On this day in 1558, Elizabeth I became Queen of England, ushering in an era that could only have been called Elizabethan. As it happens, it’s the wrong week to pay tribute to her, because (in case you hadn’t noticed), I alternate weeks. Therefore, I will take this opportunity to talk about someone whose career almost certainly would not have existed without her support and love of theatre, someone whose influence on movies goes beyond the 450 movies, 599 TV shows, 265 shorts, 62 videos, 11 documentaries, and three video games on which IMDb credits him as author.

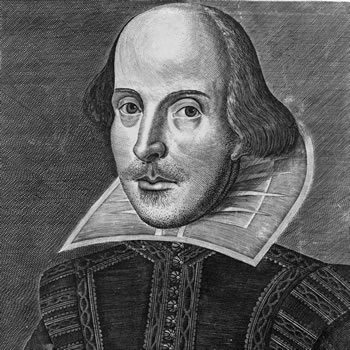

We don’t know how to spell his name. We don’t know for sure what he looked like—the most famous portrait of him wasn’t done in life; the portrait done in life cannot be proven to be him. We don’t know what he, personally, believed about much of anything. We know exceedingly little about him compared to what we expect we should, though it does not of course take much research to know how much more we know about him than we do about any number of the famous people of his era. (We know more about Elizabeth, but of course we do; we always know more about queens than commoners.) Documentation was just beginning to be considered important in that century; ask anyone tracing their family tree how hard it can be go past a certain point unless they luck into a prominent line.

It is true both that Shakespeare shamelessly borrowed plots, characters, and even actual dialogue from other writers and that there is no reason to believe that he didn’t write that which he didn’t borrow. The former was honestly not uncommon in his age; Bill Bryson’s excellent book about the author gives examples from Spencer and Marlowe. But there has never been a believable candidate for the latter, even if there were a good reason to believe that the man himself didn’t write them. Certainly it never ceases to amaze me how many of the candidates (including Elizabeth I, come to that) were dead before Shakespeare stopped producing plays.

Not all the plays are good. I who love Shakespeare am assuring you of this. Some, I wonder if they’d be funnier if you were actually living in his era; some of the jokes don’t translate very well. In point of fact, my freshman English teacher took a class period to explain the dirty jokes at the beginning of Romeo and Juliet, recognizing as the man himself did that the way to suck people into your story is with a little funny filth. But even the bad ones are enough to justify what Pamela Dean said of Troilus and Cressida in her novel Tam Lin—”I always forget what gems are buried in that dung-heap.” Honestly, some of the writing isn’t outstanding, but when it is, there’s none better.

And let’s be real—for four hundred years, people have been borrowing plots, characters, and even actual dialogue from him, credited and uncredited. Kenneth Branagh got a Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar nomination for his unabridged film of Hamlet. Stephen Sondheim’s most successful work is the lyrics for West Side Story. And, of course, there’s Kurosawa and Ran and Throne of Blood. The acknowledged adaptations can go on for days, obviously; I wonder and do not care to sit and calculate exactly how many hours of adaptation all that stuff at the top works out to.

But not all borrowings are credited, either. This isn’t just that he isn’t listed as a writer on Slings and Arrows despite the show’s being set actually at a Shakespeare festival. (Not even a thanks; I’m honestly a little sad to discover this.) This is how often you see the stories play out; I maintain, for example, that if The Lion King rips off Kimba the White Lion, Kimba the White Lion is ripping off Hamlet. This is how often lines are borrowed. Character names—the first use of the current spelling of “Jessica” is in The Merchant of Venice. And I would be interested to see if it’s possible to write much of anything without using a word first documented in the plays of Shakespeare.

Help me afford a good annotated Complete Works; consider supporting my Patreon!