ed’s note: Contained within are notes detailing the societal placement of two films in the S&M erotica genre: Fifty Shades of Grey and The Duke of Burgundy. This article should not be seen as a legitimizing of either film, in so much as they are both legitimate elements for discussion. Trigger warnings for BDSM and discussions of rape.

Sexuality comes in a wide variety of shapes and forms. From heteronormativity to the spectrum of sexuality under the queer umbrella, the biggest movement we had at the end of the 20th century was the realization that we are not alone in whatever our sexual desires are. We are not complete deviants. Whatever our sexuality may be, there is probably somebody who shares a similar sexuality, or at least presents the needed counterpart to our sexuality.

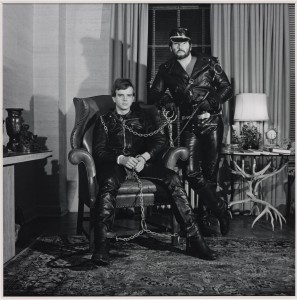

Even though the realization that other people react like us has been fostered by modern updates in communication, depicting non-normative sexual acts as an art form dates back to ancient times. From Greek mythology through the Marquis de Sade into the photography of Mapplethorpe, artistic representations of aberrant acts have connected people through their carnality as much as they repulsed the mainstream.

Even though the realization that other people react like us has been fostered by modern updates in communication, depicting non-normative sexual acts as an art form dates back to ancient times. From Greek mythology through the Marquis de Sade into the photography of Mapplethorpe, artistic representations of aberrant acts have connected people through their carnality as much as they repulsed the mainstream.

The form of what turns people on is of as wide variety as the content itself. Some are turned on by romance, some by carnality; some are turned on by domination, some by submission; some by rigidly adhering to the status quo, some by acts explicitly upturning what is to be expected of them. To say that what turns one person on is wrong simply for the content contained within is to misunderstand the role that erotica plays in our sex life. In the world of transgressive erotica, the lines of what turns a person on become blurred when they clash with the way our world functions.

The role of pornography in society, and the feminist response to it, is dictated by an individual’s perception of sexual art. Anti-pornography feminist Andrea Dworkin has derided pornography as an extension of the patriarchy, frequently used to demonstrate a man’s power over women. Pro-sex feminist Ellen Willis responded by saying that Dworkin’s claim that pornography demonstrates acts of violence upon women is rooted in the antiquated beliefs that men are sexual beings and women merely suffer sex for procreation and the man’s pleasure. Both of these views of pornography examine the varieties of homosexual female couplings and, appropriately, ignore the variety of couplings for homosexual males.

Dworkin’s anti-pornography reaction can be traced back through the patriarchy to who creates pornography. The majority of pornography through history has been written by men. Men had the privilege of creating pornography because men had the privilege of creation. Because men were the content creators, men self-defined their role as sexual beings. Through the control of creation, men had the agency to control our sexual fantasies. Admittedly, these are largely broad and blanket statements about fiction. There are exceptions to the male creator rule, especially some strains of lesbian literature, but the majority of pornographic product has been by men, for men.

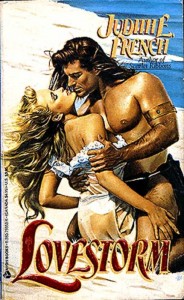

Erotica for women in North America has traditionally been reserved for the stroking of the heart more than the stroking of the clitoris. Harlequin Publishing held a domination in female romance for ages, publishing chaste depictions of women being swept off their feet by charming and handsome men of their fantasies. Usually referred to as bodice-rippers, many of these novels reinforced the male-dominant, female-submissive dichotomy allowing the heroines to coyly manipulate the heroes into taking control of the relationship. While modern times have seen the creation of pornography for women by women, romantic softcore erotica remains the main outlet for women. Meanwhile, erotica for men has increasingly turned into graphic pornography with more attention to the acts than the characters participating in the act. If erotica and pornography gendered for women are typically about stroking the heart and mind, then erotica and pornography gendered for men are typically about visual pleasure, the male gaze, and stroking the genitals. Where they remain the same is the intention for the audience to mentally place themselves in either the shoes of one or more characters, or the shoes of the creator.

Erotica for women in North America has traditionally been reserved for the stroking of the heart more than the stroking of the clitoris. Harlequin Publishing held a domination in female romance for ages, publishing chaste depictions of women being swept off their feet by charming and handsome men of their fantasies. Usually referred to as bodice-rippers, many of these novels reinforced the male-dominant, female-submissive dichotomy allowing the heroines to coyly manipulate the heroes into taking control of the relationship. While modern times have seen the creation of pornography for women by women, romantic softcore erotica remains the main outlet for women. Meanwhile, erotica for men has increasingly turned into graphic pornography with more attention to the acts than the characters participating in the act. If erotica and pornography gendered for women are typically about stroking the heart and mind, then erotica and pornography gendered for men are typically about visual pleasure, the male gaze, and stroking the genitals. Where they remain the same is the intention for the audience to mentally place themselves in either the shoes of one or more characters, or the shoes of the creator.

The theory behind the second-wave anti-pornography has roots in trends and theory. A constant stream of male-dominant imagery reinforces women’s roles as submissives, and a constant stream of women fetishized as objects reinforces female objectification. By constantly reinforcing these two poles, women are conditioned to be passive in their desires and everyday behavior. This theory leaves little to no room for female desire and choice. The theory doesn’t allow for the people who actively choose to be submissives and objectified. Conventional wisdom, by way of rumor, states that many dominant men prefer being passive or submissive lovers. However, the mere presence of dominatrices with submissive male clients indicates that widespread presence of dominant cultural trends do not dictate social behavior alone.

This theory of culture dictating behavior extends beyond romance and sex into the realm of aggression and violence. When a teenager commits an act of extreme violence, frequently the news media trots out violent media, such as video games and aggressive music, to point to logistical reasons for why Teenager A committed horrific act B. The most well known case of this is the Robin Hood Hills murders, where three innocent teenagers who listened to heavy metal were railroaded as criminals for their music choice. This same rationale was trotted out as reason for the Columbine shooting in 1999, where Marilyn Manson was conveniently trotted out as an influence.

The question of whether art can influence people’s behaviors has long been a debate. The Marquis de Sade, a corrupt man of sexual ill will – according to several accounts, he had sexual improprieties with his employees, as well as a 14 year old girl – was imprisoned and then committed to an asylum for his works of erotic fantasy, Justine and Juliette. The Hays Code was founded in enforced morality. Many acts of censorship are committed because the works of art would cause one to act out “immoral” behaviors, with “immoral” being loosely defined with terms appropriate to the era and the ruler or enforcer of said censorship.

In truth, many teenagers experience pornography before they actually experience the physical act of sex. Outside of child molestation, many sexually active people have learned about the physical act from their surrounding world well before they have actually attempted these physical acts. If both textual and visual pornography can be instructive on the physical acts, then could it be argued that pornography is also instructive on social behaviors? Similarly, does fiction reflect or dictate social behavior in the viewing audience?

Such are the arguments at the center of the controversy surrounding the book, and now film, Fifty Shades of Grey. Developed as internet slash fiction using Twilight characters, E.L. James’ novel straddles the line between Harlequin romance and hardcore pornography. Though poorly written, the purple prose of Fifty Shades appeals to the irrational erogenous mind while couching the sexuality in trashy Harlequin tropes. When translated to a film, the Harlequin tropes emerge as the dominant storyline while the pornographic scenes are tamed for a wider audience (and an R-rating).

Such are the arguments at the center of the controversy surrounding the book, and now film, Fifty Shades of Grey. Developed as internet slash fiction using Twilight characters, E.L. James’ novel straddles the line between Harlequin romance and hardcore pornography. Though poorly written, the purple prose of Fifty Shades appeals to the irrational erogenous mind while couching the sexuality in trashy Harlequin tropes. When translated to a film, the Harlequin tropes emerge as the dominant storyline while the pornographic scenes are tamed for a wider audience (and an R-rating).

The throwaway plot of the first film in the series concerns a virginal woman, Anastasia Steele, meeting a troubled rich man, Christian Gray, who distances himself from everybody. His romantic interactions with women are filtered through the lens of BDSM fetish, where he is a dominant male possessing a submissive female. As he courts Anastasia, he slowly starts dominating her life by monitoring her behavior and engaging her in kinkier and kinkier play. But, she’s also playing a bossy bottom, where she is controlling his behavior through subtle manipulations of her own, frequently changing his traditional behavioral pattern.

The explicit sex scenes of the novel, and the moderately frequent, if not explicit, sex scenes of the movie have created a controversy over whether Fifty Shades is a harmful piece of pornography that bastardizes modern BDSM role play while proving to be an instructive text for beginning participants, or whether it is a relatively benign example of extremely explicit Harlequin romance allowing women to explore their submissive fantasies through a safer environment. It also asks the question, can pornography perpetrate transgressive fantasies and still remain harmless?

At the heart of that secondary question is the ownership of fantasy. E.L. James is a female author exploring her own transgressive fantasies of being obsessively and dangerously wanted and desired through fan fiction. The erotic exploration proved to be universal enough to become a worldwide phenomenon. In a similarly transgressive fashion, progressive females and rape victims alike have used fictional rape fantasies to explore their own irrational erotic desires without compromising their personal moral code. In essence, it is alright for Anastasia Steele to be in the middle of an abusive relationship because she’s not a real person and merely an avatar for the female creator and the female reader? Or, will these transgressive fantasies, when released into the public, perpetrate their immoral behaviors through unintended real life behavior changes? Are rape fictions allowed by the moral dictators, so long as women are exploring their fantasies through them? Are rape fictions verboten as soon as we can prove one actual rape happened because of somebody took the fantasy too far? Such is the moral conundrum presented by ownership of fantasy.

The critics of Fifty Shades have pointed to statistics of women in abusive relationships, and the victims’ stories that parallel the same beats of E.L. James’ novel. Though these beats have been toned down in the film, some of the scenes in the adaptation have been considered “rape adjacent.” In addition, many of Christian’s behaviors are violating, objectifying, and just plain creepy. The criticism that Fifty Shades is an instructive text for spousal abuse and rapists have roots in the second-wave criticism of pornography being socially instructive.

These questions are not aided by Sam Taylor-Johnson’s cinematic blandness. The film of Fifty Shades creates a very polished version of reality. All of the distancing effects that happen when we’re reading a fictional story disappear when the visual style is rendered mundane. While not representing a documentary by any means, the visual style of Fifty Shades is closer to Garry Marshall’s semi-realist romance Pretty Woman (which shares many plot elements with Fifty Shades) than to the hyper-stylized Russ Meyer.

These questions are not aided by Sam Taylor-Johnson’s cinematic blandness. The film of Fifty Shades creates a very polished version of reality. All of the distancing effects that happen when we’re reading a fictional story disappear when the visual style is rendered mundane. While not representing a documentary by any means, the visual style of Fifty Shades is closer to Garry Marshall’s semi-realist romance Pretty Woman (which shares many plot elements with Fifty Shades) than to the hyper-stylized Russ Meyer.

If Fifty Shades of Gray is a mundane pornographic text which confuses instructive pornography and Harlequin romance, The Duke of Burgundy presents the diametric opposite. The Duke of Burgundy presents a lesbian relationship founded in fantasy Dominant/submissive role play, but grounds it in the everyday mundanities of such kinky role play. Evelyn is in a relationship with Cynthia dependent on submissive role play. Evelyn likes being forced to clean boots, be tied up, placed in a box, or even used as a cushion. But, she controls the scenes they play. She buys fetishized clothing for Cynthia to wear during their scenes, writes the scripts for Cynthia to use, and researches the play furniture they can buy.

Where Anastasia tries to control the relationship through manipulation and game playing, Evelyn controls the relationship through direct requests and demands. Christian controls his scenes with Anastasia (though she has a safe word), but Cynthia has little control over her scenes with Evelyn, frequently expressing distress at having to play the scenes. Cynthia and Evelyn’s role play is always presented as role play, while Christian and Anastasia’s fetishistic sex is presented as a singular force with their relationship. It is in these differences that The Duke of Burgundy can be considered an instructive text in safe, sane, and consensual fetish role play compared to Fifty Shades‘ Harlequin romanticization of kink.

The differences in intent is simultaneously emphasized and confused by the cinematic techniques of The Duke of Burgundy. Written and directed by Peter Strickland, noticeably a male, the visual style of Burgundy recalls the visual motifs of 1970s eurotrash fantasias created by Jean Rollin and Jess Franco. Seemingly filmed in a classic European chateau with an expansive garden in the middle of a village, Burgundy visually emphasizes the fantasy of the lifestyle through an old world setting, a digital replication of film grain from a bygone era, and editing techniques that occasionally leap into the surreal. Though Strickland is making a more instructive text, he couches it in a fantasia visual motif. This contrasts to Taylor-Johnson’s fantasy text couched in a polished but mundane visual motif that emphasizes the reality over the fantasy.

The differences in intent is simultaneously emphasized and confused by the cinematic techniques of The Duke of Burgundy. Written and directed by Peter Strickland, noticeably a male, the visual style of Burgundy recalls the visual motifs of 1970s eurotrash fantasias created by Jean Rollin and Jess Franco. Seemingly filmed in a classic European chateau with an expansive garden in the middle of a village, Burgundy visually emphasizes the fantasy of the lifestyle through an old world setting, a digital replication of film grain from a bygone era, and editing techniques that occasionally leap into the surreal. Though Strickland is making a more instructive text, he couches it in a fantasia visual motif. This contrasts to Taylor-Johnson’s fantasy text couched in a polished but mundane visual motif that emphasizes the reality over the fantasy.

Last week, this essay became far more problematic when news reports of a university rape were released last week. The rapist used the defense that he was recreating scenes he saw in Fifty Shades of Grey that same night, ignoring his victim’s cries of “No” as he tied her up, beat her and raped her. His use of Fifty Shades as a defense bolsters the critics’ views that Fifty Shades is a pornographic instructive text and not a Harlequin romance intended for transgressive fantasy. As per our social scripts, the critics of those critics say that the rapist was just using Fifty Shades as an excuse and had the behavior in him already.

At the end of an essay of sufficient length, a conclusion is expected. I cannot provide one. I am a proponent of transgressive erotica, and believe that women have a right to explore their sexual desires in a manner they see fit. However, I think the arguments that Fifty Shades of Grey is a problematic text are compelling. Especially in cinematic form, Fifty Shades may be consumed by those who will confuse the fantasy portion with reality, and sometimes proliferation of a regressive attitude does lead to changes in behavior. Instead of supporting or condemning Fifty Shades of Grey, I implore people to watch The Duke of Burgundy because I think it’s a better film.