…how can I place his order, his disintegration?

Let’s tell a story: You’re a struggling young reporter sent to cover a soccer match in a town you think you’ve never visited. You arrive a few hours early and decide to grab a bite to eat, maybe soak up some of the local color, before the match begins. Only… hold on a moment, you have visited this town, and the memories start rushing back: you’d forgotten — you must have willed yourself to forget — because the friend you knew here, a close friend with whom you had a sometimes contentious relationship, had died so young and so unexpectedly from an aggressive cancer, and you just… pushed it all away. You’ll still eat your lunch, you’ll still cover the match, but over these next few hours, your mind will be a swirl of half-recalled memories, snatches of moments, some funny, some melancholy, and in no particular order.

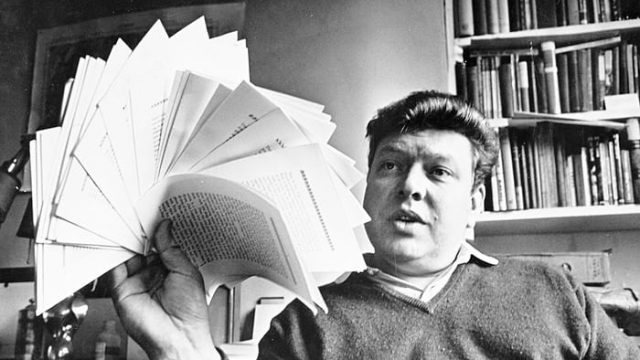

That “no particular order” was a major sticking point for B.S. Johnson, the author of this quasi-memoir, and one of the boldest, funniest, and most melancholy authors I know. He could have used the most obvious, ready-made form for this challenge — even high school students know what “stream of consciousness” means — but, in addition to feeling stale by 1969, it also felt wrong. That paradox of stream-of-consciousness literature is that it lends concrete and chronological shape to an experience that is neither; it gestures to experience by rearranging material in the sujet to give the reader a “sense” of that mental jumble, but the work itself is presented to the reader as a complete, chronological portrait of that process. But what if we took the “no particular order” of memory and made it the literal form of the work?

B.S. Johnson’s The Unfortunates is an attempt at that book: it consists of 27 separately bound chapters with only the first and last chapters in a “required” order: the reader is invited to shuffle the middle 25 chapters and read them in any order at all. The effect would still capture that stream-of-consciousness jumble, but in a more erratic, more unpredictable, and more personalized way. Johnson felt that he hadn’t quite cracked the code here (after all, the fabula, the events, are still in a defined order: Tony was alive, then Tony was not), but there’s no doubt that reading this book, the tactile nature of the experience, the emotional randomness that results from the shuffling, is a rare experience in literature. Let’s see how this works.

The Unfortunates begins with a short first chapter to guide the reader into the material: Johnson has stepped off the train in shock (“But I know this city!”) and immediately the hazy images to start to coalesce around a name: Tony. Tony is dead and Johnson will use this book as a chance to revive him, so to speak.

After that opening chapter, every reading is a new experience. My chapter two begins,

Again the house at the end of a bus-route, again the fish and chip shop lunches, working together in that front room, Tony saying I could gather a whole range of material if I just listened to the gossips who stood, sometimes for an hour or more, outside the front window and could be heard perfectly clearly.

What an auspicious pick! Here at the beginning of the book, this has an almost clarion-like effect (e.g. “Once more unto the breach”): a ringing poetic welcome back to this world. Those first two phrases just beg to be read out loud. (“Again” is a great word for an opening. Du Maurier used it to awesome effect in Rebecca.) Johnson even preps us somewhat for the nature of his material, being invited to gather the stuff of everyday life from the speakers outside. The effect would be different if we read this at the end, once we’ve already been introduced to the bus routes and fish-and-chips, trading the high poetry of an opening for the melancholy nostalgia of a closing. Both effects are great, different as they are, and both are by chance.

But look, my chapter three is less concrete… Now Johnson is struggling to place a memory:

His dog, or his parents’ dog, in the outback of Ewell. The long streets, the useless grass verge in front, the path, the concrete thirties road with the frayed rubber expansion joints between sections. It must have been summer, yes. Why else would we have been there? Did we go together?

This is the basic rhythm of The Unfortunates, a Hopscotch-like journey through Johnson’s recollections and emotional moods. The story never changes, but the effect does. In your reading, the melancholy chapters might all come first, followed by the funnier and more optimistic ones; the book may thus feel more warmly human. Or the reverse: the warmer chapters may give way to Johnson’s sour, occasionally misogynistic cynicism. The act of reconstruction doesn’t discriminate between his moods. Your opinion of Johnson, your opinion of how Johnson processes Tony’s death, may depend on the fragile luck of a good shuffle, but part of Johnson’s brilliance here is allowing us the freedom to have a bad shuffle, to find the worst possible version of himself in the material.

The longest chapters are 12 pages; one deals at length with Johnson’s own emotional and sexual immaturity. One of the running themes of The Unfortunates, and maybe its least well-aged, is the author’s own narcissism, his inability to let go of his ex-girlfriend Wendy despite the ostensible focus of the novel being the death of a friend. It’s true to life (Johnson was obsessed, and troubled: he committed suicide at the age of 40) and plenty raw in its emotions, but the passing of the Age of Great Male Narcissists hasn’t done that aspect of the novel many favors. Meanwhile, the shortest and most brutal chapter is Tony’s death, a single paragraph describing a phone call that delivers the news, a shock after what they thought was a recovery. My shuffle places it around chapter 22, after I’ve come to know Tony pretty well. Here, the moment cuts deeply, even though I knew it was coming. What if it had come in the opening chapters? How would I feel about the false recovery, the sudden death, with almost no context yet given?

For all the heaviness of these memories, Johnson can also be a mischievous writer, and one of the funniest I know. In one section (which I get near the end on this shuffle), he finally attends and reports on the soccer game, which he has to deliver to the paper via an outdoor public telephone, grammar and all. (In the excerpt below, the larger spaces are Johnson waiting while the other end of the line types out his report.) Just read this beauty out loud:

But apart from these two chances comma the waves of Citys apostrophe s attacks broke on Mull comma Uniteds apostrophe s sweeper comma the relentless destructiveness of whose tackling claimed a casualty just before halftime when Wisdom went off with a suspected broken bone in his foot to give Beresford comma the substitute comma yes Beresford with one r and two ees Beresford comma the substitute comma his first game for City full point new par

Funny enough, you might come across this passage before the one where he actually shows up to the game: not all the chapters are memories, strictly speaking, and some of them do have a logical order. You might find him eating lunch in the middle of a set of chapters where he’s already left for the match to “get on with the bloody job.” The shuffle might give you a thoroughly realistic account of this day in the Midlands, or a surreal timescape where cause and effect seem unrelated. Whether that’s a concession to the limitations of the form or just another of the book’s audacities (a set of unordered memories about a set of unordered memories), it doesn’t matter much. The chapter order doesn’t affect anything as far the overall stuff of narrative, or rather: it’s all affect. Real choice in literature is an illusion, as Raymond Queneau tried to demonstrate half a century ago.

By way of conclusion, we should note that The Unfortunates is far from the only book-in-a-box; heck, it wasn’t even the first. That designation likely goes to Marc Saporta’s 1962 work Composition no. 1, which was translated a few years ago by Richard Howard and published in a very cool-looking set by Visual Editions (they even include a randomizer for e-readers!) Saporta’s is a much more radical (though ultimately less satisfying) experiment in which every single page is separate. Bits of plot and character spring up across the collection’s 150 pages—the German occupation of Paris, a robbery, a car crash—around a handful of recurring characters. Some nice turns of phrase and occasionally sharp observation, and though it unfortunately lacks the wit and specificity of Johnson’s work, it’s a fun and quick read.

Much more in line with Johnson’s pathos is Chris Ware’s critical darling Building Stories, a book-in-a-box that illustrates the life of Ware’s unnamed protagonist as she grows up, matures, and becomes a mother herself. It is, like so much of Ware’s work, melancholy to the point of grim (this is not a complaint), but livened by flashes of wit and warm humanity. In some ways Ware’s box is more radical than Johnson’s: Ware plays with the medium itself, giving us broadsheets, flipbooks, children’s storybooks, and newspapers to emphasize the physicality of this process of recording a life (a recurring theme of the book is transience, so the physicality — the evidence of a life lived and recorded — does matter.) On the other hand, there is a chronological order that can be recreated, since the protagonist’s life stages are more or less clearly defined. How you choose to approach that, though, is up to you.

Also focusing on physicality as such is the book-in-a-box S. by Doug Dorst, based on an idea by J.J. Abrams (really). This box contains only one book, The Ship of Theseus, but that book is stuffed with letters, maps, postcards and other paraphernalia. There are two narratives here: the one contained in Ship of Theseus by the fictional author V.M. Straka, and the running commentary by two university students, who leave inked notes in the margins about their own attempts to unlock the book’s mysteries. Meanwhile, the physical objects they have slipped between the pages serve as an extra level of “evidentiary” material. I wish the result were anywhere near as compelling as that summary, but I have nothing positive to say about the book other than that the production values are top-notch and I’m always happy to see artists trying new things.

As for B.S. Johnson himself, the “one-man literary avant-garde,” The Unfortunates was not his only attempt to shake up the moribund form of “the book.” For example, his second novel, Albert Angelo, borrows Ulysses‘ approach to changing style in each chapter, but undertakes more radical revisions than Joyce could have imagined: in its most famous chapter, a literal hole cut through the pages lets us know exactly what the protagonist will face down the road. Albert himself, a recent graduate suffering the indignities of teaching high school while dreaming of fame as an architect, is a bit too bitter a protagonist (not unlike the Johnson of The Unfortunates), but once again, Johnson’s own puckish sensibilities make for an enjoyable ride.

My favorite work of his, House Mother Normal, is conventional enough as a “bound book” with no pages distressed, but its formal conceit, I leave for readers to discover. The book provides a day-in-the-life of a somewhat grubby nursing home, each chapter the internal monologue of one of its residents. Like The Unfortunates, it manages to mix the devastating and hilarious in some unsettling but memorable ways. Its last page slapped me in the face like nothing else, and if you’ve never had that experience before: friends, find you a book that slaps you in the face.