(Clearly all the Americana aspects of Ives are in the way of sound coming into its own, since sounds by their nature are no more American than they are Egyptian.) (Cage, 1959)

Charles Ives’ influence on American classical music never goes away. He was the country’s first great experimenter in music; he also turned to distinctly American rather than European sources to make music, sprinkling references to hymns, marches, authors, and places all through it. Sometimes these were matters of single melodies and specific people (the “Concord” piano sonata); sometimes he built them up into huge, dissonant, and gloriously messy orchestral works (the “Holidays” and the Fourth symphonies). His most direct musical descendant is Elliott Carter, but John Cage also carried on the Ives legacy in his own way, first turning away from him but later in his career creating the Ivesian Apartment House 1776, which has a claim on being not just the best thing he ever did, but the mythical Great American Symphony.

In his early writings and career, Cage rejected Ives, pursuing what Christian Wolff called “a concern for sound come into its own.” Writing about Ives, he said that what was most interesting in Ives’ compositions was not the references but the “mud” of all the sound happening at once; since no one line of music was identifiable, the mud of all the sounds together became a new sound with no reference to anything that came before. Cage pursued this much more rigorously. In his chance-based method of composing, he first set up the parameters for a composition and then tossed coins to get a number from 1-64 to determine each parameter; the method comes from the I-Ching. (Following the Chinese meaning of the title, “Book of Changes,” Cage’s first major piece written this way was the 1951 Music of Changes.) The goal was to create a music that broke from any continuity and, more importantly, any audience’s expectation of musical continuity. Cage, here, can fit into the modernist tradition because he tried to cut sound away from its cultural assumptions, which is to say from its past.

Cage got less rigorous in his philosophy as his career progressed, although no less rigorous in his composing. (It was only in the 1980s that he began using computers to generate random numbers rather than tossing coins himself.) In particular, he began engaging with the music of the past, importing them into a strain of his compositions via chance. Not all of them were done this way, but in multimedia works from HPSCHD (1969) to the Europeras (1987-91), he let this music be present and recognizable. He allowed the music the function of calling up the past as well as being part of an overall mix.

Apartment House 1776 of 1976 fits neatly into this branch of Cage’s music. As the name and the date imply, it was a commission for the Bicentennial. Following the principle of a lot of Cage’s music, he wanted to create many different musics happening all at once. (Introducing a lecture in his book Silence, he wrote “for I had wanted to say that our experiences, gotten as they are all at once, pass beyond our understanding.”) His first rule: choose music that would have been heard in 1776, and in America–if we want to get picky about it, Northeastern America. He went back to hymn- and drum-books of the time to get it, and used his chance operation to pick some and alter others. The material includes “44 Harmonies, 14 Tunes, 4 Marches, and 2 Imitations,” and also songs for four singers: Protestant, Jewish, Black, and Native American. (Cage allowed live or recorded singers as long as the songs were “authentic”–i.e., from the period.) From this material, performers choose their own program; as with a lot of Cage pieces, this creates a dense and compelling sound mix, something that doesn’t hold together by the older rules of music but works in other ways. (Again, the distinction between the modern and the avant-garde: the former breaks the rules, the latter ignores them.)

The 44 Harmonies reveal a lot about Cage’s methods, and stand on their own as a beautiful work; Irvine Arditti arranged them for his string quartet. His way of using chance never meant “do whatever you want,” it was always about using chance to figure out exact musical details. That meant carefully planning what the chance operations meant: he said composing by chance was a method of asking questions, and if the questions aren’t any good, neither are the answers. For the Harmonies, he took American hymns from the period and tried various ways of randomly altering them: deleting voices, deleting notes. Those didn’t work: in his words, “I got an interesting result from an interesting piece and an uninteresting result from an uninteresting piece.” (Although Cage insisted that chance was a way to get away from his own musical tastes, they always came into play.) What he finally hit on was: use chance to select different notes in different voices, and then delete some notes and extend others. What resulted was music that would “keep its flavor at the same time that it would lose what was so obnoxious to me: its harmonic tonality.”

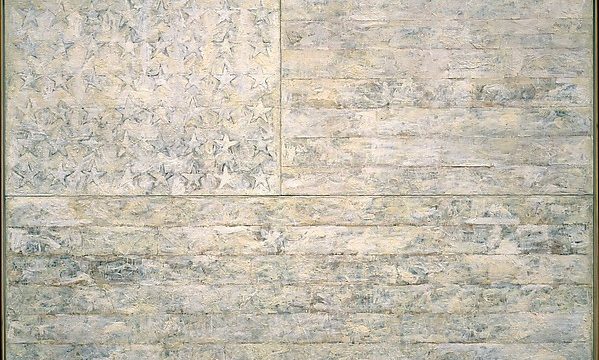

In performance, the Harmonies, played by different instruments, create a rich, alluring, constantly shifting ambient background. The long tones and lack of any harmonic resolution combined with the different timbres of the instruments make it a static tapestry of sound. Morton Feldman’s late orchestral pieces For Samuel Beckett and Coptic Light are like this but they don’t have the historical specificity of the Harmonies. Cage has it right: “you can recognize it as eighteenth-century music.” Brian Eno described ambient music as being like a “tint”; the Harmonies are the musical equivalent of the dark, shaded, subtly colored background of an eighteenth-century painting.

Over that background, the singers and the musicians throw in their own lines. The Marches command attention whenever they show up–the drums are loud in the mix here. (I am using the Mode recording here.) The Imitations are done on violin; they’re fast, dancelike (jiglike really) but have a quality of losing energy as they’re played. They somehow feel like they would have been old in 1776, and that quality of mixing times, of presenting incompatible things as incompatible without trying to make them work together, holds all through the music.

One of the most noticeable and affecting things about Apartment House 1776 is its different cadences, the sense of different directed rhythms. The Harmonies have the cadence stripped out of them, but the different singers have the different intonations of their traditions: the sliding, proto-blues lines of the Black spirituals, the steady iambic beat of Native American chants, the different speech-like rhythms of Protestant and Jewish hymns. It’s something that’s past meaning, and it’s why singing can affect us even when we don’t know the language; here, letting the voices overlap takes our attention off the words and puts it on the melody and sound. Some the best moments come when a single voice comes out of the mix; the Mode recording opens with “There Is a Balm in Gilead,” like an invocation, and “All God’s Chillun Got Wings” commands attention no matter what else is going around it.

Luciano Berio, writing about the middle movement of his Sinfonia, where he mixes Mahler’s Second Symphony and a Beckett text with his own music, said “the experience of ‘not quite hearing’ is conceived as essential to this work.” That’s pretty much the mission statement of collage works like Apartment House 1776. A composition seeks to unify different things in an artistic whole; a collage keeps the disunity, keeps the elements as distinct, disparate things, but shifts our attention between them. Sometimes the elements come clear on their own, sometimes they’re submerged (as the hymns of the Harmonies are), sometimes they are lost in the mix. A musical collage includes the element of time, so the composer (or in this case, the performers) has partial control over where our attention goes.

Cage worked with collage as far back as the Credo in Us of 1942; his Williams Mix, although he called it a collage, mixes sound fragments that are too small to be recognizable–it’s a unified work of noise rather than a musical collage. His sense in these compositions was always playful in both senses: they’re fun and they give a greater degree of freedom as to how we hear the music. In Apartment House 1776, hearing all these fragments against each other makes each one a foreign language to the other. For half an hour, everyone, every singer and player wanders through each other’s churches. Each hymn, harmony, tune, and march becomes no less beautiful or reverential but loses its exclusivity. For a moment, everyone gets to listen to everyone else, and it is good. (A careful strategy here on the part of the performers makes that happen: there never seems to be more than five lines of music going on at once, and again, there’s close attention to how the voices move in and out of the mix.)

That Cage refuses to organize this into an overall whole but rather leaves it up to the performers makes it better. In some of his scores, he used chance to write them but the scores themselves are to be strictly performed; what became more common later in his career were scores that were source materials, and the performers chose how to assemble them. (Cage always favored live performance as the way to hear music over recording.) The undetermined nature of Apartment House 1776 means that there is no definitive performance of it, and the density of it means that there is no definitive way to listen to one performance. Cage called this kind of work a “circus” or “musicircus” (dude’s brain was permanently altered by reading Finnegans Wake), where the experience would change from listener to listener and moment to moment. That Cage provides all the material and allows recorded voices also means that any musical ensemble can perform it. (If you feel, like I do, that he left out a lot of America by picking only one time and one place, then you can make your own Apartment House: apply his methods to any other time and place with its own set of songs, melodies, and rhythms. With Cage, the statement “anyone could do that” is a challenge to us, not a criticism of him.) It’s a democratic work in the best sense: available to all, impossible to reduce or summarize. It can only be experienced, and every experience is new.

The best point of comparison is cinematic: on the streets of Gangs of New York, there’s a similar artful aural chaos. Voices in different languages and accents, music and dances, sounds of the machinery of 1862 New York all mix, with no attention to who is making the sound–Martin Scorsese wisely doesn’t show all the sources. It creates the same sense as here, not of a meaning or of any kind of point, but simply a presentation of a world in all its complexity.

History, as a wise man reminded us, resists explanation. It has too many moving parts, too many voices, to summarize; every explanation or summary means a silencing. Cage often wrote that what he was doing was allowing sounds to be heard as sounds, as themselves; what he did in Apartment House 1776 was to take a step back from that. He allowed sounds to be heard with just enough context to be historical, and from that vantage he allowed history to be heard as itself: messy, contradictory, and beautiful because of that.

Cage often quoted the seventeenth-century composer Thomas Mace that the goal of music was to “season and sober the mind. . .and make us susceptible to heavenly and divine influences”; the goals were tranquility and acceptance, and many of his works do just that. What surprised me about Apartment House 1776 was how much it doesn’t do that; it was honest-to-God moving, old-fashioned, patriotic, from the first voice entering to the last, unanswered question of an unresolved harmony. (Joseph Schwanter’s New Morning for the World, an orchestral work with narration from Martin Luther King, Jr.’s texts, is right next to this.) The credo of From Many, One has been badly battered in these times, supplanted by the angry yell of Fuck You, Many from an ever-shrinking, ever-resentful One. Yet for the half hour of Apartment House 1776, the Many are there, and they’re all listening to each other. The music doesn’t argue for that America (Schwanter’s does) but demonstrates it and that’s one of the purposes of art: to make what we imagine real and tangible for the time we experience it. For all the times America has fallen short of this ideal, it’s still a good thing, “maybe the best of things, and no good thing ever dies.”