The last words of Anton Chekhov before he died were what? You remember? He said “Ich sterbe,” that is, “I’m dying.” And later he added, “Pour me some champagne.” And only then did he die. (79)

Poor Venichka is drunk again. All he wants in the world is to get himself on the train from Moscow to the suburb of Petushki, “where the jasmine never loses its bloom and the birds never stop singing,” to spend some time with his dearest and to give a small gift to her little boy, but … look, while we have some time to spare, it wouldn’t hurt to take the edge off a bit, a little hair of the dog to keep him steady on his way? Sure, the angels keep warning him what’ll happen, but the thing about drunks is, they never quite listen.

Even taken at face value, the slim but propulsive Moscow-Petushki is funny and exasperating and horrifying and charming as hell even at its most despairing. It’s the ultimate raconteur novel (in Russian: skaz), the equivalent of spending your commute next to a yarn-spinner whose stories veer from plausible to fantastical and back, who keeps digressing into stories more interesting than the one that already hooked you, who shows you pictures and shares recipes before you realize that, goddammit, you missed your stop.

This isn’t just Drunk History: Brezhnev-Era Edition: Venichka’s train ride is every bit as fantastical and unexpected as the Odyssey itself, a funhouse mirror of the Soviet 70s warped into a tragicomic monologue by a foul-mouthed, poetry-reciting drunk. Let’s join him, shall we?

Before we begin, some quick background on the literary heritage here. Even people largely unfamiliar with Russian literature are likely to have a sense of what academics jokingly call the “Tolstoyevsky” tradition, those heavy tomes of 19th-century psychological-philosophical literature, a tradition that continued in many of the best-known 20th-century works (Sholokhov’s Quiet Flows the Don, Grossman’s Life and Fate, the doorstops of Ayn Rand, etc.) Many readers also know what we might call the miniaturist tradition, that is, small-scale but achingly precise in language and aesthetic effect, a tradition that stretches from Pushkin through Chekhov and even expanded into novel length in the works of Nabokov. More people should know the comic tradition, which was especially rich in the twentieth century, given folks like Teffi, Zoshchenko, and the duo of Il’f and Petrov.

But my favorite thread of Russian literature is the nightmare, the Gothic grotesque with its own pedigree, from Pushkin’s The Bronze Horseman and Gogol’s, well, everything to Dostoevsky’s horrorshow “Bobok,” from Bely’s revolutionary hell of Petersburg (my favorite Russian novel) to Sologub’s provincial hell of The Petty Demon, from the unpublishable fantasies of Bulgakov to the (until recently) unknown Kafkaesque hells of Krzhizhanovsky, until we arrive in their late Soviet embodiment in the form of Venedikt Erofeev himself. In many ways, his voyage to Petushki is the culmination of that tradition in its most modern urban form.

Grotesque times call for grotesque writers. Some older Russians (not without reason) look back on the Brezhnev 70s as an era of relative stability, but the ideological life of the state was never more aimless. The foundations of Marxism-Leninism had been badly wounded by Stalin, and Khrushchev’s attempt at resuscitation lasted barely a decade before disillusionment set in. The Brezhnev era kept halfheartedly voicing the promise of a better tomorrow even while the country’s economic, political, and social life spiraled sluggishly around an endless present. No wonder that high rates of alcoholism persisted despite intermittent teetotaling efforts by the state.

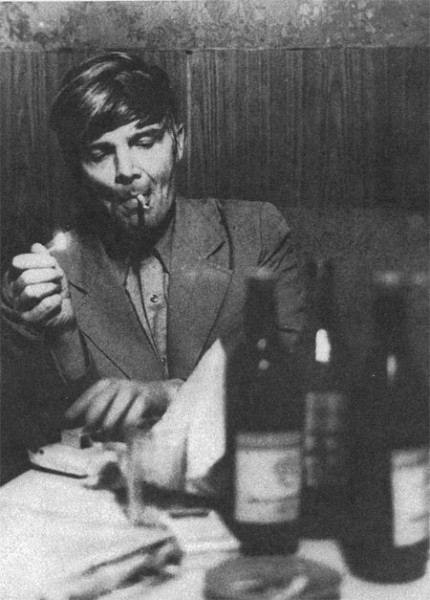

Like a one-man rebuke to the era, Venedikt Erofeev was a modern poète maudit and it eventually killed him. He was born above the Arctic Circle, his father a victim of Stalin’s purges. Booted from the university, wandering listlessly from job to job, he channeled his capacious knowledge into a handful of short, often satirical, mostly unpublishable works. Only Moscow-Petushki is widely read outside of Russia today, though I’d also highlight his essay on his spiritual ancestor, the great philosopher Vasily Rozanov, and his commentary-through-quotation “My Little Leniniana” (which reads like a David Markson novel avant la lettre), both sadly untranslated as yet. At his death at 51 from throat cancer, he left behind an equal number of unfinished works.

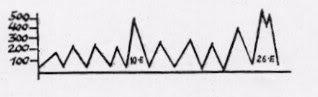

Moscow-Petushki has elements of memoir — the main character not only shares the author’s name, but also his occupation and habits — but its reality is slippery in all the best ways. The book’s Venichka is a vagrant, fired from his job as a foreman for graphing out his and his colleagues’ alcohol consumption at work:

All the workdays of the previous month were indicated sequentially on the horizontal axis, the amount of alcohol consumed — calculated on the basis of degree of proof — on the vertical axis. Of course, only whatever was consumed on the job or before was tabulated, since the amount consumed in the evening remained relatively constant, and was, therefore, of little interest to a serious researcher. (38)

Today, Venichka is drawn to the siren’s call of Petushki, rousing himself from the streets of Moscow (where, he repeatedly tells us, he has somehow never seen the Kremlin), steeling his nerves for the train ride, and bonding with his fellow passengers over drinks, tall tales, and more drinks. They tell stories, they debate, they vomit, they enter and exit the train. His encounters grow more fantastical, more grotesque, as he approaches the end of the line. Throughout, Erofeev fully exploits his novel’s unpublishability by indulging in obscenities that would never have made it past the censor even if the book had been ideologically above board.

In lesser hands, it’s easy to imagine a version of this novel that serves as a facile cautionary tale: Venichka is a vagrant, unwashed, and pathetic, and the reader might well wonder there is anything waiting for him in the earthly paradise of Petushki (in reality, an industrial exurban neighborhood). One passenger even wonders aloud if the Russian tragedy is that alcoholism and despair go hand-in-hand: a country despairing so long, and for so many reasons, cannot be expected to greet each morning sober. But while Moscow-Petushki makes no compromises about the horrors of aggressive alcoholism, it also doesn’t ask for or expect our pity: it blows a defiant raspberry at tragedy, a novel that keeps us laughing even when describing the world of derelict boozers:

I remember ten years ago I moved to Orokhovo-Zuevo. At the same time, there were four other people living in the same room. I was the fifth. We lived in complete harmony, and there weren’t any quarrels among us. If someone wanted to drink port, he would get up and say, “Boys, I want to drink port.” And everyone would say, “Good, drink port. We’ll drink port with you.” (30)

Venichka treats his alcoholism like a sacrament: this is a blasphemous novel that somehow seems more genuinely religious because of it. He negotiates with angels about the best place to grab the cheapest alcohol. He despairs that the piss-water beer on the train is too profane for the heights of religious ecstasy required by the holy act of drunkenness. The book is packed with Biblical references (Christ’s command to the sick girl, “Talitha cumi!”, is a repeated refrain), maintaining a reverential tone that’s not quite serious but also not quite mock-serious:

Drink more, eat less. This is the best method of avoiding self-conceit and superficial atheism. Take a look at a hiccuping atheist: he is distracted and dark of visage, he suffers and he is ugly. Turn away from him, spit, and look at me when I begin to hiccup: a believer in overcoming who is without any thought of rebellion, I believe in the fact that He is good and therefore I myself am good. (65-6)

The alcohol jokes throughout are both funny and serious. Take the book’s most (in)famous sequence, where Venichka regales us with his own special cocktail recipes, like “Bitch’s Bastard”:

- Zhiguli Beer (100g)

- Sadko brand shampoo (30g)

- scalp treatment for dandruff (70g)

- foot antiperspirant (30g)

- insecticide for small bugs (20g)

Funny and horrifying all at once, maybe? But also not quite fantastical, given the ways that various Soviet-era attempts at prohibition (mostly aimed at spirits like vodka, which only drove sales of equally dangerous fortified wines) led the most committed alcoholics to drink anything they could get their hands on. As Venichka slurs his way through his story, it’s hard not to wonder what else is coursing through his system, and who exactly the angels are that keep him company:

The rest of the Kubanskaya [vodka] was still seething somewhere not far from my throat, so when the words Why did you drink it all, Venya? That’s too much came from heaven, I was hardly able to breathe out in response: “In the whole world… in the whole world all the way from Moscow to Petushki there has never been anything like ‘too much’ for me. …And why are you fearful for me, heavenly angels?”

We fear that you’re going…

“That I’m going to start swearing again? Oh, no, no, I simply didn’t know that you were with me constantly or I wouldn’t have before, either. … Minute by minute I’m getting happier and if I start to get foul-mouthed, it’s only because I’m happy. How silly you are.” (48)

What helps this all go down smoothly (so to speak) is that, rather than a grind into unbearable realism, this is an intensely literary novel: that is, Erofeev constructs his pseudo-memoir from the detritus of other literatures, sometimes satirically distorted, but always purposeful. The book’s subtitle, “A Poem,” is a wink to Gogol’s Dead Souls. Venichka, whose narration swerves from medieval histories to classic literature to modern Orthodoxy, is well aware that his train journey represents a literary genre, albeit one hacked into pastiche: “All the way from Moscow it was memoirs and philosophical essays, it was all poems in prose, as with Ivan Turgenev. Now the detective story begins.” (73) When Venichka imagines the giant statue of the hammer-yielding worker and the sickle-yielding peasant stomping over to smack him around (in the head and the balls, respectively), it’s not just a funny and pointed bit of political satire, but also a slapstick reconfiguration of famous literary nightmares (Pushkin’s in The Bronze Horseman, Bely’s in Petersburg), a kind of highbrow low comedy.

Venichka is a medieval Holy Fool, a Gogolian gargoyle, a Dostoevskyian buffoon, and in his eternal torments he cries out from the abyss for a perfect world just beyond our reach, be it Petushki or otherwise. That he resonated so strongly with readers in the Brezhnev years, and that he continues to resonate with contemporary readers, says just as much about the grotesqueness of our own world so precisely and depressingly diagnosed by Erofeev. But we might as well raise a toast, since the ending, after all, is the same for all of us:

And if I die sometime — I’m going to die very soon — I know I’ll die as I am, without accepting this world, perceiving it close up and far away, inside and out, perceiving but not accepting it. I’ll die and He will ask me: “Was it good there for you? Was it bad there for you?” I will be silent, with lowered eyes. I’ll be silent with that muteness familiar to everyone who knows the outcome of days of hard boozing. For isn’t the life of man a momentary booziness of the soul? (154-5)

NOTES

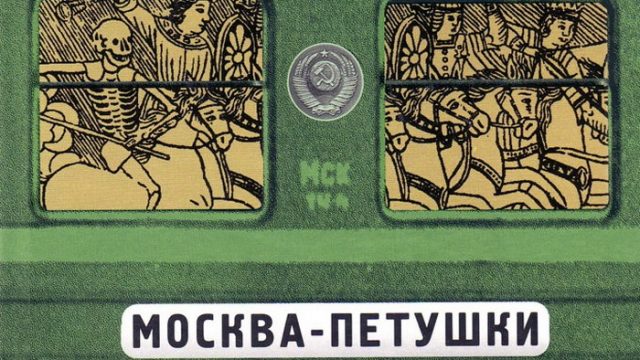

- To be fair, Moscow-Petushki was written and widely read before 1973, but it qualifies for this Year of the Month because it wasn’t officially published until ’73, and even then, published abroad and for foreign readers. Like so many other great works of Soviet-era literature, its zealous fans spent the 70s creating and disseminating samizdat copies, faithfully re-typed with carbon paper, glued into non-descript or misleading book covers, and surreptitiously passed among family and friends. Here’s an example of Moscow-Petushki from 1981 (when the book was still banned in the Soviet Union).

- Moscow-Petushki’s monologic form makes it ideal for theater, and it has been staged dozens of times, but there is also a film: director Paweł Pawlikowski — yes, the very same who recently won an Oscar for his film Ida — put together a short video-essay of sorts for BBC television that not only dramatizes scenes from the novel, but also includes interviews with Erofeev himself. By this point Erofeev had had part of his throat removed and could only communicate through a voicebox. Segments of the novel are read in English by actor Bernard Hill, the future King Théoden. At only 40 minutes, it is well worth your time even if you haven’t read the novel yet.

- Of course there is a monument to the novel in Moscow. One side depicts Venichka with an epigraph from the novel, “Never trust the opinion of someone who hasn’t managed to get some hair of the dog in him.” The other side depicts Venichka’s beloved in Petushki with the line about jasmine and birds.

- Book quotations not translated by me come from the H. William Tjalsma edition, Moscow to the End of the Line (with page numbers in parentheses). Highly recommended. My badass featured image is from the 2000 Vagrius edition. More cool editions of the book here.