Steven Soderbergh is always on the hunt for ways to make movies and TV shows faster and more efficiently, and now, he’s discovered that the ultimate solution to that has been in his pocket the whole time. He has used his iPhone to shoot two films now, and the first of those films, Unsane, is finally upon us (I would not be surprised if the second, High Flying Bird, also comes out this year). Soderbergh’s first foray into outright horror (although he has said, not wrongly, that Contagion is a horror movie), it follows Side Effects‘ path as being simultaneously a trashy b-picture and a high-minded social commentary, not to mention a showcase for Soderbergh’s new toy. But does it succeed at any of those goals? The answer will surprise you only if you’ve read literally nothing else I’ve written about Soderbergh before.

Sawyer Valentini (Claire Foy) is what some people would call “high-strung”. She has good reason to be. She had to move from Boston to Pennsylvania to get away from David Strine (Joshua Leonard), who has been stalking her ever since she took care of his dying father. She still has PTSD from her experience with him and keeps seeing him around, and decides to talk to a therapist about her problem. One bit of glanced-over paperwork later, she ends up signing herself up to be committed at the Highland Creek mental institution, first for 24 hours and then for a week after her protests get violent. But that’s the least of her troubles, because who seems to be an orderly in the hospital but David, under a different name. Or is she losing her mind?

(There are SPOILERS in the next two paragraphs; I don’t give away any of the third act, or really much beyond the film’s first half, but if you want to go in completely cold, don’t read these.)

The question of “are they losing their mind” has sustained the entire running times of many horror films, but it is answered pretty quickly into Unsane‘s running time. Soderbergh wrings some initial tension out of the bizarreness of her situation and the potential for it all being in her head, but no, she is not losing her mind, yes, the stalker is really there, and yes, the hospital really is taking advantage of her. From there, the movie shifts gears into horror of a more literal kind, but Soderbergh still finds a way to play with the audience’s feelings towards Sawyer even after it becomes clear we can believe her. She doesn’t behave in quite the “right” ways to her situation, taking aggression out on a particularly unstable fellow patient (an unrecognizable Juno Temple) and continually getting dragged back and tied to her bed by the staff. She’s not the most likable person in the world, and the world around her takes that as ample reason to torment her (it reminds me a bit of Elle, which similarly dared the viewer to be turned off by its traumatized protagonist). This movie was shot months before the Weinstein story and the beginnings of Time’s Up, but it feels completely of the moment, dealing with our hesitancy to believe women when they don’t act a particular way. And David is a particularly skin-crawling depiction of the worst of men, believing that he’s entitled to Sawyer despite all her protestations. The real horror is not that you can’t trust your mind, it’s that nobody else cares about trusting it.

David is also an example of an increasing favorite antagonist of Soderbergh’s; the individual taking advantage of the sins of capitalism. Almost all of his work from Che on sees Soderbergh painting unflattering pictures of corporations and the agents of capitalism, and Unsane has a doozy of one. Highland Creek is an insurance scam masquerading as a hospital, hiding permission for commitment in benign-seeming paperwork and holding these perfectly healthy patients until their insurance stops paying out. This is, horribly enough, a very real phenomenon, and also a neat stand-in for the increasing nightmare of the American health-care system. But Soderbergh seems maybe more disturbed by the actions of David, who knows about the evils of Highland Creek, and not only does nothing to stop them, but actively uses them to get across his own nefarious agenda. Like Mark Whitacre, Rooney Mara in Side Effects, and Jude Law in Contagion before him, David sees the failings of the system as an easy in-road to get what he wants, but he tops all of them in the sheer awfulness of his goal. I’ve seen many complaints about the film’s turn from the insurance angle to David, but it really works for me, equating physical violation and the violation of your rights by suits somewhere far away.

(There are no more SPOILERS after this point.)

In one scene, the other patients at Highland Creek have a meeting while playing on the TV behind them is a clip from Full Frontal, Soderbergh’s first experimentation with digital video (that anyone in the facility would want to watch that particular movie makes no sense at all, but reader, I lost my goddamn mind when I noticed this). Full Frontal‘s low-res, murky imagery was the source of much derision when it was released, but watching it now, one can see why Soderbergh gravitated towards it, with the freedom it allowed him for camera positions (like getting to go behind a hotel-room vent and film a sex scene through the slats) and the interesting way it takes in light (like another hotel-room scene, where the light completely changes depending on how the drapes are moving). And watching Unsane, one really understands why Soderbergh opted for the iPhone here. Through the super-sharp, unmistakably digital imagery of the iPhone, one immediately gets the sense that Sawyer is living a life that has gone completely out-of-whack (she’s even boxed in by the aspect ratio, which is barely worthy of being called widescreen). Close-ups on Sawyer or any of the other characters have entirely too much visual information (you will become intimately familiar with Claire Foy’s pores watching this), and are made all the more uncanny by having the actors stare dead into the camera/phone. And Soderbergh can film in odd new places, including in the bushes, peering at Sawyer from a distance, or from the point-of-view of a sink as Sawyer uses it following a botched hook-up. And that’s just before she’s committed, at which point Soderbergh starts going crazy with De Palma-esque tracking shots through the facility’s hallways. But the craziest thing is that you start getting used to the iPhone look in the facility, with its nauseating fluorescent lighting and lifeless walls starting to look normal. Whenever Soderbergh leaves the building (or enters a solitary-confinement room, or does a disorienting double-layer of body-cam shots), the effect wears off, and you’re left to confront the fact that you’ve started to get comfortable with is completely fucked up. It’s an at-times aggressively ugly movie (and sometimes an inexplicably beautiful one), but the look is never not perfectly suited to this material. I don’t know how Soderbergh’ll change up the iPhone look for something that isn’t supposed to look unnerving (High Flying Bird was shot anamorphic on his iPhone, so maybe that will help to soften the image a little), but this is a wonderful test-run for what might be a serious new format.

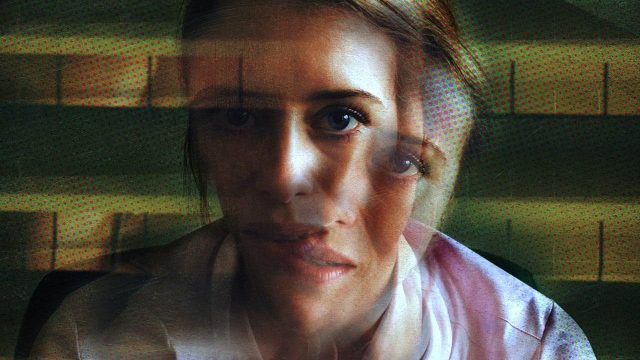

Now, let’s talk about Claire Foy. The other performers in the film do well, with special commendation to Joshua Leonard’s appalling, terrifying neediness as David, Temple’s feral energy as Sawyer’s antagonist at Highland, and Jay Pharoah’s charm and comic relief as a Highland patient who knows everything about the place and strikes up a friendship with Sawyer. But this is ultimately the Claire Foy Show and everybody else is a background player. I have not watched The Crown or anything else she’s been in, so her performance here effectively came out of nowhere for me. She’s absolutely terrific as a woman being gradually broken down, She puts on an almost Judy Davis-esque American accent that suggests “I’m in charge here”, at least up to the point when she can no longer even pretend to have things in control. Her multiple almost-direct-to-camera close-ups only highlight the intricacies of her performance, seeing her trying to deduce her way out of her situation while barely containing either righteous anger or deep sorrow (both in Highland and out; just look at her reaction to her boss clumsily making a pass at her early on). And when she fully lets loose, as in two climactic duets between her and David, her force is earth-shaking. Foy runs the gamut from dangerously fragile to capable of eating you alive, and she’s absolutely convincing in every mode. I guess enough people watch The Crown that she’s already a star, but for me, this is a total movie-star-is-born performance, and I now look forward to seeing her take on Lisbeth Salander. Hey, wait a minute, is Soderbergh now only working with actresses who’ve played that character?

As a technical showcase, a nasty bit of psychological horror, a star vehicle, and a high-minded expose of criminality at both the highest and lowest levels of society, Unsane is a success. It’s never empty calories, but it still delivers the thrills, chills, and even spills one can expect from a genre work. You won’t have a better time looking at someone else’s phone this year.

Grade: A-

Lester Scale: Classic

The Soderbergh Players: Interestingly, Soderbergh has ditched most of his repeat players this time around. The only main actor in the film who’s recurring from Soderbergh’s past work is Amy Irving (whose De Palma baggage is ultimately helpful to deciphering what this movie is going for) as Sawyer’s mom, having previously played wife to Michael Douglas and mother to Erika Christensen in Traffic. That being said, there is a cameo from an all-time great Soderbergh player in a flashback near the middle of the film. This person shows up to help Sawyer avoid her stalker, and their movie-star persona is a genius way for Soderbergh to hammer home the point that this kind of trauma cannot be easily sent away no matter how powerful the help is. Their casting is also accidentally prescient in another way, but saying more would almost certainly give their identity away.

Behind the scenes, there are a few more familiar faces, but perhaps most noteworthy are the people who don’t return for this. This is Soderbergh’s first film ever (including that Yes concert film) made without the help of sound designer Larry Blake, and his first film in decades without 1st AD/producer Gregory Jacobs (although they both get thanked in the credits). And for the first time since The Informant!, the production design isn’t done by Howard Cummings, but by April Lasky, who up until Unsane had only designed short films. The main ones who’ve stayed with Soderbergh on this little experiment (besides Peter Andrews and Mary Ann Bernard, of course) are his longtime casting director Carmen Cuba (who recently got some attention for her work finding unknown actors for The Florida Project, made by that other iPhone-using director) and costume designer Susan Lyall, who started on King of the Hill and eventually came back for Side Effects and Mosaic. And while this is technically cowriter James Greer’s first film for Soderbergh, they go way back, with Greer’s connections to Soderbergh’s favorite band Guided by Voices (including briefly playing for them and writing a history of them that Soderbergh contributed an introduction to) getting him a job writing Cleo, that batshit 3D Cleopatra musical with Catherine Zeta-Jones and Hugh Jackson singing Guided by Voices songs that fell apart in pre-production. Greer will return to the Soderbergh fold with Planet Kill, a secretive, apparently batshit-crazy sci-fi movie that Soderbergh may direct after the Panama Papers movie (so, three movies away, at very least).

And then there’s the matter of the composer. The film has a pretty lo-fi synth-and-piano score, not not one of the most memorable scores in the Soderbergh oeuvre, but it definitely gets the job done. But just who did the score? The name of the composer is not listed on the poster or in the opening credits, but is hidden away in the closing credits; David Wilder Savage. Except a Google search reveals that “David Wilder Savage” is not on IMDb, and his name is actually the name of a character in Rona Jaffe’s novel The Best of Everything. And a little bit more research (i.e. looking a little further down the first page of the Google search) revealed that this “Savage” character is actually a pseudonym for Thomas Newman, the legendary composer who worked with Soderbergh on Erin Brockovich, The Good German, and Side Effects. Newman was listed for a long time as the film’s composer on its Wikipedia page, but I’ve been burned enough by fake credits on Wikipedia pages that I didn’t trust it. If nothing else, this will teach me to never assume that someone working on a Soderbergh movie isn’t using a pseudonym.

Besides the Full Frontal clip, there are two other self-referential Soderbergh moments here that I want to point out. One is Soderbergh returning to the most famous location in Out of Sight, a car trunk, although here he has to shoot the scene in night-vision (non-diegetic night-vision at that; I was expecting the reveal that David was watching her with night-vision goggles, but nope, that’s just what Soderbergh needed to do to get her to appear on-screen). And the other is a reprise of Ocean’s Twelve‘s final shot, here with a completely reversed meaning (and Soderbergh lets it play over the credits, a wonderful 70s touch in an otherwise aggressively modern-looking movie).

Up Next: Well, I guess I should probably get to covering season 2 of The Girlfriend Experience at some point (I’m not going to cover the TV version of Mosaic, though). After that, maybe I’ll cover Criterion’s forthcoming edition of sex, lies, and videotape, since it almost certainly will have Soderbergh’s long-lost short Winston on it.