W.R. Burnett’s original 1929 novel Little Caesar opens with a quote from Machiavelli. The 1931 film version opens with a quote from Jesus Christ.

Those two threads of morality and amorality will continue to weave throughout the history of the American gangster movie, and are particularly notable in the earliest landmark works of the genre. On the one hand there is the cold, pragmatic recognition of the hardness of the world. On the other is the striving idealism and condemnation.

“The first law of every being,” as Machiavelli is quoted in the novel, “is to preserve itself and live. You sow hemlock, and expect to see ears of corn ripen.”

How far indeed, will a man go to survive? How far will a gangster go to preserve himself and live? The earliest of the true gangster classics are all deeply concerned with this question, and their understanding — on some level — of the gangster’s plight will naturally brush up against the limitations imposed by societal values, as embodied by the New Testament’s teaching that those who live by the sword will die by the sword.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Because before there was a Little Caesar, there was a Snapper Kid.

In 1912, when D.W. Griffith and his Biograph Film Company shot The Musketeers of Pig Alley, little of the trappings or markers of gangsterism (as we now know them) were in existence. This was before the Great Depression — hell, it was before the Great War. Nationwide prohibition of alcohol was still eight years away and the Thompson submachine gun was nine years away from being commercially available. In all but the most hip and hep corners of New Orleans, jazz was an unknown quantity, and ragtime records (without the benefit of the radio) ruled the day.

And the movies were in their infancy. Features were still extremely rare. American film production was mostly based out of New York and New Jersey. The sleepy little town of Hollywood, California had just rescinded its ban on movie theatres.

Kentucky-born actor turned director David Wark Griffith might have seemed like an unlikely individual to be the midwife of the gangster genre, and the truth is that he didn’t entirely succeed. But the seeds of the genre are there, 19 whole years before Edward G. Robinson would swagger his way onto American movie screens.

The Musketeers of Pig Alley is brief little melodrama, around 16 minutes long, about a young couple who get accidentally wrapped up in the world of New York’s criminal underground. Griffith’s old-fashioned (even for 1912) Victorian moralism is an odd match with the gritty, hardboiled world of the gangster, and the film doesn’t quite come together in the way that it should, but it contains some very nice moments, all of which center around the character of “the Snapper Kid” and his gang, who is far more interesting than the picture perfect lovers who are meant as the story’s sentimentalist heroes.

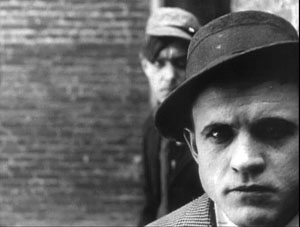

The Snapper Kid (Elmer Booth) is introduced almost diabolically — from a doorway come several puffs of cigarette smoke, heralding the entrance of the fiery young hoodlum as though he were Mephistopheles. He promptly steals the wallet of a naive young musician and makes off with his ill-gotten gains.

The Snapper Kid is one of those pre-Prohibition, pre-Arnold Rothstein crooks whose time seems to be consist entirely of mugging dumb tourists and getting into fruitless gunfights with the police around conveniently-placed barrels. Booth plays him with a nice bit of swagger and bluster, though he in fact seems a lot less intimidating than the other members of his gang.

But what Griffith and his co-writer Anita Loos do with the Snapper Kid will pave the way in many respects for future silver screen gangsters: they develop a soft spot for him. The plot of The Musketeers of Pig Alley thickens when Lillian Gish, as “the Little Lady” (Griffith, you fucking Victorian, you) who is married to the hapless young musician goes off in search of the man’s missing wallet. She winds up in what the titles call “New York’s Other Side”: the overpopulated, dingy back alleys where men drunkenly waltz by with large jugs of liquor in their hands, and to the saloons and dance-halls where gangster cavort with their molls. The Little Lady is almost drugged by a rival gang leader, but is prevented from doing so by the Snapper Kid. When Snapper later gets in a shootout with the rival gang, and the police come looking for him, he is protected and given an alibi by the grateful Little Lady and her Dumb Young Husband, who has found his wallet. A happy ending for all, it would seem.

The ending is quite pat, honestly, but what it evidences is something that this author discussed with the excellent fellow Soluter Grant “Wallflower” Nebel, that much of what goes on in gangster movies is concerning moral choices in a system that exists outside the law. With this film, Griffith can illustrate that a man can be a killer, a thug, and thief, and a gangster, while still being “good” enough to deserve the protection of the saintly young married couple from the representatives of law and order. Of course, by doing so, Griffith is also showing that a seemingly perfect pair of lovebirds can also become soiled by the grey morality of that world of gangsterism, but the film ends before those implications can be further explored.

The Musketeers of Pig Alley is not quite a gangster film. Something in the genre is still unformed, but Pig Alley is the primordial ooze from which the rest of our big city cavemen will emerge. Like one particularly great shot in Griffith’s film, the Gangster was coming closer and closer, peering into our eyes with both a hunger and kinship.

*****

Caesar Enrico Bandello. Rico. Little Caesar.

Emanuel Goldenberg. Edward G. Robinson.

Hollywood’s first iconic gangster was a man of many names and one great desire in life.

From the beginning of 1931’s Little Caesar (directed by Mervyn LeRoy), we get the sense of the hunger that lurks within Rico Bandello. Having just robbed a gas station and killed the proprietor, Rico settles into a late night roadside diner for a midnight snack, sneakily setting back the diner’s clock a few hours to give himself an alibi. He scans a newspaper with his pal Joe Massara (Douglas Fairbanks Jr.) and remarks that the only way to do things “in a big way” is in the big town, and decides to head out for Chicago to make his name, dragging Joe along with him.

Rico, just a small-time stick up guy at first, talks his way into the company of mobster Sam Vettori, a tough guy who owns the Palermo Club and runs a gang of robbers with names like Killer Peppi, Kid Bean and, my personal favorite, Scabby. Little Caesar plays an important role in establishing the big city, and the gangster world, as a complicated and dense web of organized criminals of different kids, sometimes allied and sometimes competing with each other — a Wall Street of Felons, as organized and hierarchical as a bank or brokerage. Vettori works under the slickly-dressed “Diamond” Pete Montana, who runs the North Side and maintains an uneasy truce with his rival Little Arnie Lorch. But all of them — Rico, Sam, Diamond Pete, Little Arnie — are subservient to the “Big Boy,” a mysterious figure who is politically connected and refuses to be photographed or publicized. The Big Boy makes things happen in Chicago. And that’s who Rico wants to be.

Over the course of what seems to be only a few weeks, Rico kills the city’s crusading crime commissioner, bullies Sam Vettori out of the gang leader’s chair, gets his picture on the front page of the newspaper, scares Little Arnie out of town, and makes himself into a wealthy man with the fine, fancy suits to show for it. The Big Boy nixes Diamond Pete and gives Rico the keys to the North Side, but even that doesn’t satisfy Little Caesar’s hunger. No sooner than he has been promoted by the Big Boy does Rico begin making comments about wanting to be “the Big Boy” himself.

What Rico burns with that simple, animalistic survival principle that Machiavelli wrote of. The rest of the gangs in town have a policy of doing as little violence as possible, in order to minimize risk and avoid unwanted headlines. But if Rico sees someone as a threat, whether they’re a gas station attendant or the city crime commissioner, he will shut them down. Forever. Even if this muddles the organization’s plans.

Rico Bandello despises weakness and cowardice, mocking those older gangsters who “can dish it out but can’t take it.” He kills members of his own gang when he’s worried that they’ll rat on him, even gunning down one guilt-ridden young getaway driver on the steps of a church, and then showing up to his funeral with the biggest memorial wreath of the entire gang. He seems to feel no compunction about this whatsoever.

But when Rico’s best friend Joe, who has gone straight and become a dancer, is in a position to reveal crucial info about Rico to the cops, Rico prepares to kill him, yet finds that he can’t. This decision leads to the unraveling of Rico’s life on the top. In a matter of months, Rico finds himself drunk and penniless in a flophouse, alone in a corner while a trio of hobos read a newspaper article about the downfall of the great “Little Caesar.” Rico impulsively calls the police in a fit of hubris, and tells them that he will prove to them that he is not “yella,” storming out of the flophouse, determined to be the old Little Caesar again.

Of course, the cops have traced the call and ambush Rico, annihilating him with a barrage of machine gun fire. The dying Rico manages to gloat to the cops that they never got their cuffs on him, before sadly turning to the night sky and with his dying breath, murmuring “Mother of mercy, is this the end of Rico?”

It is.

What is crucially different about Little Caesar in comparison to the earlier movie is that in Little Caesar, the sentimentality provides not a happy ending, but a downfall. While the Snapper Kid can save a pretty young window and then be granted a phoney alibi by a happy couple, it is Rico’s inability to be absolutely brutal and kills his own best friend that causes the dismantling of his criminal empire. His goal was to survive, to sow the hemlock, and yet he couldn’t do it — he allowed himself few emotional attachments in the world, but it only took one to lead to the end of Rico.

So what does this mean? Is the film advocating Machiavelli’s survival-at-any-cost maxim, or promoting the idea of “live by the sword, die by the sword”? Or is the answer somewhere in between, somewhere beyond that? Or did Warner Brothers and Mervyn LeRoy want nothing more than to entertain audiences with some Tommy Gun vaudeville for a 75 minutes?

The answer, I think, is that the gangster film, more than any other genre of film, recognizes the inherent harshness of the world, that holds to a law that is unreachable and obscure, where bestial actions can both benefit you and destroy you, and only the most wise can recognize which choice is the right one from where one is standing.

Little Caesar was not that man.

Most of the gangsters of this first Classic Period of Gangster Movies are not that wise man either. For them, the end of Rico will be repeated again and again until we’ve watched Edward G. Robinson dead more times than we’ve seen him alive. Rico can set back the clock in a roadside diner, but he cannot prolong his short, nasty, and brutish time on the mean streets of the Chicago — or, for that matter, Hollywood.

*****

American Underworld will continue next time with a look at other classic gangster films of the pre-Code period of 1930 to 1933 or so, including The Public Enemy and the original Scarface. Feel free to comment then and now.