Who Shot It: John Toll. Toll’s career as a cinematographer (he had previously done second-unit work and worked as a camera operator for the likes of Conrad Hall, Allen Daviau, John Alonzo, Haskell Wexler, Michael Chapman, and Jordan Cronenweth) took off rather quickly, given that by the time he shot three films that had been widely released in theaters, he was a two-time Academy Award winner. Those two Oscars were for Edward Zwick’s Legends of the Fall and Mel Gibson’s Braveheart (his work on the latter is one of the few parts of the film I can wholeheartedly get behind), and following the epic nature of those two films, Toll would go onto become one of the best cinematographers out there for shooting mid-range-to-big-budget movies. From there, he shot Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line, one of the most gorgeous films of all motherfucking time, the poorly-received Sam Shepard adaptation Simpatico, and two films for Francis Ford Coppola; the well-received The Rainmaker and, uh, Jack. Other than The Last Samurai, his second film for Edward Zwick, after this, he would spend a decade bouncing back and forth between directors without starting new collaborations, working with Ben Affleck (Gone Baby Gone), Ben Stiller (Tropic Thunder, the number-one movie of its summer), George Nolfi (The Adjustment Bureau), Peter Hedges (The Odd Life of Timothy Green, or the one about the plant-boy), and Nancy Meyers (It’s Complicated, which I’ve noticed can be found on the shelves of every used-DVD and Blu-Ray store in existence, a la R.E.M.’s Monster), plus the slightly-obscure likes of Rise: Blood Hunter, Seraphim Falls, and former entry The Burning Plain (which he finished after Robert Elswit, its original DoP, had to leave). After this, he eagerly boarded the Wachowski Starship, shooting their portions of Cloud Atlas, which led to him shooting Jupiter Ascending (which, regardless of what one thinks about it, although the only right answer is that it’s a lot of fun, has some massively purty colors) and the entire first season of Sense8 (where he gets in many beautiful shots of many different locations), his second recent TV gig after shooting the pilot of Breaking Bad. Recently, he’s also shot Iron Man 3 for Shane Black (he may also shoot Black’s upcoming Predator sequel, uh, The Predator) and is currently working on Ang Lee’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, which is being at 120 frames per second(!!!), as well as the second season of Sense8. But today we’ll be looking at his work with Cameron Crowe. They started working together in 2000, when Toll bathed Crowe’s autobiographical Almost Famous in a neverending supply of California sunshine. From there, they worked on Vanilla Sky (which I find thoroughly underrated), where Toll’s work was just as beautiful (maybe moreso) and utilized in a more pointed manner (since the film is spent mostly in the head of a man who thinks his life is wonderful enough to be shot by John Toll). And their collaboration ended with the release of their third film together, Elizabethtown.

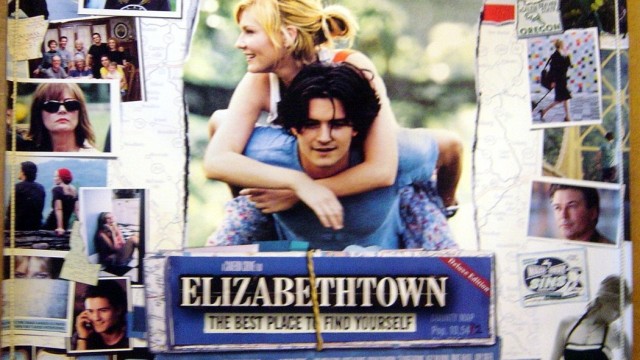

What Do You Mean, Story?: I’ve covered two other films by Cameron Crowe for this series. The first was We Bought a Zoo, and the second was Aloha. However, I feel like I should’ve covered this film first, for the same reason you wouldn’t start reviewing Star Wars movies by covering The Empire Strikes Back; you can’t start a story with the first act missing. We Bought a Zoo saw Crowe reduced to churning what feels like a commodified version of his typical endearing optimism; this was Crowe as a marketing hook for a treacly family movie, not Crowe as an auteur. And Aloha sees Crowe back at the steering wheel only to immediately crash into a tree, get back on the road, drive off a cliff, and drive around the cavern for a little bit before crashing into another tree (I’ll admit I find it endearing in the same way I’d find a dog who keeps running into a brick wall cute; for that reason I’d reach for it ten times out of ten if I was given the choice between it and Zoo). But, well, how did he get here? Technically, Crowe’s critical decline began with Vanilla Sky, but the reviews for that generally didn’t get too much more negative than a “You tried” medal. No, it would be Elizabethtown that would appear to have completely broken Crowe (I wish I could say it sounds like Roadies got him back on track, but alas…). All seemed well for Crowe and the film when it was accepted as a work-in-progress to the Toronto International Film Festival. And then the film was actually screened, prompting a result not unlike a mass exodus from the screening room. The reviews there ranged from your typical scathing notices to outright concern for Crowe’s mental health, and by the time it made it to American theaters, it was absent 18 minutes of material that was present at Toronto. But that did little for it in the long run; reviews were still awful, the film stiffed commercially, and now its most prominent place in pop culture is it leading to the creation of the phrase “Manic Pixie Dream Girl”, by one Nathaniel Rabin (not to mention it marking the inspiration and start of his beloved “My Year/World of Flops” series). So, is it a fiasco, a failure, or a secret success?

Can I be frank for a second? *hums a few bars of “Fly Me to the Moon”* Okay, thanks. Anyway, if I can be frank for a second, any movie that opens with an old-timey version of the logo of its studio is automatically on my good graces. Well, this opens with the old VistaVision Paramount logo, high grain level and all. Already, I’m wondering why this movie wasn’t deemed a masterpiece on the spot. I want to live in a world where a film is not judged by the quality of its contents, but by the quality of its studio logos. Any film produced by New Regency would automatically get an F in this world.

As the film opens, a shoe has been recalled in astonishing quantities. We soon meet the creator of that shoe, Drew Baylor. Drew is played by Orlando Bloom, who may be able (not very convincingly) swallow back his English accent but who can’t hide the fact that he is simply not a very good actor and a rather bad pick to play a central Cameron Crowe dreamer. Obviously, Tom Cruise and Matt Damon have the charisma to pull off that character (I may kind of hate Zoo, but Damon is very likable in it), I think Patrick Fugit is a good choice for the portrait of a Crowe character as an awkward young man, and even Bradley Cooper on autopilot has enough baseline charm to get through the door right before it smacks him straight in the face. But Bloom, when he wants to sound effortlessly charismatic, just sounds smug, and otherwise is just a placeholder in a shirt. This is a problem, as Drew is, you know, our main character, and he has to deliver a whole bunch of Crowe dialogue, which has sounded flowery and fake. You’ll wish Crowe had made the shoe the protagonist.

This shoe, covered in a “this is everything we didn’t cut from this storyline” montage (which would reappear at the beginning of Aloha), ends up costing it and Drew’s company $971 million (helpfully, Drew’s boss Phil, played by Alec Baldwin, tells Drew that this can be rounded up to $1 billion). This, understandably, sends Drew into a stupor, despite him greeting everyone at the company with “I’m fine”. When he gets back to his apartment, he immediately puts all his possessions at the curb and constructs a suicide machine (with a knife and exercise bike) that’s so whimsical it might as well come from a YouTube video called “What If Wes Anderson Directed The Fire Within“. But thanks to the most inconsistent ringtone imaginable, he’s lulled out of killing himself right then and there by his phone. His sister (Judy Greer) has called, and it’s because their father has died. Since the father died while visiting family in Elizabethtown, Kentucky, Drew has to go to Kentucky to retrieve the body and outfit it with the dad’s favored blue suit. On his plane ride there, he spends a lot of time with flighty flight attendant Claire (Kirsten Dunst), who’s essentially the same character Emma Stone was playing in Aloha, except she’s obsessed with names rather than Hawaiian folklore and is never revealed as anything besides lily-white. She’s bubbly verging on psychotic, and of course she will teach Drew to love life and to get on exit 60-B. Once he takes the exit to Elizabethtown, he finds himself driving through a town where everyone there points him where he needs to go and waves at him (I’ll admit, this got me just a bit). There, he meets with the rest of the family, which includes Paul Schneider (who gets the immortal line “This loss will be met with a hurricane of love”), Loudon Wainwright III, and Paula Deen (yes, that Paula Deen), all of whom are folksy, lovable people who may just bring Drew back to life when they’re not screaming at the top of their lungs. They also have very different ideas about burying the dad than Drew or his immediate family do. And then there’s the matter of Drew’s mother (Susan Sarandon), who becomes a bag of quirks with red hair in the wake of her husband’s death. And the marathon phone conversation Drew and Claire have while Drew is the only one in his hotel not there for a wedding (specifically, the wedding of Chuck and Cindy). It’s almost as if Drew won’t kill himself when he gets back home.

Know how I started this piece by saying that I sort of find Aloha endearing? Well, after seeing Elizabethtown, I honestly may find it a little less endearing, because Elizabethtown is the movie Aloha was trying and failing to be, a look at a man building himself back up after failure with the help of a spunky young woman. This is not to say that Elizabethtown is the great movie Aloha could’ve been. Like Aloha, the first part of this movie is pretty bad, with dialogue that suggests that it was written by a man very close to overdosing on cough syrup. But while Aloha merely settles into a bizarre, bad rut, this actually improves a lot. The dialogue is still insanely overwritten, but it begins to become less of a distraction and more of a part of a beautiful, unwieldy, sometimes utterly inexplicable tapestry. Not to say that the movie becomes utterly irresistible at a certain point; the grating comedy of Sarandon trying to do everything after becoming a widow (not to mention her goddamn memorial speech, which runs for roughly the length of the Nuremberg trials and distinctly resembles Sweet Dee’s awful, bodily function-obsessed stand-up on It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia) should’ve been the first thing Crowe cut after Toronto and Bloom is just a drip. But not even Bloom being a nonentity really matters when he’s opposite Kirsten Dunst. Yes, Dunst is the manicest pixie dream girl you could imagine, but she’s giving 294% to this type and is utterly winning in her near-insanity as a result. You can see Emma Stone playing the exact same beats in Aloha, and while she was the best part of that movie, there she’s hitting doubles with her role, while Dunst is hitting home run after home run with it. And then there’s the music. This is the last movie Crowe made with his then-wife Nancy Wilson as a music curator and this is a pretty wonderful swan song for her, fitting in many great songs (mostly just in the last 15-minute sequence where Drew embarks on a meticulous Claire-curated road trip home) and score pieces that almost entirely fit the moment and make the film much better than it would have been (just look at We Bought a Zoo to see how post-Wilson Crowe fucked up the music, making the score much too sugary and screwning up some seemingly un-screw-uppable needledrops, and made that movie worse). It all adds up to making something really enjoyable (and, honest-to-god, borderline transcendent at the end) despite its myriad flaws. I’m calling this one a secret success, guys.

Screw That, Let’s Talk Pretty Pictures: From literally the first shot, of a blown-out, barely blue sky overlooking a truck delivery, Toll delivers the magic in this film’s look. Given the film being a story of a city boy finding himself in a small town, you’d expect Toll and Crowe to want to make the city scenes look as distant and cold as possible compared to the Elizabethtown scenes. Thankfully, they follow Drew’s course and go off the beaten path a bit, staying with a consistently strong look for both locations. Compared to the consistent sunshine of Toll’s work on Almost Famous (or the photography of Aloha and We Bought a Zoo), the lighting here is often a bit more muted, favoring softer, less overbearing whites and some pronounced blacks, befitting the film being a bit of a sadder story than some of Crowe’s other work. It’s only when Drew hits the road that Toll allows the sun to really make its entrance into the film, flooding his car with beautiful light and really reminding him of why life is worth living.

Favorite Shot: It’s one in Phil’s office, he and Drew dwarfed by the production design and by the giant window overlooking them, with some beautiful clear light coming through the window.

Is It Worth Watching: Absolutely.

Stray Observations:

- You may not be able to discern the reedit scars as clearly as you could with Aloha, but they’re definitely there, especially in regards to one character in Elizabethtown who conned the father out of money. This is mentioned once and the extent of the pay-off to that is maybe five seconds of him apologizing for that and getting cut-off mid-apology. Also, Jessica Biel gets pretty high-billing for someone with as little screentime and important as she ultimately has.

- At one point, Claire tells Drew that she’s going to Hawaii (she isn’t), and says “aloha” to him twice. The Crowe Cinematic Universe is up and running baby!!!!!!one!!!!!!!!!!!!!

- During one part of the ending, Drew visits the location of Martin Luther King’s assassination and what plays on the soundtrack but “Pride (In the Name of Love)”. Yes, this is horribly obvious and probably more than a little offensive, but I can believe that it would be something Claire (she of little filter) would set up. Also, “Pride” is a kickass song and any chance to play it is a good one.

- Hold up… is this an episode of The Narrator Talks U2 to You? I believe it is. Anyway, since the last episode I went out and I bought myself the Innocence + Experience: Live in Paris concert film on Blu-Ray. I haven’t watched it yet, but I’m sure it’ll be killer, just like all of U2’s other performances. I have, however, watched Carl Franklin’s High Crimes, which is about U.S. crimes in late-80s El Salvador and features none other than the first half of Adam Scott Aukerman. And yet, despite all that, “Bullet the Blue Sky” is not used once as a music cue. Maybe Nancy Wilson should’ve married Carl Franklin after she divorced Crowe. And I guess that’s it for this episode.

- Great ep.

- I want everyone to check out the great podcast Blank Check with Griffin and David, where #thetwofriends Griffin Newman and David Sims discuss the work of filmmakers who were given blank checks after initial successes. They’ve already covered M. Night Shyamalan and the Wachowskis, and are now on, you guessed it,

Frank StalloneCameron Crowe. It will only be *checks watch* a little under four weeks from when this is posted for them to get to Elizabethtown! Maybe more! - Paul Schneider is also in Woody Allen’s Cafe Society, which is beyond the can’t-miss hit of the summer that was Irrational Man and into becoming the can’t-miss hit of a generation. Which generation, I’ll figure out later.

Up Next: The heart wants what it wants, and it wants to cover Francis Ford Coppola boondoggles.