There is a progression of beginning piano. Everyone starts with “Chopsticks,” of course. Usually followed by “Heart and Soul.” Then you go for things like “Fur Elise.” Eventually, everyone learns “Linus and Lucy.” As a former orchestra kid, I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard it played on pianos in practice spaces. I can’t play it myself, but then I don’t play piano even at the “Chopsticks” level. However, I can probably list about fifteen or twenty people I knew in those days who played it, and I don’t know how many of them could name Vince Guaraldi on a dare.

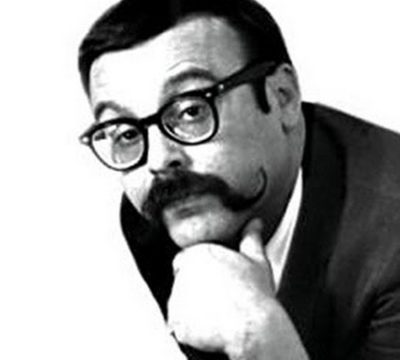

Actually, Guaraldi’s first album included “Chopsticks Mambo,” so there’s that. Two of his maternal uncles were jazz musicians, one of whom has his own Wikipedia page. He spent the ‘50s and ‘60s bouncing around varying music groups and labels; his children have at some point sued his former label Fantasy Records, who were keeping 95% of his royalties and owe the estate literally millions by their estimation. He even composed a jazz mass for San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral, which is probably a lot more difficult to play on solo piano.

Lee Mendelson initially heard Guaraldi’s “Cast Your Fate to the Wind” while driving across the Golden Gate Bridge. Peanuts is such a Bay Area phenomenon, regardless of what people know about it and where Charles Schulz was actually from. Mendelson hired Guaraldi to score his upcoming documentary A Boy Named Charlie Brown. Guaraldi called Mendelson at one point to play some of the music; Mendelson didn’t want to first hear it over the phone, but Guaraldi said he had to play it for someone or he’d explode.

From then on, his career was basically Peanuts. He released a few other albums that weren’t terribly well-received, but he was basically the Peanuts guy—and he loved it. His style evolved; he embraced more rock, for example. But he was happy with what he was doing. Had he lived a little longer, he was to have gone on a cruise where he would have played Peanuts music, and he was really happy about it. He was still performing live, mostly in Northern California, in addition to the composing he was doing for Mendelson and Schulz.

He died of medical malpractice. He went to a doctor, and he was diagnosed with “probably ulcers.” Just days later—exactly ten months before I was born—he collapsed at a jazz club in Menlo Park, California. He’d gotten up from where he was playing. His last song was his interpretation of “Eleanor Rigby.” He collapsed on his way to the bathroom. Had a doctor taken his symptoms seriously, he might well have had decades more of productive work. It’s unlike he’d be alive today, given he’d be closing in on a century, but he deserved to live past 47. Which is my age. We could have had so much more.

Help me pay for the plumber who’s coming to our house today by contributing to my Patreon or Ko-fi!