Who Shot It: Emmanuel Lubezki. Before he became the cinematographer you hire when you want to shoot something handheld and make it look great, Lubezki’s style was no less distinctive… but it was a completely different style altogether. He began his most lasting cinematic collaboration back in school at Mexico, with Alfonso Cuaron. Together, they worked on several episodes of the Mexican anthology series Hora Marcada, and they made their first feature film together, the unfunny if beautifully-shot sex farce Solo con tu pareja. From there, they made their American debut together, with an episode of the neo-noir anthology series Fallen Angels, with Lubezki also shooting an episode of the series directed by Steven Soderbergh (*cut to: The Narrator orgasming at the thought*), and they made two American films together by the end of the decade; the wonderful A Little Princess and the decently underrated Great Expectations, before creating their three best-known films together in the 2000s; Y tu mama tambien, Children of Men, and Gravity. But their 90s work is completely removed stylistically from those three, with an emphasis on sweeping camera movements and lush lighting schemes. This style of Lubezki’s would be the one he would continue to use for the rest of the 90s, on American films like Twenty Bucks, The Birdcage, Reality Bites (a former entry in the series), A Walk in the Clouds (another former entry in the series), and Sleepy Hollow. But the shift to the 2000s led to the creation of the Lubezki we all know and love, with Rodrigo Garcia’s Things You Can Tell Just By Looking With Her being the first of his films to be shot entirely handheld, with (seemingly) natural lighting. From then on, he applied those skills to the likes of Michael Mann’s Ali, the Coen brothers’ Burn After Reading, and Niels Mueller’s The Assassination of Richard Nixon, taking a break into the middle to shoot two “children’s” films; A Series of Unfortunate Events (which is good, I swear) and The Cat in the Hat (another former entry in the series, which is an abomination unto the Lord) He also formed another major collaboration during this time period, with Terrence Malick, with whom he’s created some of the most jaw-droppingly beautiful images of the 21th century in The New World, The Tree of Life, and To the Wonder (they have two other projects in the pipeline together, one, Knight of Cups, set to be released next spring). Now he’s working with Alejandro González Iñárritu, starting with short-form projects (the wonderful Nike ad “Write the Future” and a segment of the omnibus film To Each His Own Cinema) before making Birdman together and netting Lubezki his second Oscar. It’s a great movie, and fuck y’all, and their second collaboration, The Revenant, will be coming out this Christmas. Also coming soon is Lubezki’s second movie with Rodrigo Garcia, Last Days in the Desert, which promises to feature much stunning location photography as it tells the story of Jesus’s thirty-day-thirty-night fast. And speaking of Jesus, he isn’t in Meet Joe Black.

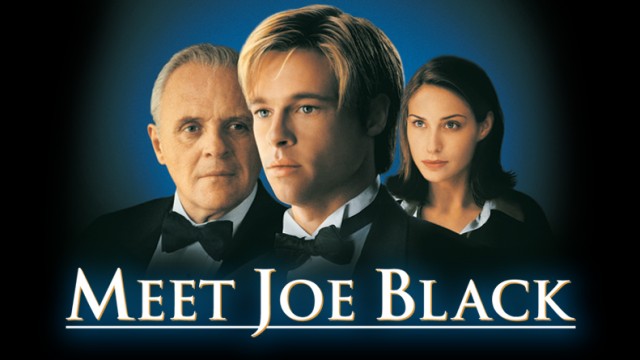

What Do You Mean, Story?: When talking about Meet Joe Black, one must talk about two men. The first man is Brad Pitt. It seems odd to think that there was a time when Brad Pitt was genuinely in danger of becoming another discarded pretty-boy, but it looked like that was what was going to happen in 1997 and 1998. In those years, Pitt headlined a series of films (such as this, Seven Years in Tibet and a future entry, The Devil’s Own) that greatly overestimated the public’s tolerance for Pitt as the stoic, serious guy with pretty hair and eyes. It took Fight Club for Pitt to get back to the live-wire roles everyone wanted from him, and from there he would develop further as an actor. The second man is Martin Brest. Brest wishes he got the second chance Pitt was afforded. After starting by helming acclaimed action-comedies such as Beverly Hills Cop, Going in Style, and Midnight Run, Brest decided in the 90s that he should try making overlong slogs of dramas, with Scent of a Woman succeeding and this not succeeding so much. And then when he hobbled back into making comedies, he made Gigli (another former entry in the series), and his career was over. Certainly Brest has talent to spare, but after the two pieces of garbage he’s subjected me to, I can’t help but take a little pleasure in the fact that he’s been locked out of Hollywood.

I normally save criticisms for after the synopsis paragraph, but I gotta get this out of the way; this movie is three goddamn hours long. Now, I don’t inherently dislike movies that are that long. Hell, I’m probably one of the few people out there who felt the time fly by when watching Christopher Nolan’s last few films. But Meet Joe Black doesn’t earn its running time, to say the very least. I’m probably going to make this movie sound much more entertaining than it is, because you can’t convey in print the feeling of watching scene after scene play at half-speed.

Media tycoon Bill Parrish (Anthony Hopkins) is a few days away from his 65th birthday, and his eldest daughter Allison (Marcia Gay Harden) is planning a lavish birthday party for him (in case you didn’t know his reach, she’s there to remind you by constantly asking if [so-and-so major figure] is coming to his party). Meanwhile, he’s been hearing a voice, his voice, which starts out just saying “Yes” but eventually graduates to having lengthy, if unproductive, conversations with the old man. While this is going on, his younger daughter Susan (Claire Forlani), a doctor, meets a lovely guy (Brad Pitt) at a cafe. They have a nice talk together, but eventually go their separate ways, Susan off into the distance and the guy onto the street, into the hood of a car, upwards, downwards, into the roof of a cab, and upwards and downwards again. This poor schmuck who slipped off the mortal coil by failing to look both ways proves to be a worthy vessel for that voice Bill has been hearing, which turns out to be Death. Death, who eventually goes by the name Joe Black, wants Bill to give him a tour of humanity, in exchange for some more time on Earth. The problem is that Susan recognizes Joe and falls for him. Of course, you can’t structure a movie the length of Robert Altman’s Short Cuts on that, so we get additional subplots which seem to stretch on for longer than Bill is given, including one with a dying woman where Pitt gets to practice his Jamaican accent and a particularly interminable one with Bill’s company, where Susan’s boyfriend (a board member) doesn’t like that Bill said no to a merger, and thinks that Joe is feeding him advice on how to operate the business. Remember, this is less exciting in the film than it sounds described here.

This film is pretty obviously trying to get across a message about life. It’s about Death enjoying the pleasures of living enough that he wants to stay with the living, after all. I’m not saying that a good movie couldn’t be made from that idea, but it would take a quiet touch to make it something less than ham-fisted. And Martin Brest’s fists (and the fists of the film’s four(!!!) writers) are the furthest thing from kosher. There’s so much talk here about how much life is worth living, how beautiful and important love is, how life is precious and shouldn’t be wasted and God and the Bible, and it’s all so sugary and self-important (for fuck’s sake, “What a Wonderful World” plays twice during the ending, because the audience didn’t get the hint the first time) that it would be a drag even if it was fleet on its feet otherwise. Oh god, it definitely isn’t that.

Remember when I said that scene after scene in the movie play at half-speed? I mean it. Every single goddamn scene in this movie goes on too long. Every last one of them. Every scene here is filled to the brim with portentous, unnecessary pauses, with dialogue and dead space that kills whatever impact a revelation or even a joke might have had. If you cut out just that, let alone the deadweight subplots, I’d bet this movie would have half as long and less of an endurance test. Not that it would be turned into a good movie that way. Most of the film’s attempts at jokes fall utterly flat (although, in the interest of fairness, I did chuckle at the running gag-of-sorts about the phrase “death and taxes”), its platitudes about life are just that, platitudes, and the bits with Joe discovering life and that he’s a big fan of peanut butter just lie there and die. But it’s not just the script. Every actor in this film plays their character as if they’re deathly afraid of using their outdoor voice. Anthony Hopkins fares best, I guess, on the basis of his performance being fine, Brad Pitt briefly threatens to be charismatic before spending much of the movie as a wooden bore, Claire Forlani is lovely-looking but a tree, Marcia Gay Harden gets one character trait, Jeffrey Tambor (as her husband) can visibly be seen wishing that Arrested Development wasn’t five years in the future, and Jake Weber, as Susan’s asshole boyfriend and Evil Board Member, two roles that demand serious scenery-chewing separate of each other, let alone together, plays his part with all the tired solemnity of someone at Grandma’s funeral. And lemme tell you, Grandma deserves better than this movie, this airless, dull movie that didn’t even really give me that good of material for this entry. Why couldn’t all of this be Brad Pitt getting creamed by two cars?

Screw That, Let’s Talk Pretty Pictures: These are some mighty pretty pictures indeed. One of the film’s few saving graces is its superb technical aspects, chief among them Emmanuel Lubezki’s cinematography. The lushness that is present in the rest of Lubezki’s 90s work is indeed working at full force here, with a steady stream of light coming in at all times, through windows, from lamps, and sometimes seemingly from nowhere at all (that’s the movies for ya). The complete absence of murkiness or dimness makes sense within the world of the movie, given the opulence of the Parrish house (designed by Dante Ferretti), and it makes sense on a less literal level, the absence of shadows removing any sense of “darkness” from a story about a guy who’s going to keel over any day now. The light also helps make the film look romantic as opposed to just being romantic (although it isn’t romantic, so it just looks romantic), with the light making Pitt’s feathered hair glow and accentuating the beauty of his and Forlani’s bodies and faces. All that said, though, the lush lighting is actually less pervasive than it is in, say, A Walk in the Clouds (which makes sense, given that that film gives itself over completely to the tropes of melodramas) and Reality Bites, creating a look that manages to put it a little close to reality while still not returning reality’s phone calls.

Favorite Shot(s): Brad Pitt gets two great introductions here, one as Guy in Coffee Shop and another as Joe. In both, his face is initially obscured, hidden behind distorted glass, with the movie star reveal of his face coming a little later. In the coffee shop, he’s practically got a halo surrounding him from all the light coming through the windows, but when Joe reveals himself to Parrish in his library, the meeting is a more sinister one, his entire body grossly distorted, with a hint of his feathered hair peeking through, and his voice disguised.

Is It Worth Watching: How about instead of seeing this, you just rewatch this gif?

Stray Observations:

- Thomas Newman’s score for this almost convinced me on several occasions that what I was watching was worth emoting over. Nicely played, Mr. Newman. First you get on my good side with your Soderbergh work, and then you come close to making me care about this piddle.

- Lubezki and Pitt would later reunite to much better results with The Tree of Life and Burn After Reading. I bet Joe Black doesn’t even know what a Schwinn is, let alone think that another kind of bike is a Schwinn.

- As you can see in the gif helpfully linked above, Pitt kinda gets thrown around like a rag doll there. And yet, when Pitt bares his chest in the prelude to a sex scene later in the film, I noticed not a solitary bruise, which seems like the minimum damage that could’ve been inflicted on Pitt in that scenario. Did Death taking over his body mean that all wounds were healed automatically? Are we expected to believe he has a magic chest? Boy, I hope somebody was fired for that blunder.

- You may be asking (you aren’t, but it’s fun to pretend) where this ranks in terms of Lubezki’s work that I’ve covered for this series. Well, if it wasn’t for the cinematic war crime that was The Cat in the Hat, it would be dead-last.

- God, I hope The Revenant kicks as much ass as it looks like it does.

Up Next: Behind every pretentious fraud is a pretentiouser fraud.