One of the surprising wins at this year’s Oscar ceremony was Alex Garland’s Ex Machina taking home the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects in a category that already had two powerhouses: Mad Max: Fury Road (which had rightfully swept up nearly all the technical awards) and Star Wars: The Force Awakens. This win was only a blip on the radar in the post-Oscars discussion but the film was heavily rewarded with insightful dissection over a year ago when the film was released. Upon re-thinking its merits, of which there are many, I’ve been reminded of a constant internal discussion I’ve had with myself during this decade regarding the state of the science-fiction thriller.

There is a small forming sub-genre here that I’m going to dub Kubric-Lite; in which the following films all achieve similar tones and aesthetics that match that of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and to various extents explore that film’s themes: existentialism, human evolution, technology, artificial intelligence, and extraterrestrial life. The three films that invoke these qualities are 2010’s Beyond the Black Rainbow, 2014’s Under the Skin, and now last year’s Ex Machina. Allow me to propose a marathon, and the order in which you should watch these films and why.

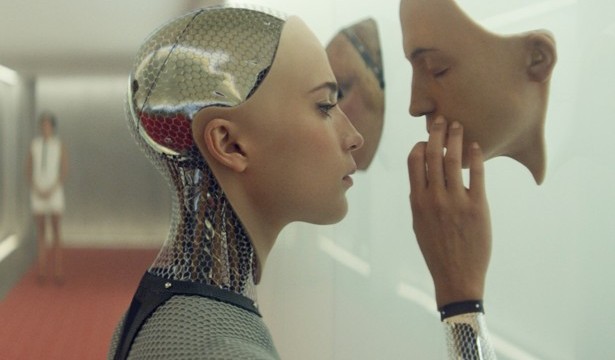

- Ex Machina: In all honesty despite the accolades and the shiny Oscar, I personally find this to be the weakest of the three films by a fair margin. Its fault being that it is the newest one and therein proving to be less ambitious than the other two movies. By that I mean this film feels rather safe within its parameters, never reaching the highest of highs that are found in Under the Skin‘s horrific minimalist visuals or the lowest of low’s as in Beyond the Black Rainbow‘s out of nowhere turn into a slasher film in it’s final moments. Ex Machina is the most polished of the three, with the most coherent and articulated script, crisp and clean modernist architecture and design that is the utmost realization of 2010s that science fiction of the past could not possibly have foreseen, and two outstanding performances from Alicia Vikander and Oscar Isaac.

This is the film that hits nearly all of the themes in for Kubrick-Lite, wherein the characters themselves are devoted to discovering and talking about how humanized and driven artificial life can go ala the Turing Test. The film is meant to be psychologically manipulating to the viewer and to Domhnall Gleeson’s “beta male” character who slowly begins to unravel how incredibly insignificant he is in his role of the film on a contextual and subtextual level. We’re to believe he is the hero who will save Vikander’s Ava, and he believes this too, but truly only Ava knows how everything is going to play out and that’s the undoing of both men in the film. Film Crit Hulk wrote a piece about the feminist interpretation of the film, in which he suggests in his essay that the film is an allegory for the dissonance between men and women; in other words, that men do not see women as their equals. The film reaches its breaking point when Gleeson’s character begins to doubt his own humanity in the film’s most disturbing sequence involving a razor and an icy cold stare in the cabinet mirror of a bathroom. As we’re going to see with each of the films, this is the apex and devolution into classic film narrative, where I believe the film fails to follow through on the darker impulses that have been laid out.

Considering Film Crit Hulk’s argument, the spiraling of Gleeson and Isaac’s mental state at this point should have embarked on a manic frenzy not unlike the climax of 1980’s exploitation film Maniac. Similarly a film that explores the savagery and brutality of enforcing a form of sexual discipline on women, (albeit with more head explosions), Maniac ends with the titular Maniac being literally physically, mentally, and psychologically devoured by that of which he has caused. The idea is there in the conclusion of Ex Machina, but it opts for understated ambiguity which makes it feel like it’s choosing the safer way to conclude this story. This makes Ex Machina the easiest to digest and therefore a perfect starting point on our Kubrick-Lite journey.

- Beyond the Black Rainbow: This graduates from Ex Machina‘s layouts of how a Kubrick-Lite movie wants to be written as cold and intellectual to how a Kubrick-Lite movie visually is cold and intellectual. We’re no longer taking one hit off our roommate’s blunt on a Wednesday night and talking about systematic oppression man, we’re now knee-deep in an acid trip talking about our relativity to the alignments of Jupiter on the roof of a van with stars in our eyes and our pants left behind in the 7/11 bathroom sink. Its psychedelic, its hypnotic, its design is monochromatic and geometric, and it harkens so far into the acid lucidity of the late 70s and early 80s that it’s even set in the 1980s. It even has a kick-ass Tangerine Dream-inspired soundtrack. It is so close to being a perfect movie. But it is a movie that expects patience from you and, as mentioned, unfortunately belly-flops on the landing.

Beyond the Black Rainbow is weird, and if Ex Machina satisfied your need for science fiction abstraction, you might not have the patience for this film’s grinding slow pacing. Personally speaking, the former film is just the warm up, where here the indulgence of the aesthetic and sound design paint this fascinating world that is so bizarre and out there that its mute protagonist Elena doesn’t need to espouse why everything around her is so unusual, it’s the only world she knows. There is no Gleeson character equivalent here, Elena is alone in this institution that torments and exploits her and honestly does a better job of humanizing her with her understated performance and fragile demeanor than that of Ava. However the intentions here aren’t the same, Elena isn’t aware of her extraordinary abilities, she only has fragments of clarity and understanding of who she is and the isolation she exists in. The key difference in the film’s conclusion here as opposed to Ex Machina‘s is that Ava’s escape is ultimately a reflection of Gleeson and Isaac and their manipulations of their roles as men of intellect and sexual power, whereas Elena’s escape is about personal freedom and identification. Elena barely has an identity throughout the film but her tears and facial expressions suggest a childish need for companionship and humility, the kind that Ava only feigned to have.

The film’s antagonist Barry Nyle is obsessed with Elena for everything he is not; her physicality, her abilities, her humanity, all of which Barry literally sheds throughout the feature. Barry has given himself to this surreal science only to be destroyed by it, while Elena was created from it. It is interesting though that this is another film that positions men of power over helpless young women, but the intentions of which seem more hopeful here. There’s a basic good versus evil setup between the two, a form of the Freddy Krueger/Nancy Thompson dynamic where the former underestimates the latter’s ability to match and overcome the psychological manipulations that they face. It is also seen how the main set location, the Arboria Institute, is the culmination of abstraction and scientific extremism in an otherwise normal universe. Barry Nyle is beyond normalcy whereas Elena simply wants to find it. She still has the chance which makes her the most hopeful and innocent of our Kubrick-Lite leading ladies, something that will also factor in heavily with Under the Skin.

Out of the three films here, it’s Rainbow‘s conclusion that falls prey to the devolution into classic film narrative the hardest, to the point where you can almost feel the Screenwriting 101 professor place his hand on writer Panos Cosmatos’ shoulder and say, “That’s enough weirdness, let’s pull back now.” In narrative structure, the peak of rising action is the climax which devolves into falling action and then flattens into the denouement. In this film’s case it certainly feels like the absurdity was suddenly yanked back on a leash to introduce a more “normal” ending as opposed to going full bonkers. Needless to say, asking a film as quiet and slow as Beyond the Black Rainbow to engage in complete lunacy is already asking a lot when you have a chase seen involving the Sentionaut and what he actually looks like underneath his rad helmet. However having the conclusion of Elena and Barry’s confrontation take place in the institution makes more sense than having Barry go all Jason Voorhees on a couple of guys on their way to audition for American Movie: The Wonder Years. That being said the final moments of Rainbow invoke a sense of hope for our protagonist as opposed to the other films, and even leaves the audience wondering how a character like Elena could even thrive in society after her experience. Our final film, Under the Skin, will offer its own variation to that question.

- Under the Skin: This is the only movie that hits the Kubrick-Lite theme of extraterrestrialism head-on, offering us a character who is not part of our world and does not belong on our world. Elena was a sheltered and emotionally crippled human, Ava was a cyborg who understood humans better than they understood themselves, whereas our protagonist here is so stripped of emotions that she is never even given a name. She is simply The Woman. Scarlett Johansson’s Woman is the embodiment of cold and intellectual, the constant that is found often describing Stanley Kubrick himself and his tone in films. By watching her interact with other unaware humans, of which the former two films do not share the opportunity, the detachment only amplifies how inhuman and alien she truly is. Added by the eerie string music and her fellow soulless companion the Motorcyclist, there is only the haunting idea of what a woman is here and no affirmation that there ever could be a human underneath.

The common complaint I have with so many movies, specifically genre films, is the lack of being dark and weird. This again falls back into the devolution into classic film narrative, where we can’t get too dark and too weird because we’re in Act III now and that means we need to wrap things up instead of keep going with the funky shit. Beyond the Black Rainbow endures in its weirdness but keeps viewers at a distance, whereas Under the Skin is easily the darkest out of all of them. Why is she interesting in harvesting the organs of unsuspecting randy men along the UK coast? Where does she come from? What are the mechanics of those amazing scenes where she sends them into a trance and lures them into the water? What is it about the disfigured man that sparks her interest in humanity and emotions and the absolute tragedy on the beach did not so much as get a second glance from her? There’s so much ambiguity in the film’s first half that leaves a lot of dread for its viewers that any answer that could have been given likely wouldn’t have been satisfactory enough. It’s the turning point in this film where it becomes a different movie. Is that bad? Not necessarily, just different. Whereas I could have endured another full hour of The Woman and the assimilation of humanity at our darkest hour, the shift in tone part way sparks the answers for questions that our former films only ended on.

The second half is an endurance of existentialism, what does it mean to be human in the most literal and basic ways? The Woman engages in sympathy when she encounters the disfigured man, understanding that he, like her is different from everyone else but in a completely different way. Something about their interaction triggers a desire to be normal in this world that she doesn’t understand. The film undercuts these attempts by targeting her anatomy, something that is only a shell and has nothing underneath. There is no desire for food, as seen in the impeccably done “cake eating” scene, and the mechanical instincts of sexual intercourse are only a display when she herself has nothing to actually engage with. The first half of the film spends time with her simply observing, physically blending in but never actually engaging in human life. She is more robotic and lifeless than Ava ever could have been, as she only has one assignment and is only designed for that assignment. Every attempt at human behavior is unobtainable because of her lack of emotional functionality and her physical limitations. She’s as good as those prop computers you see in furniture stores, yes it looks nice but you can’t actually plug it into anything. It’s just a prop.

The other factor of the movie relies on sexual predating, reversing the roles of men and women. Here it’s men walking home alone at night who should be worried, it’s the men who are preyed on in a society that dictates dictates a ridiculous standard on how women should behave and how they should dress and how they should act and how it’s their fault if they’re victimized. When Johansson’s Woman finally allows herself to be vulnerable after spending the movie preying on other’s vulnerability, she is they preyed upon herself. Her final reveal of her true form exposes her at her most vulnerable which makes her the most human she’s been throughout the entire movie.But this is at the cost of her own life, making her a victim and proving to be no more powerful nor even as helpless as her fellow man. Like the rest of us, she simply existed.

So why save this film for last? Because the second half’s devotion to existentialism brings us back down from our high of surrealism and isolation. Under the Skin‘s second half winds down with an appreciation of basic human interaction and fulfillment. Yes maybe we are alone in the world but we’re nothing without the simplicities of life and our need to feel. Stripped away of what makes us unique we all want to be a part of something and be allowed to be vulnerable. It is interesting that in these Kubrick-Lite films, they each revolve around a woman who desires to simply be accepted in society as though women cannot be part of society without male dependency. However if the genders had been reversed, would that make these films any less about human oppression and existential existence? No, I think that by having women lead these films suggest that there’s an evolution in science fiction writing that is expanding on our societal roles. Look back at those films that Ex Machina was in competition with for the Oscar; Mad Max and The Force Awakens were both lauded for their portrayals of women on film, even The Martian treated its female characters as that, characters who were integral to the story not used as a false statement that says “We’ve Put a Token Woman In this Film, We Have Solved Sexism”. Is the oppression still there? Yes, but each of these films have something to say about that which forces them to get dark and weird which is why they should be watched.

When films get dark and weird, that’s when things get interesting.