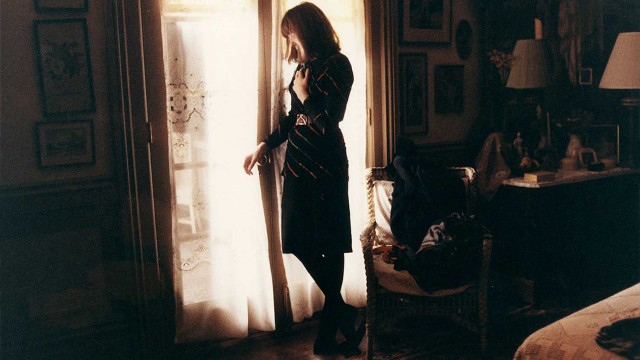

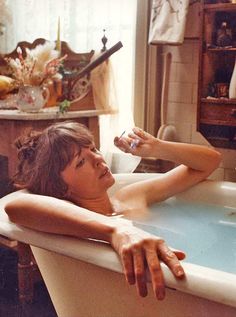

In this light, it would be easy to regard Faith as the victim. Except that’s not how Diane Keaton plays this character. In a spellbinding performance, Keaton brings out how Faith is as clueless as George is, and as willing to settle for the bitter dregs of their marriage as he is. If love has turned him into a monster, it has changed her into a wide-eyed adolescent girl, searching for a man to take care of her.

To deal with George’s walking out, Faith, in a pivotal scene, takes solace by smoking pot in the bathtub. Instead of being able to relax, she sobs like a heartbroken teenager. It takes an actor as talented as Keaton is to pull this off: it looks somewhat ridiculous and yet all too realistic; in an achingly private moment, we see that’s who Faith is.

To deal with George’s walking out, Faith, in a pivotal scene, takes solace by smoking pot in the bathtub. Instead of being able to relax, she sobs like a heartbroken teenager. It takes an actor as talented as Keaton is to pull this off: it looks somewhat ridiculous and yet all too realistic; in an achingly private moment, we see that’s who Faith is.

George and Faith stumble toward a reconciliation, which only deepens the emotional turmoil. Grieving after her father’s funeral, she accepts George’s overtures, and, drunk after a boisterous argument over dinner at a high-class restaurant (that serves unmistakably as foreplay), they have sex in her hotel room.

Sherry discovers them in bed together, and runs off. Faith’s decision to follow George’s philosophy (act impulsively, no matter what the consequences) has to be utterly confusing, if not infuriating, to Sherry, especially when she sees her mother with her boyfriend. This younger man’s heart seems to be in the right place: he picks up on how lonely Faith feels, and tries to reach out to her children. But he is in way over his head.

Despite some shaky, even bizarre moments—the dinner argument coming off as almost a parody of the Hollywood melodrama, the events leading up to the finale have a grim logic. What starts as a laid-back celebration (with the Eagles playing in the background, no less) of a new backyard tennis court and gazebo, built by Faith’s boyfriend, triggers recriminations. Sherry feels uncomfortable and disrupts her mother’s attempts to make a public show of affection with her boyfriend, before running off, as she did before. She ends up at the house where George is having a quiet evening with his girlfriend and her son.

George takes Sherry back to her mother’s place and gets exactly the wrong impression. All he can see is, on the surface, what looks like the satisfaction that he left behind. What he can’t see is what we, of course, can see—perhaps an ironic spin on love being blind: it’s, at best, a momentary happiness for Faith with a guy who hasn’t yet fully discovered the extent of her being damaged. There’s no need to describe what happens next, suffice to say that the wreckage of George and Faith’s marriage becomes presented in a rather literal way, and George brings it on with the same recklessness he displayed earlier in the fight with Sherry.

If, in the closing moment, things are still left up in the air between George and Faith, it only points to the futility of their situation, a stalemate that has required much to be sacrificed, and for little apparent reason or benefit.