NOBODY WAS ROBBED DURING THE MAKING OF THIS FILM

EXCEPT YOU

A month before Behind the Candelabra would become his “final” film, Steven Soderbergh addressed the crowd at the San Francisco International Film Festival about the “state of cinema”. This speech would become his de facto pre-retirement parting thoughts, and they explain why he felt the need to retire from film. He talks about studios killing creativity in one way or another and spending money in all the wrong places, with absurdly inflated ad budgets and less creative freedom for directors. Now, in the words of the Gandhi II trailer, he’s back, and this time, he’s mad.

Logan Lucky comes as not just Soderbergh’s triumphant return to filmmaking, but the first product of a new gamble from him, a studio run the way Soderbergh believes one should be run. Under this system, Soderbergh gets approval of all ad materials, he and his actors get 50% of the profits (which will be easily accessible in a password-protected account), and he gets to keep his budget as low as he needs it to be (i.e. no $20 million ad campaign). If this film succeeds (which, uh, I’ll just say the opening-night audience I saw it with does not suggest that outcome), it will be a massive blow against the stodgy studio practices that Soderbergh said four years ago weren’t getting results. If it doesn’t, Soderbergh will probably survive (for fuck’s sake, he made a whole other movie on his iPhone while finishing this one). But with that all out of the way, is the film he chose to inaugurate this new approach with worth its weight in salt?

More than any other films in his career, the Ocean’s movies (and Eleven in particular) seem to haunt the public’s perception of Soderbergh. Here is a man who gave the public six hours of movie stars at their most charming, and who stubbornly refuses to give that to them again. He’ll give you movie stars, but they’ll be flabby, mentally ill, silently brooding, complicit in the atrocities of the Holocaust, or dead and getting their head sawed open before they have five minutes of screen time. He’ll get you action, but it will either be ruthlessly deconstructed or surrounded by impressionistic glimpses at a communist revolutionary. And thus, so many of Soderbergh’s following films were roundly and loudly rejected by audiences even in the face of critical acclaim. Perhaps him coming out of retirement to make the one film of his that can and has been straightforwardly compared to Ocean’s Eleven and beyond could be seen as a sign of defeat, a return to safe pastures. That maybe holds up as a premise until the second you start actually watching the movie.

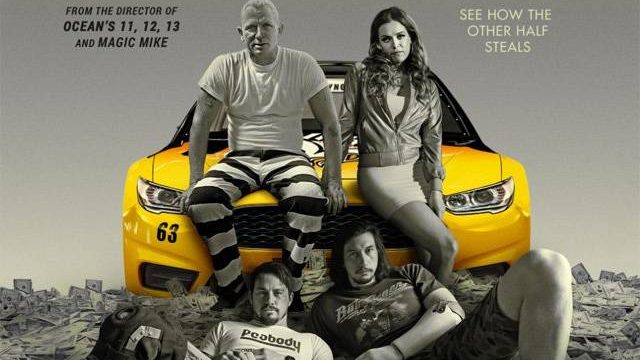

Jimmy Logan (Channing Tatum) is what you might call, in all its positive and negative connotations, a “good old boy”. He’s a West Virginian, working construction in Charlotte, North Carolina when someone spots him limping (he blew out his knee in a football injury when he was a teen) and gets him fired for failing to disclose a preexisting condition. As if that wasn’t enough, his one-armed Iraq vet brother Clyde (Adam Driver) keeps blathering on about a supposed family curse, and his ex-wife (Katie Holmes) is planning to move with their daughter Sadie to Virginia, which would put a damper on his custody days. What’s a guy to do? As the simplest answer is often the best, he decides to plot out a ten-item robbery checklist (“shit happens” is on it twice) and propose robbing Charlotte Motor Speedway, based on an on-job discovery he made of the tubes that carry money into the Speedway’s vault. But he needs a team, and in lieu of a Danny Ocean-style exhaustive talent search, he recruits Clyde, their sister Mellie (Riley Keough), imprisoned demolitions expert Joe Bang (Daniel Craig), and his knucklehead brothers Fish and Sam (Jack Quaid and Brian Gleeson). Will this ragtag bunch get Bang in and out of prison and pull off the heist? Will Jimmy find love with a health-care provider and former high-school flame (a short-haired Katherine Waterston)? Is Seth MacFarlane doing a British accent solely as a dare to do a worse one than Don Cheadle did in the Ocean’s movies?

Ocean’s Eleven is a Swiss watch of a movie, elegant and beautifully-constructed. Pulling that exact combination again would probably seem less cool and more tiresome in a follow-up, and it’s a testament to Soderbergh’s judgment that he realized that would be the wrong way to make Ocean’s Twelve and even the “back-to-basics” Ocean’s Thirteen. Now, the connections to Eleven (even acknowledged in the film proper, with a news report dubbing the heist “Ocean’s 7-Eleven”) had me thinking that this would be a return to that kind of moviemaking after Soderbergh let it stand on its own for 15 or so years. I am incredibly pleased to report that it’s not that at all, and if anything, it borrows more from Twelve‘s go-for-broke approach (albeit without that film’s alienating weirdness). This is a heist movie with strange rhythms. It starts out slow, to quietly build the characters and set up the groundwork for what’s to come, hardly a new thing in this or any genre. But once the movie starts ramping up, Soderbergh (and that elusive Rebecca Blunt) revel in hitting the brakes at full force for minutes at a time. Sometimes this is clearly motivated, as in Waterston’s extended introductory scene setting her up as a love interest, or in the film’s funniest scene, which shows the lengths Joe Bang’s fellow prisoners go to stall while he’s off on the heist. But other times it’s on the surface completely unnecessary, like when a small player in the heist basically gets an entire short film just about her as opposed to the quick montage she’d be relegated in an Ocean’s movie, or better yet, when a minor race-driver character (played by Sebastian Stan) gets a Terry Valentine-esque trailer montage depicting his rigorous ways of healthy living (he calls his body an “operating system” and the food he eats “software”). At first blush, this might seem like needless padding (the movie runs just under two hours), but as the film goes on, it becomes clear that these weirdo detours are merely part of Soderbergh’s devotion to the one big rule of heist movies; we care about the characters more than the heist. Here, while the heist is the centerpiece of the film (and an absolute joy to behold), it’s merely an anchor for a sprawling, loving character study of even the smallest roles in the film, which becomes increasingly clear the further the movie stretches past the heist. It’s maybe as compassionate a movie as Soderbergh has ever made, where every day-player has a story and most have a heart of gold. It even sidesteps the possible “big city folk mocking rednecks” angle by clearly admiring and loving all of these people and allowing them to be as smart and capable as the movie stars in suits (admittedly, Quaid and Gleeson are not very smart, but they’re the exception rather than the rule, and they’re also fucking hilarious in this; they get some great Coen brothers/Schizopolisian word games throughout). The only “bad guy” in the movie is the outsider, MacFarlane’s obnoxious, self-promoting energy-drink peddler, and even he’s more a very minor nuisance than anything too mean-spirited (even the deliverer of Jimmy’s firing, played by Parks and Recreation‘s Jim O’Heir, is not played for “unfeeling hand of the free market” vibes like, say, Betsy Brandt in Magic Mike).

Helping the film’s humanism a great deal are the performances. Channing Tatum has been, under Soderbergh’s lens, a kind of avatar of decency (it’s even kind of a sick joke in Side Effects, where his insider-trader is still by far the most sympathetic of the leads), and he’s never been warmer or more decent than he is here. It’s not a showy part, but it’s a genuinely moving one, and a very necessary one for Soderbergh’s approach here. That he’s often been ignored or not singled out as a highlight is just a testament to how good everyone else is in it. Adam Driver continues his knack for underplaying here, with Clyde making the least of even life-or-death situations (the way he ever-so-calmly prepares a Molotov cocktail is beautiful) while remaining sometimes painfully human (just look at his reaction when he loses his prosthetic arm during the job). Riley Keough is an absolute joy as Mellie, who makes up for Jimmy and Clyde’s lack of energy with aplomb (and not just when she’s behind the wheel and breaking the speed limit). Seth MacFarlane admittedly tows the line with his schtick (and again, his “British” accent is even worse than Don Cheadle’s), but you also get to see him get the shit beat out of him, so it evens out. And even the smallest parts are filled by great actors doing great work, from Waterston and Stan to Dwight Yoakam as a prison warden eager to wash his hands of everything that happens in his prison to Hilary Swank as a tough FBI agent investigating the heist and, wonderfully and improbably, Jeremy Saulnier’s sad-eyed muse Macon Blair as her straight-down-the-middle partner. And of course, there is Daniel Craig. He’s advertised as being “introduced” by this film, and he really might as well be, because this is utterly unlike Craig’s normal forte (even outside of Bond) as the stern, brutish force of violence. Joe Bang is, from his name down to his squeaky Southern drawl, a cartoon, and Craig leans into this ridiculousness (he even takes time in the middle of the job to literally write out the formula explaining the explosives he’s prepared) with pure glee. He may be coming back for another round in the Bond cage, but I do hope he takes some of the energy uncovered here back there. He doesn’t have to laugh maniacally while offering someone a prosthetic arm, but that wouldn’t hurt either.

I hope I don’t need to tell you that Soderbergh directs the hell out of this movie, but I should mention the ways in which he does it. This is maybe the most stylistically restrained Soderbergh has been in a long time. Gone are the flashy, splashy camera movements and in-camera colors of Soderbergh, sorry, I mean Peter Andrews’ work on Magic Mike XXL, the weaponized natural lighting of The Knick, Side Effects, and Behind the Candelabra, and, most shockingly, the overt color grading of all of his post-Kafka work. There are occasional forays into orange (all in interiors, including the bar where Clyde works and the child beauty pageant where Sadie completes), but mostly, the light here isn’t that or blue or yellow, but honest-to-god white, shining down peacefully and unobtrusively on these characters. And beyond that, Soderbergh relies surprisingly little on the score from the returning composer from the Ocean’s movies, David Holmes, here, and not in a Haywireian deconstructive way (Soderbergh mostly fills the soundtrack with a lot of 70s needledrops, including the mother of all obvious ones, “Fortunate Son”, plus a John Denver one that could make a stone cry). But if all that windowdressing is gone, that just leaves Soderbergh’s typical formal mastery left bare for all to see. His compositions are always on-point, often getting laughs solely from a character’s position from an object, and they frequently play with focus in quite fun ways (like one bit where a door not working is conveyed by the door latch repeatedly coming in and out of focus). The heist itself is beautifully-constructed, but the film is full of beautifully-constructed little scenes, including the aforementioned character montages, plus the expected bit of chronological monkeying, a prison riot staged like a song-and-dance number (maybe Magic Mike XXL was more important to this than I gave it credit for being), a bar fight told as quickly and in as few shots as possible, and most unexpectedly, the one good and moving example in god knows how long of the “dad just barely makes it to the recital/play/pageant” trope. If Soderbergh only came back to take the hoariest idea in all of cinema and give it new life, he did a good thing.

Soderbergh has said that he doesn’t want to make “important” films or ones only a few people can understand in this post-retirement phase of his career. But if that sounds like he’ll be strictly playing it safe from now on, Logan Lucky thoroughly puts the lie to that notion. This is great entertainment, and it’s great Soderbergh. That being said, fuck that shit, Soderbergh, why would you want to entertain millions when you can entertain literally only me and make Son of Schizopolis? Fuckin’ total disregard.

Grade: A-

Lester Scale: Classic

The Soderbergh Players: The current MVP for Soderbergh’s “rushing to retirement and back” period is undoubtedly Channing Tatum, making his fifth appearance in a Soderbergh film here (yes, Magic Mike XXL absolutely counts). But he better watch his back because, fitting considering she plays a speed-demon in this, Riley Keough is gaining on him. This is her third work with Soderbergh, following a mostly silent role in Magic Mike (where she nonetheless gets an incredible, movie-star-is-born introductory shot) and the quietly incredible lead performance in the Soderbergh-produced first season of The Girlfriend Experience (btw, I’ll be a doing full review of the next season whenever that comes out). Aside from those two, this cast is actually very light on repeat players, unless you count Katie Holmes’ cameo in the upcoming Ocean’s Eight.

The usual suspects for Soderbergh’s technical crew are all back. Obviously, Peter Andrews and Mary Ann Bernard have come crawling back with him, and so has the aforementioned David Holmes (who’ll also be scoring Mosaic), production designer Howard Cummings (who’s worked on The Underneath and everything after Haywire), producer Gregory Jacobs (although he’s finally taken a break from being Soderbergh’s first AD), and sound guy Larry Blake, who’s been with Soderbergh since that Yes concert film (here, he graduates from “supervising sound editor/rerecording mixer” to the catch-all “sound designer”). There’s also fellow producer, and Barry Levinson’s right-hand man, Mark Johnson, who’s working with Soderbergh for the first time since Kafka (after Soderbergh’s attempt to make Quiz Show for him was mooted)

There are also some Soderbergh trademarks/in-jokes thrown in that I didn’t see fit to include in the main piece. The big one, and the one that almost made me go insane in the theater, is the company name “Perennial”, which Soderbergh used in The Underneath, The Limey, Traffic, and now this (it’s the name of a gas station here). There’s also the gag of Sebastian Stan’s NASCAR driver being sponsored by Singani 63, even driving the 63 car (it’s also a reference to Soderbergh’s birth year, 1963), and the logo of Soderbergh’s new distribution company, Fingerprint Releasing, being a wonderfully obvious rip-off of the Saul Bass Warner Bros. logo animation, used to open both Magic Mikes. And before the wonderful note quoted at the top of this review, there’s the always reassuring note of this film having been rerecorded in a Swelltone theater. Well, it’s reassuring to me, a fucking weirdo loser, at least.

Up Next: I know I’ve been saying this for the past year and beyond, but Soderbergh has said Mosaic will be coming out in November, so I think next will be Mosaic. Either that or The Girlfriend Experience season 2.