(Please note that, due to the paucity of online screenshots for this film, there will be no images in this review.)

Who Shot It: Dick Pope. Perhaps sadly, Pope will likely spend the rest of his life being best-known not for his work, but for the fact that, when his Oscar nomination for Mr. Turner was announced, the announcer said his name as “Dick Poop”. While that may be hilarious, it still overshadows a great body of work. Pope was a contemporary of Roger Deakins, the two going to school together and working together on many of their early projects (Pope’s work can be found in the Deakins-shot 1984, Mountains of the Moon, and The Secret Garden), but whereas Deakins leave the U.K. to conquer America, Pope largely stayed in his homeland, and made his most noteworthy collaboration there. That collaboration is with writer/director Mike Leigh, which began with Life is Sweet in 1990 and has continued to this day, their latest, the aforementioned Mr. Turner, being released in 2014. The films they’ve made together run the gamut from stylistically restrained to crazypants gorgeous, Pope making sure to bring the correct look for each film, even if the results won’t make the audience drool. If Pope’s work ended there, he’d have a career well-spent, but he’s worked on so much more. He’s made two films for Richard Linklater; Bernie and Me and Orson Welles. He shot Honeydripper for great-cinematographers magnet John Sayles. He shot Christopher McQuarrie’s directorial debut The Way of the Gun. He shot something called Angus, Thongs, and Perfect Snogging (incidentally, this film is the one time he was credited as the much less mockable “Richard Pope”). And he won his first Oscar nomination in 2006 for his silent film-inspired cinematography for Neil Burger’s The Illusionist. That same year, he also graced Barry Levinson’s Man of the Year with his presence behind the camera. You know what they say about eating the bear vs. the bear eating you.

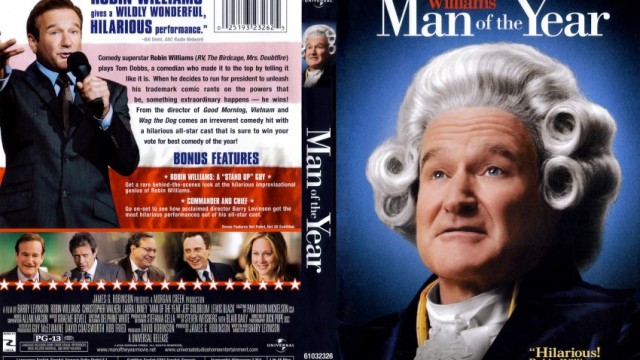

What Do You Mean, Story?: The 2000s were a frustrating time for fans of Robin Williams the actor. It started off well, with a trio of great performances as low-to-high-level psychopaths in 2002. 2004 was marred by him going full-retard in David Duchovny’s House of D, but at least he wasn’t just churning out more family comedies (the same year, he headlined the sci-fi drama The Final Cut). But any hopes that he would be fully entering a new, more mature section of his career were dashed by 2006, which saw the release of Night at the Museum, RV and Man of the Year. The first two was yet more toothless, manic family-comedies (Museum being better at it than RV), and the latter seemed like another in the line of gimmicky high-concept comedy vehicles for him. None of those films were well-received, but RV disappeared into the ether pretty soon after the light of the projector dimmed and nobody could really find it in their hearts to really hate Museum, while Man of the Year ended up providing a more lasting strain of bad, beyond just “lack of trying” and into “what on God’s green Earth were you thinking?”. The “you” in that case wasn’t Williams but writer-director Barry Levinson, who had mostly been firing blanks creatively since Wag the Dog, and his return to that film’s politically minded comedy proved to be bordering on disastrous this time around. But is it all okay, you know the answer to that.

The premise of this film was almost certainly the result of Levinson thinking “What if Jon Stewart was President?”. Of course, hiring Robin Williams in the Jon Stewart role (incidentally, this one of those movies where a character clearly based on a real-life figure exists in the film’s world alongside that real-life figure) instantly turns that premise into “What if Robin Williams had the opportunity to do a lot of manic improvising, and then became President?”. Not that, when he’s on, I can’t enjoy a good bit of Robin Williams manic improv, and I will admit he gets some good lines here as TV pundit Tom Dobbs, but most of his gags are lame, and the overall effect is tiring. But one of his audience members obviously disagrees, as one night, during the pre-taping talk with the audience, she blurts that he should run for President. And a few shows later, whaddya know? He decides to run as an Independent. His platform is, at first, one of straight talking about the issues, no jokes, before his manager (Christopher Walken, giving an honest-to-god performance as opposed to acting weird) and head writer (Lewis Black) convinces him to add a little levity to his act. They manage to get Dobbs a spot on the debate, and he uses his spot to interrogate the other two candidates on their policies with jokes about Grandma wearing American flag thongs. When the election comes, Dobbs is only on the ballot in a select few states. And guess what? He wins all of those states, and the election! Looks like this jokester is gonna take his brand of politically-based dick jokes to the Oval Office!

Eleanor Green (Laura Linney) has uncovered a problem. She works at Delacroy, a software company which has standardized a new method of voting in elections. The problem is about that system; there’s a glitch, which screws up the results and declares the winner based not on the number of votes, but some other, unknown factor (just wait until you hear what that factor is). She is concerned by this, and tells the company’s head about it, and he tells her he’s fixed the problem when he’s done jackshit about it. She believes it’s been fixed until election night, when she notices that the results are strikingly similar to the results under the glitch. When she blabs about this to a coworker, she’s pulled aside and given a talking to by another company official (Jeff Goldblum), whose speech is filled with so much doublespeak and veiled threats that he could make a killing working at the Parallax Corporation. She goes home, obviously troubled, and watches the election results come in, only to be grabbed by a man hiding in her house, who injects her with an unknown substance and leaves her there, passed out. The next morning, the content of the substance is revealed to be almost every drug under the sun, which causes her to be frazzled beyond belief at work, ultimately needing to be hospitalized. She is dismissed from Delacroy, and she elects to become a whistleblower, blowing the whistle to the highest authority she knows; the President-elect who shouldn’t actually be the President, who believes her story. But she’s dogged all along the way by Delacroy’s goons, who break into her motel room, record her phone calls, and hold a press conference deeming her a psychologically damaged drug addict who created the glitch herself. Oh, I almost forgot to mention; the glitch ranks the candidates in alphabetical order of the double letters in their last names, i.e. Mills is ranking behind Kellogg, and Dobbs before both of them. Oh yeah, I almost forgot to mention that too; these two plots are from the same movie.

If you read those synopses, and thought “Wait, how do those two plots exist comfortably within the same movie?”, I’ll give you a hint as to an answer; they most certainly do not. I really don’t know what Levinson was thinking when he wrote this; it’s not like the first premise can’t sustain a movie on its own, you can certainly wring comedy out of the situations Dobbs would have to face in office. And it would be one thing if this movie was a tonally inconsistent mixture of two good movies. Neither of these movies are any good; the comedy in the Williams portion is limp and obvious (even someone with as much a fondness for dumb accents as Stewart wouldn’t deliver jokes this uninspired), and Williams isn’t believable as a megapopular TV pundit, an issues-pushing Presidential candidate, or the President-elect. I guess it’s not a bad thing when the comedy almost entirely disappears in the second half, but it’s still jarring, and what it’s replaced with is completely absurd. Alan Pakula knew how to wring palm-tightening suspense even out of implausible scenarios (god knows the image of someone walking off the Space Needle shouldn’t be as unnerving as it is as Pakula handles it), and Levinson is no Pakula, but this material would defeat even Pakula, as the specifics (the glitch, the fact that the excuse for Eleanor not being able to talk to Dobbs revolves around an electronics store not selling a charger for a cell phone that’s been out for a year) are so comical that there’s no chance in the world it would be taken seriously if it was in the middle of a full-hearted thriller. And then there’s other drama, about Walken being hospitalized and confined to a wheelchair, which is completely and utterly pointless even in this botched stew of a movie. This movie doesn’t know what it wants to be, and nothing it wants to be is anything people would want to see. Where’s David Mamet when you need him?

Screw That, Let’s Talk Pretty Pictures: I’ll give this movie this; Pope does not phone this one in. In fact, he helps provide the one sense of continuity between the “comedic” and “suspenseful” sequences in the film. Much of the film has a very honeyed, warm look, Pope’s way of telling the audience “Hey, I know this is a complete fantasy too”. This is established from the opening scenes at Dobbs’ show, where the green screen behind him is lit very delicately, giving it a glow. All of the sequences with Dobbs are lit this way. But with Eleanor, Pope switches things up. The first time we see her, hard at work at Delacroy, the image is cast in a moody blue tint, suggesting that no good could come from things occurring here. Blue is utilized throughout the film as Delacroy’s color; it’s the shade of the walls in Eleanor’s apartment, it’s the lighting of the parking garage where she’s taken by a Delacroy goon, it’s the snowy ambiance of the night when she’s injured after another goon attempts to run her over. Perhaps knowing the whiplash that would occur without this, Pope and Levinson help guide the viewer through the tones by keeping them on-edge when cool colors show their faces. And aside from colors, Pope’s compositions here are consistently excellent, capturing the barrage of TVs playing Dobbs’ debate performance (this sequence is one of the highlights of the film solely from an aesthetic perspective) and the insane number of people behind Dobbs in lots of wide shots, which may not seem like the most obvious approach for the comedy, but it’s not like the jokes were going to be any funnier (or funny at all) if they were handled in close-ups.

Favorite Shot/Sequence: I can’t say this is really the best sequence in the film aesthetically (again, the debate is probably that). But I can’t help but get a big goofy grin on my face (one of the few grins the film provides) knowing that, with this film, Dick Pope was able to light and shoot the Saturday Night Live Weekend Update set (with Tina Fey and Amy Poehler behind the desk).

Is It Worth Watching: Hahahahaha, that’s funnier than anything in this movie.

Stray Observations:

- I advise you to watch the film’s trailer, however, just to get a sense of how well the film’s political thriller element was marketed.

- Seeing the best incarnation of the Weekend Update duo in this film is not going to help me readjust to the actually-quite-adequate comedy stylings of Che and Jost when SNL comes back.

Up Next: I let the people decide this one. The people let me down, but I’ll still be following their whims.