Who Shot It: Giuseppe Rotunno. Rotunno began his film career when director Luchino Visconti needed someone to replace fellow all-time-great DoP Robert Krasker on Visconti’s Senso and decided on Rotunno (the film’s camera operator), who shot the film’s final scenes. Visconti and Rotunno would work together on four more films, a collaboration that’s truly the definition of quality-over-quantity; in the space of those four films, they created Rocco and His Brothers, Le Notti Bianche, The Stranger, and, best of all, The Leopard. If Rotunno disappeared after that, his legacy would be secure, but he kept on trucking and churning out some beautiful-looking films for other directors. His other major collaboration was with Federico Fellini, the two starting off together (they were going to work together on 8 1/2 before Rotunno couldn’t make it work with another, later-delayed, project) with the omnibus film segment “Toby Dammit” before working on Satyricon, Amarcord, Roma, I Clowns, Casanova, and And the Ship Sails On. He began working in America in 1960, shooting Stanley Kramer’s On the Beach. Later, he would shoot John Huston’s The Bible, Arthur Hiller’s Man of La Mancha, and Mike Nichols’ Carnal Knowledge, as well as staying in Italy to work with Vittorio De Sica on Sunflower and Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. He would be nominated for an Oscar for his brilliant work on Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz, and later for Terry Gilliam’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. Other than Munchausen, Ship, and Robert Altman’s Popeye, he didn’t have a particularly inspiring 80s (although he did shoot the first film to be shot on HD video, Julia and Julia). His 90s wasn’t a whole lot better either (he retired from filmmaking before the decade was up), seeing him work with a past-his-prime Dario Argento on The Stendhal Syndrome, Sydney Pollack on his remake of Sabrina, and, once again, with Mike Nichols on Wolf and today’s entry, Regarding Henry.

What Do You Mean, Story?: I’m not stupid. I know that Star Wars: The Force Awakens is going to make all the money this weekend and every weekend to follow. I know that getting those Star Wars clicks is essential to staying alive this week. So, I hope you’re happy, I’m meeting you halfway, you stupid hippies nerds. This week, I’ll be covering the first collaboration between writer Jeffrey “J.J.” Abrams and actor Harrison Ford. That’s right, in preparation for Star Wars, I will be covering a movie about how the mentally handicapped are the purest ones of all.

In his time as a director, Mike Nichols had a rather remarkably consistent career quality-wise. Sure, he dropped the occasional dud in there (the big ones being What Planet Are You From? and Day of the Dolphin), but they were spread out over four decades, never accumulating enough to create a bad streak. And he managed to not only survive the 80s, but maybe even thrive in the 80s and beyond, which killed or nearly killed many of his fellow great 60s/70s directors. But, of course, I won’t be talking about one of those great films he made in the 80s and 90s. No, I’ll be talking about one of his recognized missteps, the misguided 1991 drama Regarding Henry. But is it all that bad? The answer may surprise you, or it may not.

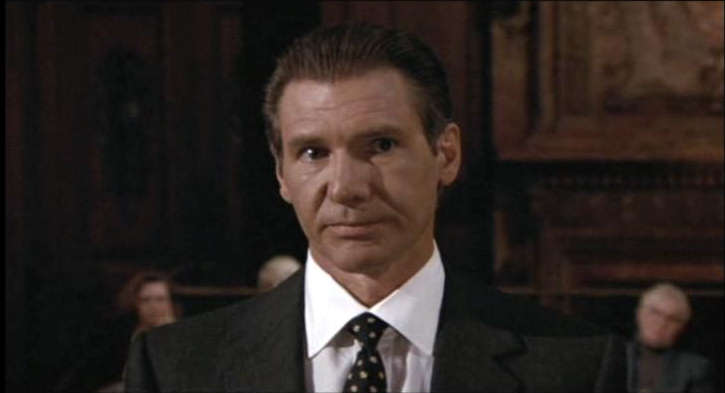

Henry Turner (Ford) is an asshole. How much of an asshole? He’s a lawyer, the kind of lawyer who argues that the court should not compensate a sweet old man in a wheelchair for some kind of in-hospital injury because he didn’t say that he was diabetic. He goes Carol White on a designer whose table for his apartment isn’t to his satisfaction. He goes off on his daughter for spilling grape juice on his piano, is coerced by his wife (Annette Bening) into apologizing for it, and then gives the most half-assed non-apology possible. His hair is slicked so far back it makes one wonder if slicking it back further would remove it from his scalp. He smokes and talks on the phone at the same time. One night, he goes out for cigarettes, refuses to give a mugger (John Leguizamo) his wallet, and is shot repeatedly for his troubles. He falls into a coma, and as a doctor played by James Rebhorn explains to his wife, his motor skills and memories are severely impaired when he wakes up. He doesn’t remember his wife or daughter, nor the fact that he looked like Patrick Bateman’s older brother, the one who kept giving him noogies. Faster than you can say that it’s hip to be square, Henry is out of the hospital and into a rehabilitation center, where he’s assisted in his recovery by a feisty physical therapist played by Bill Nunn. Nunn is so much fun in the part (you believe it when Henry doesn’t want to leave him) and Ford is so not-embarrassing as someone quietly putting the pieces back together that their scenes threaten to make the movie good. The honeymoon is over for both Henry and the viewer when he returns home, and it’s pretty much all downhill from Ford asking the maid what he did when he was alone in the house, with the maid replying that he works literally all the time. By the time Henry is exploring New York, including seeing a dirty movie, with childlike wonder, the only response is that of a full-body sigh. It doesn’t help that Ford has devolved into something close to “full-retard” mannerisms at this point (three-quarters-retard, maybe?), and for the rest of the movie, where he becomes more emotionally involved with his child by being sad when she has to go away to a private school, loves his wife more than he did, and questions why he hid evidence in that hospital case. For you see, he’s wiser than us, and he feels the world the way it really is and (We apologize for this unfinished sentence, he didn’t finish it due to a sudden projectile vomiting spell. -Editor)

This is an exceedingly well-made movie. Mike Nichols’ direction is excellent, knowing when and how much to move the camera (there are no “look-at-me” show-offy camera movements). He also doesn’t lean too heavily on Hans Zimmer’s (pretty dated, chintzy) score, which would be a big crutch for other directors making the same movie. The film was edited by Nichols’ regular editor and fellow 70s cinema legend Sam O’Steen, and, befitting a film cut by the editor of Chinatown, the editing here is top-notch, cutting when there needs to be a cut (like from Henry’s wife learning that he doesn’t remember her to her silently moping on the bed) and letting scenes play out patiently, without unnecessary coverage. So many movies I watch for this series are utterly punishing due to their slack pacing, but the pacing here is good too, never letting things get boring. Other than Ford, the acting is great, especially from Annette Bening and Nunn, and even from the kid actor playing Henry’s daughter (I love how, in one scene, Henry is flicking paper balls at her, and she only slightly suppresses a grin before telling him to stop). This film seems to have been created on a dare about how far great filmmaking can take a not-very-good script. The answer is pretty far, but still not far enough.

Yes, J.J. Abrams’ script is based around the notion that the mentally-challenged see things so much clearer than everyone else (after all, this movie ends happily when Henry still has the mental capacity of an adolescent, at very most). But there’s a good movie to be made about any subject, dare I say it. This is not that movie. Abrams’ script is simplistic and cloying, throwing in far too many easy moments for the audience to boo (like when some of Henry’s “friends” remark how he went from “a lawyer to an imbecile”) or cheer (at the very end, when Henry rescues his daughter from her private school). And then there’s the cheap, much-ballyhooed device of having Henry obsess over Ritz crackers early in his recovery solely to use it as a way of getting it across to him that he had an affair at the Ritz-Carlton. No matter what one thinks about Abrams, one can’t deny that he went uphill from here, because at least when his movies are stupid now, their stupidity is wrapped in such pretty paper that it takes awhile to realize it. Maybe that’ll even be what happens when Star Wars comes out and (We apologize once again for this unfinished sentence. Tragically, as he typed this, The Narrator was taken from his home to an unknown location by a band of Star Wars fans. We have completed the rest of this entry from his notes on the film. -Editor)

Screw That, Let’s Talk Pretty Pictures: With so many movies where a mean, yuppie character is redeemed, their initial life is told visually with lots of cold, dim colors. But what Rotunno does here with the colors is much more inspired than that; those early scenes are significantly richer in contrast and color than the later scenes. Henry’s first scene on-screen is in the courtroom, with its umber walls and hard lighting (Rotunno used hard and soft lighting before to differentiate between the real-life and “dream” sequences in All That Jazz). When he goes home, his apartment is similarly contrasty, not nearly as inhospitable, but still ever-so-slightly ominous. Generally, these redemption movies start with their characters in Purgatory. Here, Rotunno and Nichols want you to know that Henry is in Hell. After Henry is shot and comes to, the palette becomes much more neutral, Henry switching from pitch-black suits to light-blue shirts, and light enters Henry’s world like it hadn’t before. But my favorite thing about Rotunno’s work here is the study in opposites of the first and closing shots. In the first shot, the camera pushes onto the door of a courthouse while it snows. In the final shot, the camera pulls out onto a pristine landscape as Henry, his wife, and his daughter leave the school

Favorite Shot: A perfectly-centered shot of Henry returning home, observing the table he doesn’t like and chairs covered in plastic, perfectly encapsulates the emptiness of Henry’s initial existence better than any bits of dialogue could.

Is It Worth Watching: I mean, this is a turd that’s been polished to a shine. But, it’s still, you know…

Stray Observations:

- Lookee at that screenshot above. That’s none other than nerds’ lord and savior J.J. Abrams making his scintillating screen debut as “Delivery Boy”. He doesn’t have any lines, but he makes the role his own.

- This following comment is directed towards those who clicked on this solely for the Star Wars angle; you’ve made it this far into an article about the aesthetic analysis of a forgettable, banal feel-good movie that really has nothing in common with that movie you’re going to love besides the obvious. For your troubles, I gift you this; a photo of Oscar Isaac and Adam Driver at the Star Wars premiere.

Up Next: I dunno. Here’s that image again.