Who Shot It: Maryse Alberti. Alberti very recently became a favorite of the activist side of Twitter (the Lexi Alexanders and such) for her stunning work on Ryan Coogler’s Creed, not to mention the fact that she’s a female cinematographer (cinematography is a very, very, very, very male field, sadly) who shot a major hit for a black director with a predominantly black cast. But just because it’s taken this long for her to get major recognition doesn’t mean that she’s been toiling in b-projects this whole time. After moving to America from France to see Jimi Hendrix in concert (Hendrix died three years prior to her moving), she eventually moved into film, working primarily in documentaries. Her breakthrough came with Todd Haynes’ debut Poison, which mixed documentary-style aesthetics with extreme artifice (two years later, she shot Haynes’ short Dottie Gets Spanked, which deals exclusively in the latter). After this, she mostly stayed small, continuing to work in documentaries (including two with Michael Apted) and independent films, hitting a second breakthrough of sorts with the former in 1995 and 1996, when Terry Zwigoff’s Crumb and Leon Gast’s When We Were Kings were released (in addition, in 1997, a failed TV pilot she shot for David Frankel won the Oscar for Best Live-Action Short Film). Before you could say “Wait, can someone really have two breakthroughs?”, she had a third breakthrough in 1998, when Haynes’ Velvet Goldmine (a gorgeous-looking stylistic fantasia which gleefully mixes grunge and glitz) and Todd Solondz’s Happiness (a movie whose great look is ignored in favor of everything else about it) were released, and when she became the first contemporary woman to grace the cover of American Cinematographer. But she still pressed on in the years that followed mostly making documentaries (which she very much enjoys making, for their opportunities for lessons and the variety of small tools at her disposal) with the occasional foray into fiction (most notably Richard Linklater’s Tape), working with Martin Scorsese on his Bob Dylan doc No Direction Home, and striking up a very fruitful relationship with Alex Gibney, shooting at least portions of most of his docs. In fact, in the decade before 2015, she shot two fiction films, one the low-profile Stone and the other Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler (so, a bit more high-profile). So it’s surprising that 2015 brought three narrative films (plus some additional photography on Gibney’s Going Clear); Creed, M. Night Shyamalan’s The Visit (which might be the only gorgeous found-footage movie ever), and Freeheld (plus David Frankel’s Collateral Beauty, a studio movie with Will Smith, Edward Norton, Kate Winslet, and Keira Knightley, coming out next year). Guess which one of those I’m covering today (hint: it’s the one you haven’t seen)?

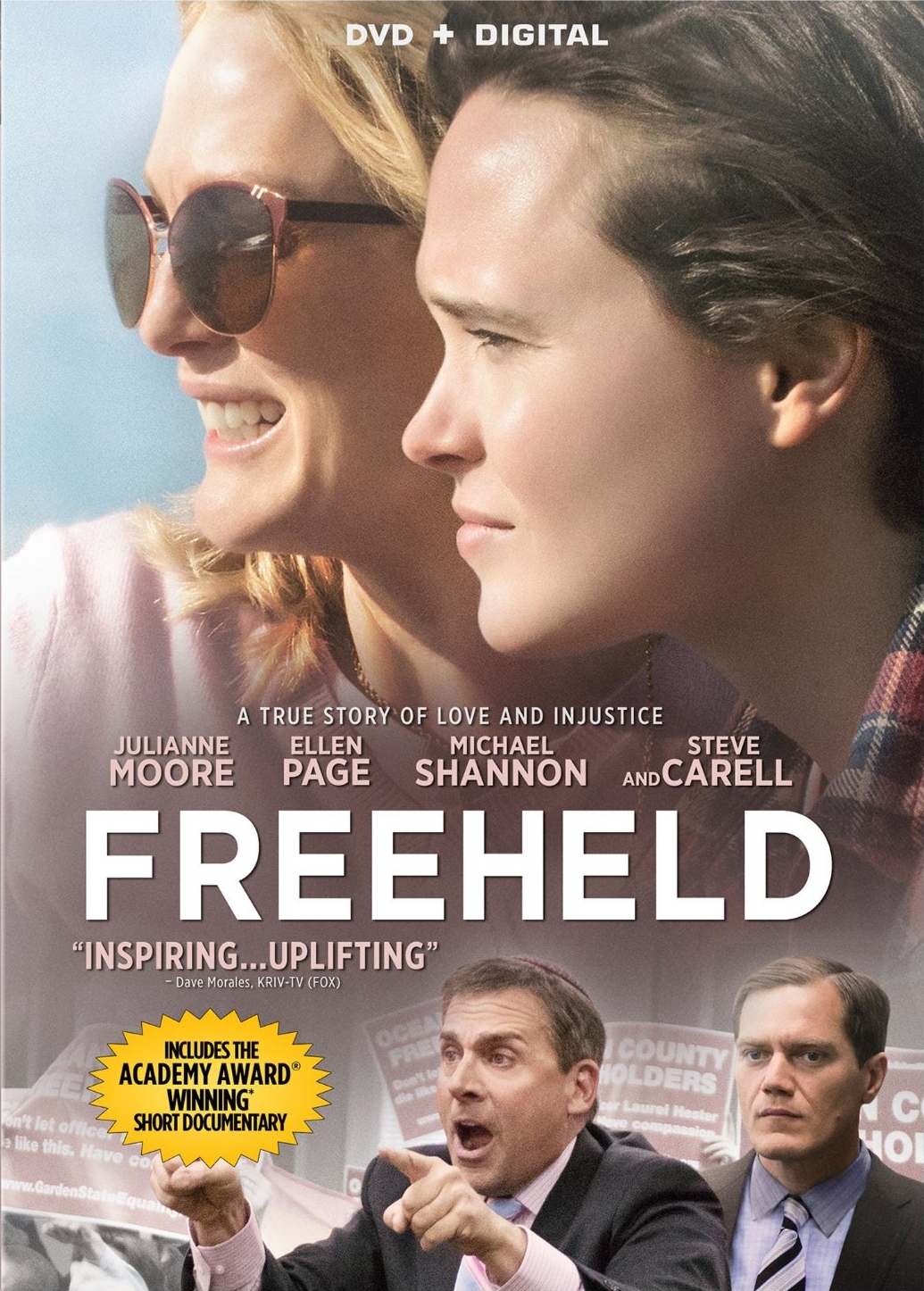

What Do You Mean, Story?: It’s never good to be “the other movie”. It’s never any fun when your hard work is brushed off because something vaguely similar comes out around the same time. And oh boy, I cannot imagine anyone involved with Freeheld was having much fun around its release. It’s a drama about a lesbian couple released in 2015… but not the drama about the lesbian couple released in 2015 that critics liked. It stars Julianne Moore in an Oscar-friendly lead role as someone going through enormous suffering… that happened to premiere after Julianne Moore finally got an Oscar for an Oscar-friendly lead role as someone going through enormous suffering. It co-stars Michael Shannon during what historians will know as the “Jesus fuck, stop making so many movies, Michael Shannon” period, as well as Steve Carell, the year after Foxcatcher and the same year as The Big Short. And it wasn’t even the film shot by Maryse Alberti to get serious Oscar buzz that year! The movie pretty much fell in a hole and died after it got mediocre reviews after its premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, despite having a deeply moving true story at its core. Does that true story shine through in the end, or was something more than timing bungled during the film’s making?

Laurel Hester (Julianne Moore) is a New Jersey police detective, getting the job done with the assistance of her partner Dane Wells (Michael Shannon). They have a nice banter going, kinda like a married couple, and the reason they’re not married becomes clear when Laurel falls for Stacie (Ellen Page), meeting her at a volleyball game in Pennsylvania before hitting it off, even with Laurel’s affiliation with the fuzz (that comes in handy when some dipshit wannabe muggers approach them). Eventually, they move into a house together and get a domestic partnership, eventually having to inform Dane of this (he’s initially angry about Laurel not informing him of this earlier, although he eventually becomes wholeheartedly supportive). It’s not too long after that that Laurel (who, in the film’s early scenes, practically has a cigarette hot-glued onto her fingers) has late-stage lung cancer (I must give props to the filmmakers for not giving Laurel a Cough of Doom to portend her illness). Laurel asks the New Jersey Board of Chosen Freeholders to give her pension to Stacie so she can afford to keep their house. Naturally, given that the makeup of the Freeholders is pretty much a rainbow of the patriarchy (one of them can’t deal with Laurel being a lesbian because “she’s so not like a lesbian”), all but one of them votes to deny Laurel’s request (the Henry Fonda of the group is played by Josh Charles), and the dissenter is eventually bullied into denying it by the other four. Dane suggests that Laurel go to one of the Freeholders’ meetings and make a statement, drumming up the controversy the Freeholders want to avoid. After a reporter takes interest in the story, so does a gay Jewish lawyer named Steven Goldstein (Steve Carell), and with his entrance comes a wave of broad, crowdpleasing jokes (he tells Laurel “I wouldn’t know what to do with your vagina” in response to her asking if his talk about their case in relation to marriage being a proposal) in a movie that had previously elected to not use its outside voice. He says he can make their issue a national story, and shine a light on the issue of marriage equality. Will he convince the Freeholders to reconsider, or will the viewer turn off the movie because of him before they get to that point?

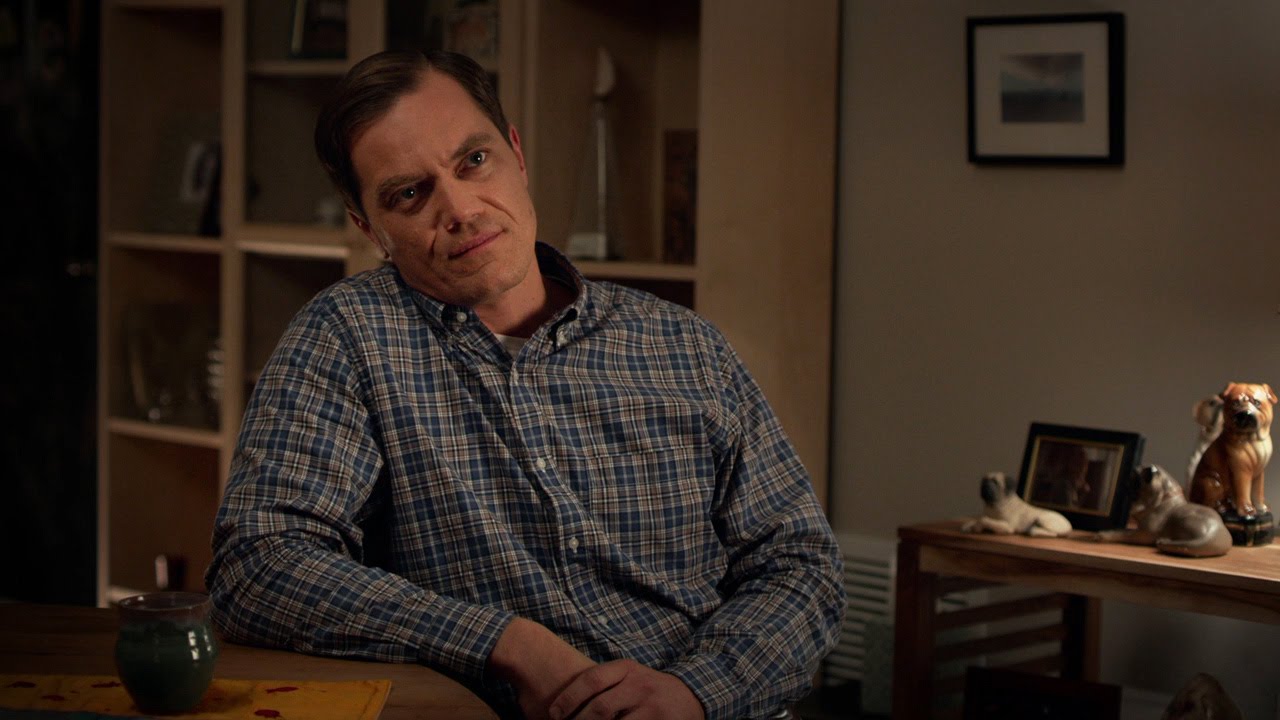

I’d say that this movie’s cast is not the problem, but that’s three-fourths true. Julianne Moore is typically good, as she is in most non-The Lost World: Jurassic Park projects, and she has a very believable, lived-in chemistry with Ellen Page, which is undoubtedly important to the film. I feel bad calling the straight white man in the movie about lesbians the best part, but in this case, Michael Shannon really does give the best performance in the movie, playing Wells as someone whose support for Laurel is movingly unwavering but also quiet (anyone expecting honey-baked Shannon ham should rent Premium Rush instead; his biggest outburst here is maybe a 3 out of 10). But then there’s that other fourth. I liked Steve Carell in The Big Short when others said he was unwatchably broad, but his performance here is a miscalculation of the highest order. I don’t know if the real Steven Goldstein is this big, but even if he can be seen from space, I’m sure he would understand if his demeanor was toned down for a film this muted, because here, Carell’s performance feels like a major supporting turn by the Great Gazoo in the middle of Philadelphia, playing Goldstein like someone at an improv course told to be gay, Jewish, and from New Jersey. Even worse than just being a bad performance, Goldstein pushes Laurel and Stacie out of their own movie, which seems rather remarkably counterintuitive. Although, sadly, Laurel and Stacie’s movie is not as good as it should be. The screenplay (written by Philadelphia screenwriter Ron Nyswaner) is rather weak, not investing Laurel or Stacie with enough character (the most we know about Stacie from this movie is that she’s vaguely good at her job, and Laurel’s big scene showing her at work is a pat “I know what it’s like to be confused” speech) and mostly dutifully following the beats of both injustice movies (at the police station, we get both a closeted gay cop afraid of speaking out and a homophobic cop eventually convinced to do some measure of good for Laurel) and terminal illness movies. This screws over Moore and Page’s good work, not to mention the efforts of the real-life people, from all directions, leaving them symbols for the cause rather than real people who happened to get swept up in the cause, making the inevitable late-film “saying goodbye” scenes less affecting than they should be. The good intentions behind the film are clear, but they end up suffocating what could be an incredibly moving tale.

Screw That, Let’s Talk Pretty Pictures: I’m going to get this out of the way first; this movie is no Creed in terms of aesthetics. It actually reminds me a lot of Julianne Moore’s actual Oscar movie, Still Alice, in terms of its look. Like Still Alice, the film’s cinematography is unflashy, largely using medium shot tableaux along with some judiciously-used close-ups. Also like Still Alice, the cinematography passes beyond “unflashy”, which I have no problem with, into “bland”, which I do have a problem with. I’m not asking the cinematographers to pull an Assassination of Jesse James here, but what I am asking is to utilize lighting in a way beyond “it keeps the actors visible”. For it being handled by someone so talented, there’s not very much artistry in the cinematography here, it having the look of a TV movie more than something headed to theaters (and it should go without saying that there are many recent TV movies that look a lot better than this). I get why this was done, probably as a way to showcase the message as more important than the aesthetics, but when the aesthetics feel this antiseptic, that only ends up distancing the viewer further from the main characters, making them feel like they’re watching this struggle from behind a window pane.

Favorite Shot: That being said, I do really like one shot here. It’s right before the inevitable head-shaving scene, a profile shot of Laurel’s head against a blinds-covered window, the slight glimmers of light shining on the last remnants of Laurel’s hair.

Is It Worth Watching: I wish I could say yes. I really wish I could.

Stray Observations:

- The film’s score is done by Hans Zimmer and Johnny Marr, and it’s refreshingly low on bombast for the possible combination “BWAAAAAMP guy and a gay rights movie” suggests.

- Look at this movie’s DVD cover, and specifically at Michael Shannon’s face on said DVD cover. He reacts for all of us who suffered through Carell’s schtick in this.

Up Next: The best kids underdog movie ever shot by the DoP of Schindler’s List.