Yes, this is entry number 3 and, technically, this is yet another Not A Remake. This is technically a sequel to a prequel reboot with a plot that closely resembles a remake and will eventually tie the reboot prequel to the original in the series. Which makes it something like a represequel or maybe a reseprequel. Whatever it is, the plot is close enough for this very loosely defined series, and I’m probably being overly defensive about this. But, dammit, this needs to be talked about.

The original Alien was a standalone science fiction/horror movie where a predatory new species kills off a deep space mining crew one by one. Dan O’Bannon (Total Recall, Lifeforce) launched the Nature Gone Amok genre into space, granting him an all new predator designed for maximal fright; an old formula turned into a revelation through one marked change. O’Bannon didn’t stop there; he filled Alien with an anti-corporate message so bleak and open-ended that it spawned another five films (with at least one more on the way) where the villain isn’t just the alien species but also the corporation that may have created it.

At the beginning of Alien, the crew of the Nostromo mining freighter is in a deep sleep stasis while the ship travels back home to Earth. The Nostromo itself feels like the inside of an old gas station garage: pin ups are in the galley, magazines are readily available, the ship’s innards are dirty and grungy with steam pouring into the hallways. It feels like the Starship Enterprise mated with an old tow truck. To match, the crew has a down rent feel to their looks and personalities.

Tom Skerrit’s Captain Dallas looks and feels more like a rust belt father than the steely Commander Viper of Top Gun. Yaphet Kotto (Blue Collar) and Harry Dean Stanton (Repo Man) are the grumpy scraggly maintenance men worried about getting their fair share of the money. John Hurt, the first human we see, is a skinny freckled man with bags under his eyes and a perpetual rats nest of hair. Even the two women, Veronica Cartwright and Sigourney Weaver, feel like two gas station managers who have had to toughen their skin to deal with all the bullshit from the men of the world. Only young, short, and pleasantly rounded Ian Holm is out of place as the Nostromo’s last minute replacement of a science officer.

These are hard working industrial people trying to make a paycheck-to-paycheck living to support themselves and their families. When the ship wakes them up, they expect to be close to home, ready to relish in their earnings until their next job. In reality, the ship has “picked up” a “stray” maybe-distress signal from a random planet and adjusted course to investigate the source and help out “anybody who might be there.” I put all of these phrases in scare quotes because the real story is that the signal is actually a warning telling people to stay away. The signal is also where their company, Weyland-Yutani Corporation, has identified (if not engineered) the titular predator, a xenomorph, for use as a killer war machine. Weyland-Yutani doesn’t just mine for minerals in deep space, they’re ostensibly a ship manufacturer, an android manufacturer, and the maker of military weapons.

When Alien came out in 1979, the general mood of America was starting to be wary of the rise of corporate dominance mixed with the globalist view of politicians and the closing of factories and mines in the rust belt. 1977’s Slap Shot was all about the closing of a local mill for increased profits, and the relationship between the amateur hockey team with the mill-working audience. 1978’s Blue Collar was an intensely horrific noir about a car manufacturer whose corporate machinations destroyed worker relationships and kept wages suppressed. Number one films at the box office in these three years included the grungy working-class Saturday Night Fever, the working class anti-war movie Apocalypse Now, and the underdog uprising of Rocky.

The angsty distrust of corporate America seethed through Alien. The worst aspects of corporate America are shown through through Ash, Ian Holm’s inhuman science officer. Even as the ship is landing on the desolate planet, Ash is already anxious for the crew to meet the alien while preventing Ripley (Weaver) from stopping the chain of events. After she decodes the signal as a warning and wants to stop the crew, he reminds her that they’ve already been gone awhile and by the time she gets out there, they’ll have discovered the true source of the beacon as well. Ash is the one that goes above Ripley’s authority to let the alien on board while it’s attached to John Hurt’s face, ignoring quarantine protocol. Ash is the one who has special permissions above and beyond even the captain of the mission. He’s the one who knows that Weyland-Yutani wants the alien at all costs; only somebody as callous as a corporate robot would think its ok for the human crew to be expendable.

All of this anti-corporate sentiment is mere window dressing for a perfect slow burn horror movie that begins as a working class drama and incrementally builds into an edge-of-your-seat terror with sirens blaring, warning lights flashing, an ominous voice counting down the seconds, and a sweaty final girl going head to head with Weyland-Yutani’s “perfect” war machine.

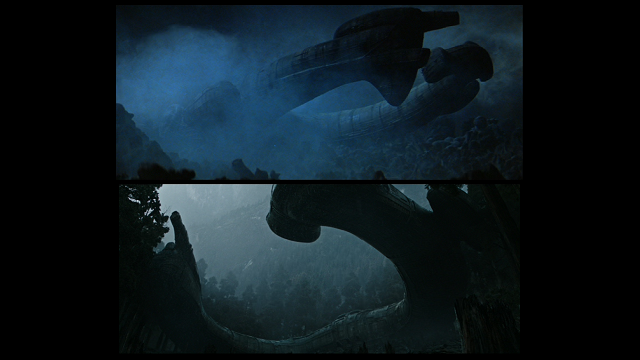

Barring a senseless prologue, the prequel Alien: Covenant begins with a near identical first act. The Covenant, a Weyland-Yutani ship, is sailing through the cosmos with a sleeping crew when a space anomaly hits the ship, waking the crew mid-flight. The shock to the system kills the captain (James Franco) in stasis, leaving first mate Chris Oram (Billy Crudup) in charge as a last minute replacement similar to Ash. While repairing the ship, the Covenant catches a signal amidst the anomaly that includes a snippet of John Denver’s Take Me Home, Country Roads. Finding the source to be on an inhabitable planet, new Captain Oram investigates (against the wishes of the crew). Much like the ill-fated members of the Nostromo, the Covenant crew hike their way to the source of the signal, finding an identical ship to the original one in Alien where crew members are impregnated by hyper-intelligent sports who soon spawn aliens that burst from their bodies. And that’s where the similarities end…

The differences between Alien and Alien: Covenant at first seem cosmetic. When the Nostromo is asleep and on auto-pilot, the whole crew is in stasis…including Ash the android; when the Covenant is asleep and seeming on auto-pilot, its android, Walter, is walking around monitoring the ship, manually recharging its batteries, and monitoring the sleeping crew members and passengers. Mother has shirked her no nonsense sensibilities to idly chit-chat with Walter (“Seven Bells and All’s Well”). Where the Nostromo was dirty, grungy and looking like a gas station garage, the Covenant is a clean, pristine gorgeous piece of comfort machinery. This is less the towing vehicle of Alien and closer to the beauty found in Passengers.

Despite having Danny McBride as Tennessee the cowboy-hat-wearing hotshot pilot who can recognize John Denver, the Covenant’s crew is more polished and clean cut than the working class Nostromo’s mining crew. Most of the Covenant’s pilgrims feel like college-educated first adopters who think it would be neat to build a cabin on a different planet and live off the roughage although they wouldn’t be able to do any actual farming without a manual. Even Crudup’s Oram, a man of faith, strains to be seen as an insecure working class leader in a junky t-shirt, although his characterization as a compassionate but inhumane rebellious Christian never feels like a complete character anyways. We’re expected to believe that the the Jesus Freak who expected his crew to not honor the dead is the same person who decides to go off mission and land on a foreign planet because he cares about his crew’s comfort?

The differences between the movies continue extend to the unnamed planet. When the Nostromo ‘s lander arrives on LV-426, the planet is aggressively hostile and breaches the lander’s hull with a misplaced giant boulder. A cold dark storm rampages all around the craggy dark and grey atmosphere, all adding up to “humans aren’t welcome here.” It’s far different on the unknown planet of Alien: Covenant. Although there’s a raging storm/hurricane, the planet is saturated with color. The planet is plentiful with Earth-like natural beauty: waterfalls, forests and jungles, foliage. This is a paradise compared to LV-426, with one excetion: the aliens.

The first set of aliens on the new planet are not the full-fledged version of the Xenomorphs we’ve come to know and love since the very first Alien. The Xenomorphs have a very distinct life cycle of Queen -> Egg -> Facehugger -> Implanted Embryo -> Xenomorph or Queen. Since Alien, many have considered the facehugger, with its long ovipositor thrust down a throat, to be a metaphor for male rape. The new aliens are Neomorphs, and they most pointedly are not rapist facehuggers. The Neomorphs, instead, infect through magical spores that arise from broken eggs and plant themselves into somebody’s skin without them knowing. Yes, the new aliens infect by earworm spores, so tiny that they can penetrate pores yet can grow into a baby alien in a matter of hours.

Despite all initial appearances with a run time 10 minutes longer than the original, Alien Covenant is no slow burn horror film. In the original Alien, the first chest bursting happens over an hour into the film. In the Covenant, two separate aliens have already burst through the bodies, and the crew have already destroyed their lander through a zany set piece of officers slipping and falling on blood and accidentally shooting ammo at explosives on the ship. Alien Covenant isn’t here to scare. It’s here to philosophize, and that’s where Alien Covenant takes a turn.

With this prequel trilogy, Ridley Scott has taken back the Alien universe and begun asking about our origins and what it means to be human. In Prometheus, Peter Weyland was searching for the answers from humanity’s forefathers, “the Engineers.” The humans are seeking their creators and their creators are seeking to destroy their creations. This is contrasted through David, Weyland’s then-latest android. As the humans were created in the engineers’ image, David was created in humanity’s image. David lives among his creators, and regards them more as a nuisance. By Alien Covenant, David is so bitter as his creators, he destroys the engineers for creating the humans and prevent the humans from spreading throughout the galaxy. In turn, he creates the Xenomorph from the Neomorph for maximal murder.

This is a very drastic change from the morality of Alien. In Alien, the company Weyland-Yutani was destroying humanity for its own profit. Like so many Xenomorphs, that anti-corporate messaging has been jettisoned in favor of a rogue mad scientist plot. David isn’t under the employ of Weyland-Yutani. He’s a renegade. Through the creation of a new species to kill humanity, David is creating his own religion where he is his own God. In Prometheus, David is directly responsible for waking an engineer up to murder Peter Weyland. In Covenant, he’s acting out of his own idle viciousness rather than gearing up for financial gain. The killings in Covenant are pointedly NOT because of the corporation, but because of the independent off-mission decisions of two religious fuckwads: Oram and David (who first appears dressed like a monk who needs a haircut).

Prometheus and Covenant aren’t the first times religion and fate have played a role in the Alien series. In Alien 3, Catholicism and Fate interweave throughout the film to give Ripley her final sacrifice. There, a whole prison of extreme offenders are forced to believe in religion as their source of solace, Ripley is fated to be intertwined with the Xenomorph. And, yet, Alien 3 never forgets that Weyland-Yutani is behind it all. In the end, Ripley has to make a decision of life where the company wins, or death where the company loses; Weyland-Yutani was always the series’ big bad enemy. In this prologue series, in the new-fangled era of pro-corporate pro-government propaganda, Weyland-Yutani is almost an innocent bystander to all that will befall Ripley in the main series. In Covenant Their only guilt is by association.

There was a moment in Alien Covenant where one could truly feel the differences between it and Alien. Sometime around the hour mark, just about the time that the alien would be bursting out of John Hurt, David and Walter have a heart to heart where David teaches Walter how to play the recorder. David, who does wear a skin tight but non-explicit onesie throughout the film, tells Walter “You know how to whistle, don’t ya, Walter? You just put your lips together and blow.” Well, not actually. He tells Walter to puts his mouth against the embouchure and blow. That’s when he teaches Walter how to finger his long flesh-colored pipe. It’s not quite oral sex 101, but it does culminate in Michael Fassbender making out with himself.

At this point, any self-respecting horror fan would be shouting “We don’t have time for this!” One would think most self-respecting science-fiction fans would be shouting “what’s the point?!” The only justification I can come up with is that Ridley Scott wanted to make a grand guignol version of Alien and ended up doubling down on the camp. In actuality, in my second viewing of this movie, this was the point I texted my friend saying “two Michael Fassbenders are teaching each other how to finger their flute. What the hell is this movie?”

The last bit of philosophizing, and the last vestige of originality, in Alien Covenant is David’s story that they’re actually on The Engineers’ home planet. David killed the engineers by releasing the biochemical black goo from Prometheus as a virus onto the Engineers’ city, killing their whole species. He believed that the Engineers could not live to recreate the humans. They had to die, as do the rest of the humans on the Covenant.

After a long stupid finale where two crew members get rid of the final xenomorph through the use of cranes and by releasing a couple of construction trucks (vaguely reminiscent of Aliens), Scott flips the ending on us. Alien ended in a moment of earned peace. Ripley, the final girl, has vanquished the alien and can slumber with her kitty as her ship sails on to safety. Alien Covenant twists the ending by revealing David to have killed Walter in an off-screen battle, and is now taking his place set to kill the surviving crew. David also rescued an alien embryo and saves it among the human babies. This is Ridley Scott informing us there is at least one more movie to come, unlike Alien which was a perfect standalone.

Perhaps that is the biggest difference between Alien and Alien Covenant, which is also a great difference between movies from the 1970s and movies from today. Alien built a relatively complete world with open ended possibilities, but told a complete story within those confines. The audience assumed that Ellen Ripley survived and lived happily ever after. It had a beginning, justifications, and an ending.

Alien Covenant is more interested in the world building of modern serialized cinema. In 1980, the year after Alien hit theaters, George Lucas released a sequel to Star Wars. The original Star Wars was written so it could survive as a stand-alone film. Its sequel, The Empire Strikes Back, was not. Empireis a middle entry that offers no conclusions, content with furthering the story and ending on a series of cliffhangers. That type of serialized storytelling has returned with a vengeance, now afflicting Alien Covenant. There are no conclusions in Alien Covenant, it’s goals are to build worlds and get us from Movie A to Movie C with a major cliffhanger advertising the next movie. Instead of telling a complete story, Alien Covenant is perfectly content to coast on its own bullshit mythology and philosophizing. Perhaps that scene of David and Walter playing each others flutes was an astute metaphor after all.

There is one scene that has people bugging out. At the very beginning of Alien Covenant, long before everything happens, Walter is tending to a bunch of embryos. He sees one, and discards it in a biowaste container. We assume that the embryo is dead, but could he be covering up for Weyland-Yutani? Is this going to be revealed in the next movie? Or is this just convenient for David to put the alien embryo in its place? Let me refer you back to that flute scene.