Ali expires from Netflix Streaming on September 1st. Check it out while you can.

Few genres of film are as formulaic as the biopic. The word “biopic” itself is practically anathema in some corners of cinephilia. Yet, unexpectedly, some of the most universally acclaimed films of all time are just that — biopics. Sure, people who tut-tut bios yet laud films like Raging Bull or Lawrence of Arabia will find other terms to describe those movies — “Oh, Raging Bull isn’t a biopic. It’s an spiritual drama,” or “Lawrence isn’t a biopic, it’s an existential epic.” The truth, in fact, is that such films are biopics, unequivocally, as are, if we expand the definition beyond the traditional bounds, most films — what is Taxi Driver if not a biography of a fictional man? Biopics suffer from the same disease of reputation as romantic comedies: if they’re any good, they’re not considered of their genre*

(*Annie Hall, Shaun of the Dead, Bringing Up Baby, and The 40 Year Old Virgin are all romantic comedies, and don’t forget that.)

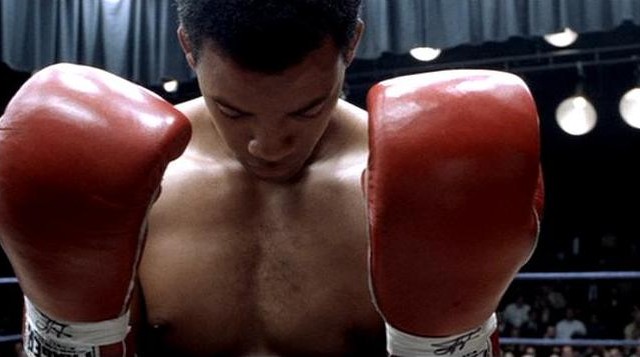

Michael Mann’s 2001 biopic Ali is something of an interesting failure, or an inconsistent but fascinating experiment. It’s good, but not as good as it wants to be, and that’s okay. Attempting to break free from, subvert, or flat-out ignore biopic cliches and formulas, Ali succeeds mightily. It doesn’t manage to keep attention for all of its expansive runtime, however, nor does everything land with the same weight, but it’s a well-thought, visually striking piece of work that attempts to take an unusual look at the life of the 20th century’s most famous athlete, the greatest himself, Muhammad Ali. Will Smith plays Ali in a film that covers the prime of the boxer’s career, from 1964, when he first whens the heavyweight title by defeating Sonny Liston in a surprise upset, to his legendary re-claiming of the title in 1974 in Zaire, Congo. That ten-year period shows the prizefighter (born under the name Cassius Clay) converting to Islam, changing his name to Ali, outliving his friend and mentor Malcolm X, going through two failed marriages, refusing to be drafted into the U.S. Army, having his heavyweight crown unfairly taken from him by the boxing commission, going all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States, and finally defeating the undefeated champ George Foreman in the greatest comeback in boxing history. Quite a lot to take in, even for a film that in its director’s cut, runs two-and-a-half hours, and not all of it resonates or takes enough time to sink in, least of all Ali’s love life. Ali meets and marries two wives over the course of the film, and his relationship falls apart with both of them, and by the end of the film, he meets his future third wife, but these relationship challenges (all of which could probably make an individual film on its own) never really connect to the rest of the film in an organic way.

But a lot does work in Ali. And the film works by avoiding cliches. Imagine the ’60s or early ’70s, as depicted on film. What do you see? Lots of bright, warm colors — sunshine-y yellows and oranges, saturated; a soundtrack of famous oldies; maybe some cliched drug trip dissolves. It’s a distancing effect, intend to prevent full engage and to instead induce nostalgia. Mann, on the other hand, uses then cutting-edge digital photography (courtesy of cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki), typically in washed-out shades of cool colors like blue, sickly green, or grey, to create a version of the ’60s that feel fresh and new, like it’s being experienced by the audience for the first time, just like how the characters in the film, and the country as a whole, had never experienced the ’60s before. In other words, it’s the 1960s, not The Sixties.

Likewise, Mann avoids filling the movie up with wall-to-wall Motown favorites or acid rock classics. Instead, the director cleverly uses new (as of 2001) covers of older songs — like Al Green’s live 1996 rendition of Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come” which underscores Ali’s reaction to Malcolm X’s murder, or a newly recorded medley of Sam Cooke covers performed by vocalist David Elliott, who plays Cooke — that are unmistakably a product of the ’60s without feeling like they’re forty years old. Just as people experiencing the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement didn’t go around saying “Wow! This feels just like a ’60s period piece,” the audience never watches Ali and thinks “seen this before.” Throughout, Ali feels entirely fresh and of-the-moment. Ali boasts an excellent, and primarily black, cast, including Jamie Foxx, stealing scenes as Ali’s colorful cornerman Bundini Brown, Giancarlo Esposito as old-fashioned Cassius Clay Sr., Barry Shabaka Henley as National of Islam money man Herbert Muhammad, and a small, but well-acted performance by former heavyweight boxer Michael Bentt as the notorious Sonny Liston, but the film of course rests on the shoulders of Will Smith as Muhammad Ali. And he’s. . . good. But not perfect.

Smith’s performance as Ali is a tricky one, as the film both wants to show you an Ali you never understood (the film was promoted with the slogan “Forget What You Think You Know”), but still wants to keep him somewhat distant. When he’s playing the Ali who became famous, the guy who appeared in press conferences, in the ring, on talk shows, he feels hollow, somewhat “off.” Like he’s reading lines. This is very much intentional. The film is, if nothing else, made to show the audience how “Ali,” as we know him, was a construct of the real man Muhammad Ali — that the “float like a butterfly sting like a bee” raps and the trash talk and the political grandstanding, it wasn’t “fake,” Ali still meant what he said, but that it was still very much an act, a performance. The real Ali, Mann and company are suggesting, created the larger-than-life Ali, the Black Superman, to take on his enemies, both inside the ring and outside the ring, while attempting to appear fearless. In a way, Ali is something like Batman Begins or a Zorro movie, showing how a determined man can craft a superhero persona that can stand for more and be bigger than any real man. At key moments in the film, we see Smith, as the Real Ali, have to take a moment to “get into character” in order to be the Famous Ali. The film never tells us this with dialogue, but instead wants us to figure it out for ourselves, though that may have had something to do with the film’s initial popular failure. It’s subtle, much more subtle than your typical studio film, even the supposed prestige fare. Somewhat unfortunately, Smith is not quite up to the demands of the role. The hollowness of his boasts and his trash talk are intentional, but in the hands of a better actor, let’s say a younger Denzel Washington, they could have balanced both the staginess and the charm of Ali at the same time, whereas Smith comes off somewhat deflated. In scenes where Ali is meant to do what Michael Mann heroes spend half their time doing, sitting alone, quietly thinking, contemplating the future, Smith doesn’t quite connect with the material in the way that Robert De Niro did in Heat, or Russell Crowe in The Insider did, though he doesn’t embarrass himself. It’s still a credible performance, and contributes to perhaps the film’s best scene: Ali, fresh off of winning the heavyweight title, flirts and dances with a girl named Sonji (Will Smith’s real life wife Jada Pinkett Smith) in a nightclub. It’s a fantastic sequence, romantic and sexual, carnal and emotional, all at once, as Mann shows their early slow dancing gradually fade into passionate lovemaking, all to the belting, beautiful performance of Shari Watson’s “For Your Precious Love.” It’s a scene that is almost too good — the Smiths have insane chemistry, even surpassing one’s expectations, even though Ali’s marriage to Sonji flames out after less than a year — but one that is so deeply sensual that it almost envelops the audience, sinking them into a deep blue sea of seduction and intimate physicality.

For moments like the nightclub scene, for Jamie Foxx’s Bundini confessing that he sold Ali’s championship belt to buy heroin, and for the simply jaw-dropping impressionistic montage of Ali’s upbringing that opens the film — one could practically teach an entirely film course based entirely on those ten minutes — for all those moments, and for a general feel, a deepness, a willingness to take time and to let a moment sit and breathe and die of its own momentum, Ali is enough to recommend, and enough to go back to, as I have, time and time again. And just as Mann intended, it always feels new.