“Remember, God didn’t say ‘I’m gonna make light now,’ He said ‘Let there be light.’ His first act was to allow light into what had been Nothing.” (Thomas Pynchon, Against the Day)

Stan Brakhage’s The Wold-Shadow (1972) begins with a straight-on shot of a forest, darker than you’d expect, with only the slightest ripple of branches and leaves to show that it’s not a photograph. Then it begins to change. The camera, and therefore our gaze, never leaves its fixed position, but the image brightens and darkens like a pulse, the light going down until nothing appears but the bare verticals of trees. Then the image turns to liquid (Brakhage painted on the camera lens directly), washing out to degrees of green and flowing but still retaining the elements of the original composition. At the end, Brakhage hard cuts to paintings in front of the camera rather than on it, abstracts of red and green and black where the paint still flows in the same tempo as the branches in the wind at the beginning, and then it’s done, what Brakhage called “a history of Western landscape painting from the Renaissance to Clyfford Still, if you consider Clyfford Still a landscape painter, and I do.” It is that history, and it’s a way of seeing photography, art, and cinema different from than anything I’d seen before, and it’s just over two minutes long.

In his career of over fifty years, Brakhage made hundreds of movies, some of them based on the classic methods of narrative and of cinema: events occurring in chronological order, filmed by a camera. He made many if not most of his movies, though, without filming anything at all: films made by painting directly on the film stock itself, films made with pre-existing footage, and films that used one or both of these elements along with filmed images. Some of those filmed images are legible, others were pushed into abstraction. All the films in this category dominated the latter half of his creative life, and all of them point to a definition of cinema that goes beyond classic into something fundamental. Perhaps the most fundamental definition of music is “sound transformed over time”; Brakhage, who described his films as “moving visual thinking,” created a cinema of image transformed over time. Narrative is a series of events, and gets its power from making us ask “what happens next?” and Brakhage just walks away from the middle word. You can try as much as you want to assign a narrative to The Dante Quartet, Persian Series, “. . .” (Reel Five), or any of his other abstract films: many have and Brakhage is sometimes one of them and you may even be right. Narrative, though, doesn’t explain their power.

The power of music and of Brakhage’s films goes far beyond narrative, even if the creator intended one. (“A creation that has value and meaning beyond its creator’s intent” is a pretty good definition of life.) “Our joyous response to music is a response not to meanings but to the making of meanings,” sez Simon Frith; you can hear that in the way twenty people can hear the same music and never agree on what it meant, never even expect to agree. Abstract painters understood that by moving away from recognizable images and definable interpretations, they expanded their universes; so did Brakhage. Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Philip Guston, and others broke with the practice of representation and moved towards taking over space; noise artists broke with music played over a background and moved towards taking over sound; and Brakhage moved out of narrative to so many other ways of taking over light and time. All of them created works so sensual and direct and with such power that asking the question “but what does it mean?” and expecting some kind of right answer feels like a category mistake, like waterboarding a sunset.

The absence of narrative and of meaning, by the way, makes me recommend a different strategy for watching Brakhage’s works. These are not films that should be approached in a Sam Adamsesque spirit of submission (pretty much what Fred Camper recommends in his essay for the first Criterion Collection anthology of Brakhage’s films), where you sit in a dark room and pay close attention until you figure out their secrets. Take advantage of home viewing and let them play on the biggest screen you have and live your life, maybe even make some tacos, while they do; in their releases, Criterion has organized the short films into programs of one hour or more that can be played all at once to make this easy. That most of the films are silent helps too, although I’d be careful when The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Eyes (1971) comes up. These are not works of expression, there is not something you’re Supposed to Get here, and there will be no quiz at the end. These are monuments, and you don’t have to submit to the Grand Canyon to know its beauty and existence. Soon enough your favorites will catch your eye and you’ll pause and jump back and watch them through. Like great noise, the best Brakhages won’t let you ignore them.

Walter Murch said that editing was what made movies different from all other art forms; nowhere else do we see everything change completely in an instant, and accept that as normal. Brakhage uses edits in so many ways: to connect, to contrast, occasionally to build a narrative, but he always uses edits as a fundamental element of rhythm. In his player-piano music, Conlon Nancarrow created passages of notes that were much faster than anyone could play, so fast that the passages don’t sound as discrete sequences of notes but as their own new musical thing. Brakhage’s edits, especially in his hand-painted films, are like this too, cutting down to the level of changing every frame, and building sequences of energies of color. Like abstract expressionism, these films can’t be understood in terms of objects, but rather in speed, intensity, and density.

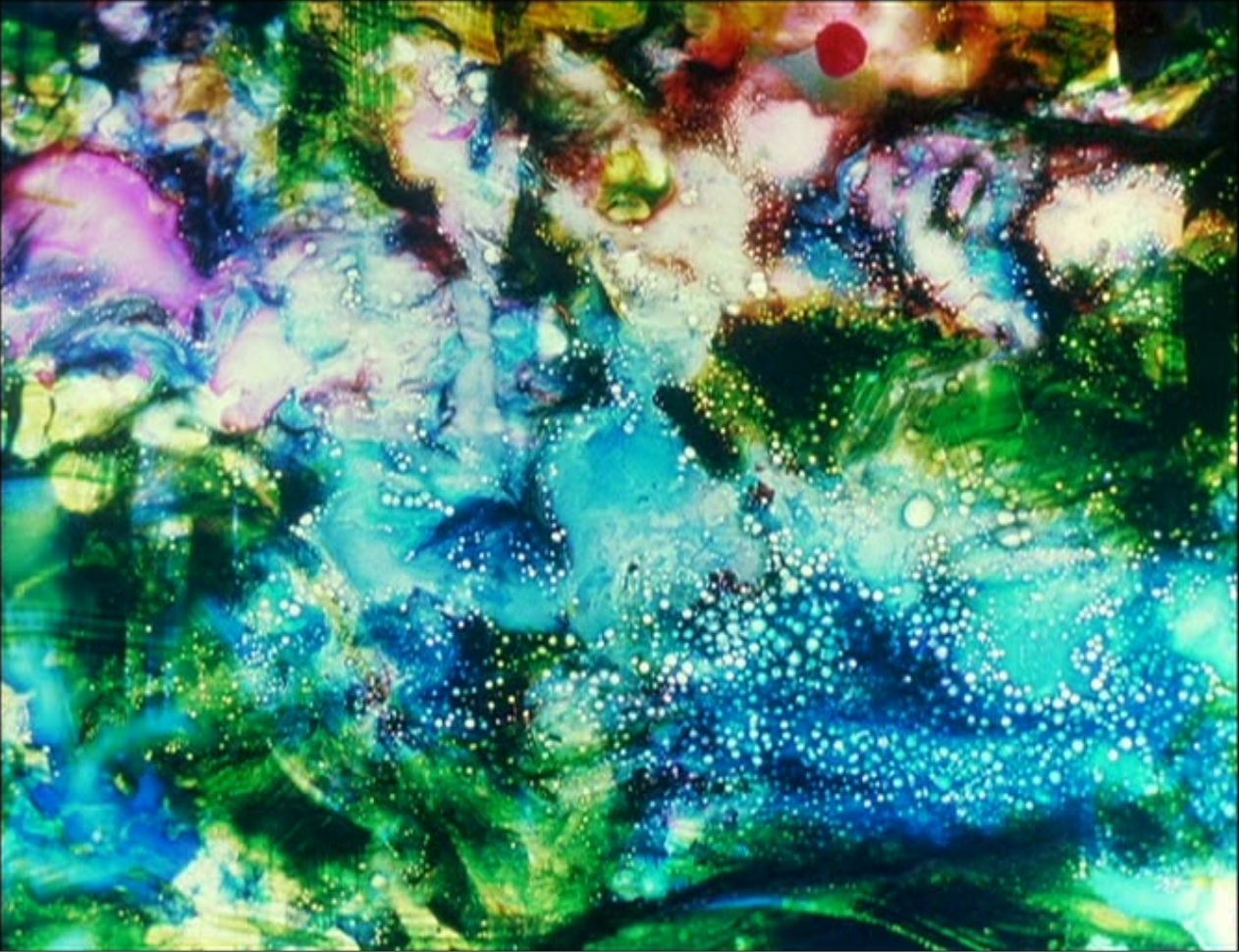

Maybe Brakhage’s The Dante Quartet (1987) has the clearest expression as music, and that’s why it’s among his best films. Just over six minutes and in four movements (“Hell Itself,” “Hell Spit Flexion,” “Purgation,” “existence is song”), it has the punchiness and overall structure of the Baroque, nothing drawn out, nothing lasting longer than necessary. “Hell Itself” plays hand-painted colors over a barely visible background, like a ground bass, and the cutting alternates between slower and faster patterns, both elements of the Baroque. “Hell Spit Flexion” lowers the density of the colors and cuts in filmed passages, but done with the camera moving so fast that it blurs into abstraction. Here, Brakhage maintains a fast tempo but not as fast as possible, and has moments where he stops and holds on a black frame. Also, he places everything within a smaller frame within the larger 4:3 frame, the visual equivalent of hearing a chamber ensemble play in the next room. “Purgation” happens in a widescreen frame inside the 4:3 frame, so the colors have come closer but haven’t fully reasserted the presence of “Hell Itself.” Brakhage accelerates the pace of the preceding movement, too, but drops the filmed material. Instead, he places the colors over different backgrounds–a room, a photograph–and slowly changes the colors to reveal them. If the backgrounds are basslines, Brakhage gives us moments when they’re all we see. The colors are less dense and more fragmented than in “Hell Itself,” shards rather than swirls. Another technique that’s new in this movement: he stops the fast sequence and lets the final image fade rather than cut to black. “existence is song” fully reasserts the frame, the colors, the fast and slow speeds, the use of imagery, and the fades to black in an exuberant finale of less than a minute. Here, the background images are cosmic–moon and sun and volcanoes–and often in motion, with the colors occasionally cut around them rather than overlaying. Although there’s a narrative progression of the background imagery (landscape, nature, domestic, cosmic), what makes it work is the overall structure here of three preludes and a fantasy, a demonstration of techniques and a grand summation of them.

Other Brakhage works take their structure and rhythm from symphonies rather than Baroque suites. Dog Star Man (1964) begins with a 25-minute Prelude, and the first minute of that is nothing but a pulsating, slightly shimmering deep red. It’s a Wagnerian beginning, calling up the opening chord of “Dawn” in Götterdammerung. Like Wagner, Brakhage doesn’t come off that red all at once, he only gradually cuts in other images that aren’t always recognizable as things: a street at night, his own face, flames, a moving landscape seen from a car or train. These cuts come faster than the colors, little instrumental riffs over the pedal point of red. Throughout the Prelude, Brakhage will cut between many kinds of images (many of which are of the moon or the sun or, with eclipses, both; the Solar Observatory in Boulder, Colorado gets a credit) but often too quickly or in too little focus to be perceived as images. Of his Sinfonia, Luciano Berio said “the experience of ‘not quite hearing’ is conceived as essential to this work,” and for the Prelude, not-quite-seeing is equally essential. What we perceive is the continual transition between images, or the overlay of them: the visual counterpoint. As the Prelude moves on, there’s a distinct key change as blue begins to predominate instead of red; there are also more recognizable images mixed in, held longer so we can see them: organs of the body, Brakhage’s wife Jane, Brakhage himself with a baby. The next part of Dog Star Man comes close to a narrative, and I’ve never found it as interesting; the Prelude makes the elements of a narrative emerge from a primordial musical flux of images. (Brakhage also edited a four-hour version of the one-hour Dog Star Man called The Art of Vision, where all the individual layers of the films are played in all possible superimpositions. That sounds like a fascinating exercise but not something worth watching, like making a piece of all possible combinations of the layers of a Bach fugue. It would be worth studying but what makes the layers work is hearing them all together.)

I’ve suggested before that what defines “symphonic” is the range of sounds and the length of time of their transformation, and the single movement of Dog Star Man’s Prelude is over four times as long as The Dante Quartet and over ten times as long as The Wold-Shadow, which is arguably based on a single image. Just as composers could incorporate more chords to create more transformations and longer works, Brakhage’s longer works require more images, and more ways of changing between them.

A digression: two of our excellent commenters, washington and Son of Griff, have pitched the idea that the later works of Tony Scott (Domino, Man on Fire) have a Brakhage-like approach to editing. Scott began his career as a painter, and does have some of the same techniques as Brakhage, such as putting words anywhere in the frame and not just in the usual bottom-center caption position. Scott never developed Brakhage’s level of sophistication in editing, never got to that supple, musical way of varying speeds and techniques. Scott’s one move was to speed up the editing until the continuity was lost; he wasn’t able to build different kinds of continuities out of that. Still, I don’t think he was doing it gratuitously. He was continuing down his mistaken path, with each film building on the techniques of the previous one, and he might well have made a Brakhagian narrative mainstream movie if he’d lived longer. It’s a sadness to all of us that he didn’t, but we’ll always have Enemy of the State and Beat the Devil.

One of his densest works in this respect is Yggdrasil: Whose Roots Are Stars in the Human Mind (1997), which Brakhage openly cites as a companion piece: “in [Dog Star Man], I had envisioned the World Tree as dead, fit only for firewood. . . .Now I am compelled to comprehend Yggdrasil as rooted in the complex electrical synapses of thought process.” Dog Star Man’s Prelude was a setup to a story, but Yggdrasil moves into thought. The earlier film had an overall medium tempo with lots of fast montages cut into it and this one moves at moderately fast speed for all of its 17 minutes. This is one of Brakhage’s most exuberant films, using all the techniques of Dog Star Man (traveling-through-landscape shots recur here) and so many of the ones he’d learned since then: filmed video, dissolves, optical printing to make images painted on the film zoom in or out or shift, objects collaged directly onto the filmstrip (done most famously in Mothlight). The Prelude had the grandeur of Wagner; Yggdrasil has the density and energy of Elliott Carter, something like A Symphony of Three Orchestras, the feeling of space getting lit up at every point. (A shot of fireworks going off feels like a moment of rest here.) Another close musical relative is Magnus Lindberg’s Action – Situation – Signification, where Lindberg alternated between chamber/percussion passages and recorded sounds of nature (Earth, Air, Fire, and Water). Where the Prelude was about the gradual emergence of objects, Yggdrasil shifts between object and image constantly. Objects don’t just emerge from the flux of color, light, and edge here, they also get absorbed into them and transformed into something else. It’s “moving visual thinking” at high speed, and I doubt it could go on much longer without exhaustion setting in.

Cat’s Cradle (1959) demonstrates the musical aspect of Brakhage’s works because it could have been done as narrative–”sexual witchcraft involving two couples and a ‘medium’ cat–but he chose instead to go for more associative, rhythmic, repetitive editing, one of the first works where he really did this. Brief images of the four people, a foot stepping on a pillow, wallpaper, frames of color, and the cat are all cut together at different speeds and combinations. With Window Water Baby Moving (also 1959) and The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Eyes, the speed of editing is slower. Two things result from this: it’s always clear what we’re seeing, so these films are about the things we see, not the film itself; and there’s a clear sequence of events. In Cat’s Cradle, the stream of images, accelerating or decelerating, flipping around a central vertical axis, holding on one image and then speeding into edits again, becomes a continuity without narrative. The images are not isolated pictures of things but part of an overall music; it’s like some of the early pieces for audiotape by composers like Edgard Varèse or Vladimir Ussachevsky, when the composer would pick several sounds and then build a collage out of repeating and altering them. The sounds or images don’t have to have any connection; Ussachevsky made his Piece for Tape Recorder out of “a gong, a piano, a single stroke on a cymbal, a single note on a kettledrum, the sound of a jet plane, a few chords on an organ” and made music by how he repeated them, how he moved the sounds in and out of attention, how he moved between them. The power of these works doesn’t come from the individual sounds or images, not what they mean on their own, but what the composer makes with them.

John Cage went the other way on this; he once said that in new music (his and others) there was a greater concern for “sound come into its own,” not bound to any kind of musical function: “a time that’s just time will let sounds just be sounds and if they are folk tunes, unresolved ninth chords, or knives and forks, just folk tunes, unresolved ninth chords, or knives and forks.” What Brakhage did was halfway like this: he shifted images away from things–from what they represented–by placing them in a musical continuity. Brakhage’s films are not image come into its own, but image come into music, closer to Dore Ashton’s remark that “modern music aspires to the condition of painting and modern painting aspires to the condition of music.” (Cage undermined musical continuity, and replaced it with nothing; Brakhage undermined narrative continuity and replaced it with music.) Brakhage’s works get really interesting, even disturbing, in the films when the music of images shifts back into representation; in Persian Series #3 (1999), there’s a moment when, amongst all the shifting colors (Brakhage zooms them in from the right side of the screen then zooms them out on the left), what look like a set of eyes appear. That comes back a few times and it’s one of Brakhage’s most unsettling moments, like the rules of the world got violated. It’s one thing to have Diego Velázquez put a mirror in Las Meninas so we see ourselves looking out at ourselves. It’s something entirely terrifyingly else to have a Jackson Pollock look back at you.

23rd Psalm Branch (1967), one of his better-known works, plays in the space between music and narrative. The first half-hour consists mostly of newsreel footage of war: bombings, dead bodies, bodies in a concentration camp, Hitler, Mussolini, marches, the cultural waste that wars always produce; if you need to explain the title, call it the branch of the river that travels along the valley of the shadow of death. Brakhage continually cuts frames of black into the footage, so we never see more than a second or two before the black frame appears. (He also cuts in frames of other colors, and later overlays the images with holes.) He continually breaks the most fundamental aspect of film, where seeing 24 still images a second becomes smooth motion. There’s nothing abstract about these images, they’re all horrible (late in this part we see Brakhage’s hand writing “I can’t go on”) but the editing breaks the narrative continuity and turns them into music. This goes past rhythmic editing into percussive editing: the images land with a steady beat (let’s say a tempo of ♩ = 80, moderato) and each one feels like a blow. (Towards the end of this first part, he also breaks the screen into quadrants and begins recapping the entire first part, something I’ve never seen in any other film of his.) Brakhage destroys the narrative order of the original newsreels and creates a new one through a musical technique.

That’s a necessary setup for the second half-hour, where Brakhage shifts to gentler editing and images, mostly of Vienna and of his family camping. The continuity here is closer to narrative, moving through the city or cutting between children just like home movies. He bleeds the two sections together, though: camping shows up in the first part and the newsreels show up in the second. It’s the same structure as in Allan Pettersson’s Sixth Symphony, reversing the order most would make: not the peaceful civilized world breaking down into war, but the peace that overlays war and can’t forget it. It may not be a coincidence that the film itself is dirtier than anything I’ve seen in Brakhage, with misaligned frames, dirt, and wear all over the images. Given how often we see his hand writing, the wear and the camping trip make this feel even more personal, like Brakhage’s reading of Freud, “a man trying to save his own life.” 23rd Psalm Branch moves from war to peace, the world to family, and music to narrative. The end of the film is almost purely narrative and straightforwardly edited, and that’s as it should be, concluding with a superimposed image of the family playing with sparklers. Like the ending of the Pettersson Sixth, it’s a moment of peace and beauty but charged with everything that came before it. Whether it’s respite, denial, or victory, I couldn’t tell you.

More fluidly than 23rd Psalm Branch, For Marilyn (1992) works in the zone between representation and music. (Marilyn was his second wife and curated the second Criterion anthology.) Most of the film is hand-painted frames and the colors seem even more saturated than usual, even faster, and with passages where the colors disappear towards black. Through all this, though, Brakhage layers the colors over and cuts in images of windows, crosses, and churches, like the backgrounds of The Dante Quartet but much clearer. He also cuts in passages of words (“I AM,” then “here,” which quickly becomes “where”; “Mother”/”Church”) and then the words dissolve into the flash floods of colors. The same effect of a clear meaning that presents and disappears occurs in 23rd Psalm Branch by different means; there, words were cut off by the frame or obscured by Brakhage’s hand. For Marilyn presents in three ways, each of which dissolves into the others: the prayer of the words, the music of the colors, the meaning of the images. Like Yggdrasil, Brakhage’s talent has grown over time to the point where can move more subtly and therefore powerfully between those three, managing densities and speeds that he couldn’t do before. In the final minute, the prayer concludes with the words “Thanks be to God” and we see the fastest, widest range of colors and textures yet, a Brakhagian vision of heaven that outdoes The Dante Quartet and calls up the end of The Last Temptation of Christ.

Most of Brakhage’s films are silent; he felt that a score would destroy the continuity of the images and replace it with that of the music. In the few films where Brakhage actually incorporates music, it never overwhelms the images but plays in counterpoint to them. Crack Glass Eulogy (1992) takes night images of a city (usually seen from the air) and adds Rich Corrigan’s Requiem as the soundtrack. Corrigan uses nearly pure synthesizer tones, deployed sparingly, and the images are equally spare, silver lights of reflections occasionally shining out from a barely perceptible landscape of dark structures. Brakhage edits at a much slower, conventional pace here, with only a brief moment of quick images, and the music comes in a while after the beginning of the film and leaves well before the end. A longer, denser work from the following year, Boulder Blues and Pearls and. . ., uses more of Requiem, with material that’s closer to noise, and another Corrigan work for percussion, and overlays more intimate cityscapes with painted frames. There’s more going on here, visually, sonically, and musically–and those last two terms are not synonyms. When we see a shot of of deep blue water rippling in a pond, it feels wonderfully conventional, relieving, like the C major chord that Penderecki finishes his noisy piece for string orchestra, Polymorphia. Structurally, Crack Glass Eulogy feels like a prelude or nocturne to the more extensive working of Boulder Blues. Another work, “. . .” (Reel Five) (1998) uses James Tenney’s Flocking (for piano) for music, and this reverses the structure of Crack Glass Eulogy: the film starts with two minutes of blackness while the music plays. (Fun fact: Tenney himself appears in several Brakhage films, including Cat’s Cradle.) Visually, “. . .” (Reel Five) consists of flickering, hand-scratched frames, edited quickly, much more quickly than anything in Crack Glass Eulogy. Musically, Flocking plays as clouds of staccato notes, the kind of thing that sounds random but has to be carefully composed to work. Just as Crack Glass Eulogy feels dark, spare, quiet, “. . .” (Reel Five) has an abundance of energy and speed in the music and the image. Although in all three films the music has a similar feel, pace, and density to the images, at no point in either does the music line up with the images like a conventional score. Just as Brakhage’s films can best be understood as music, the music in his films can best be understood in terms of images: the music is one more layer, superimposed on all the others, present and part of the experience but not dominating.

Music does dominate I. . .Dreaming (1988), a more conventional work and a compelling one. Joel Haertling took old recordings of Stephen Foster songs and cut them up to create the soundtrack here, and it plays for almost the entire film, only cutting out with an audio splice a few seconds before the end. That sets the tone and the continuity for everything, and Brakhage sets the images to match the music. Foster’s music is in his most melancholy mode here, piano and a lone female voice joined at moments by a chorus, and the words are all those of loss and winding down: “lonely,” “dying,” “fear.” Heartling’s editing keeps the songs from developing full lines and makes us hear primarily the words and the tone, and Brakhage often overlays the images with these words. For the images, he films himself and his family (his grandchildren?) separately: he is slow, moving with effort, usually in the act of sitting or lying down; they are playing, running around, often filmed in fast motion. (The plot here is “Stan Brakhage takes a nap while his grandkids play downstairs.”) The soundtrack, by its pace and sound and words, pulls these images into coherence in a way that Brakhage deliberately avoids in other films. I. . .Dreaming becomes a Stephen Foster-like lament, Brakhage adapting the work of another into his own style, his No Country for Old Men or Barry Lyndon.

Being merciful, it seems to me, is the only good idea we have received so far. Perhaps we will get another idea that good by and by–and then we will have two good ideas. . . .I have often wondered what music is and why we love it so. It may be that music is that second good idea’s being born. (Kurt Vonnegut, Palm Sunday)

I can make some guesses about what that second good idea might be. Just as mercy understands our dependence on each other that goes beyond domination, music understands time better than any other art, better than we understand it. Time undermines all forms, all stability; wait long enough and nothing is as it was. With music, there are no objects. You can reduce music to a finite collection of notes just as you can reduce Brakhage to a finite collection of frames, yes, but neither of those are the music or the films. Music and Brakhage’s films both describe continual transformation, even in something as simple as The Wold-Shadow. They are both realms where the idea of “is” doesn’t apply; they are realms not of Being but of kinesis, motion with a much broader application than objects moving through space. The second great idea may do away with “is,” and if it does, we’ll recognize that it applies to Brakhage’s films as much as to music.

Although I’ve cited a lot of composers and compositions here, it’s Iannis Xenakis who has the strongest kinship to Brakhage. Superficially, both of them went very much their own way and created a unique universe; both of them had a deep grounding in classical ideas and literature. The essential unity with them, though, was the idea of continual transformation. Brakhage’s was visual, intuitive, emotional; Xenakis’ was rigorous and literally mathematical. What both of them did was to take their raw materials–light or sound–and subject it to continual change over a period of time. (Both of them intruded in the other’s realm, with Brakhage occasionally using music and Xenakis designing light-shows according to the same principles as his music.) Their transformations followed a logic that wasn’t always apparent but was never less than compelling, never less than a truly created thing. Watch The Dante Quartet or listen to Eonta: something new has come into the world.

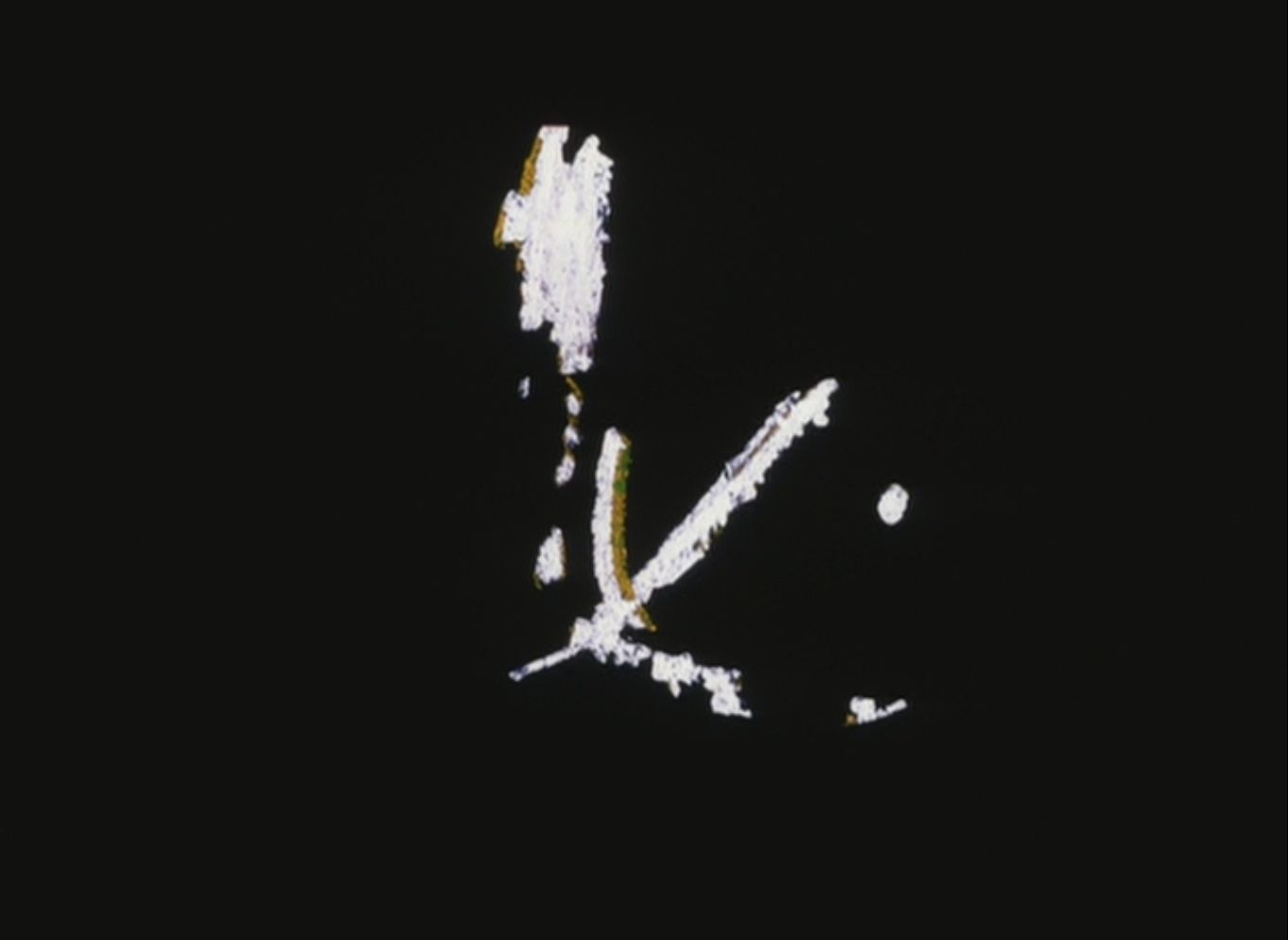

Brakhage died in 2003. He said once that if he was stuck on an island, he’d find flat rocks and chip pictures into them and line them up, and his last film, Chinese Series, comes close to that. (I’ve never known, personally or historically, any artist for whom creating was a choice rather than a necessity.) Dying of cancer that he probably contracted from painting his films with coal-tar dyes, lying in a hospital bed, he took 35mm film and scratched it with his fingernails, leaving clear spaces for the projector “to allow light into what had been Nothing,” and into our eyes. The marks feel almost ideographic, almost like characters; they are made by the response of celluloid to pressure, so the shape isn’t completely under Brakhage’s control: they have a slight greening or browning at the edges, a slight curve of the fingernail. (Robert Rauschenberg called painting “a collaboration with the materials”; so is this.) As a film, these images come in quick runs, punctuated by blackness: brief, isolated, musical phrases. All the frames are first printed twice, then once, so the two minutes of the Series runs slow then fast, the Baroque AA’ structure. Knowing that this is his final work, Chinese Series becomes so poignant, the few scratches asserting themselves against darkness, Brakhage’s last journey through time and with light, until the last frame, until the light is gone, until he fell silent, and time shall be no more.