“The child is the father of the man” — William Wordsworth

The Coen Brothers do not care for children. They have use for babies, but that is because babies are more objects than people and make excellent symbols and metaphors and plot devices — hope for the future in Fargo and The Big Lebowski, regret for the road not taken in Inside Llewyn Davis, adorable MacGuffins in Raising Arizona — but not characters that can be given action and, more importantly ,dialogue.

Actual children, who can speak and act, are few and far between in their movies. Their one explicit child protagonist, Mattie Ross in True Grit, is essentially an adult in all but age (she’s more mature than 95 percent of people in Coen movies) and is mostly the creation of author Charles Portis in the first place. So what to make of Danny Gopnik?

As a teenager in a Minnesotan Jewish community in the late 60s, he’s easily the closest to an autobiographical character the Coens have ever put on screen. There’s only so much to read into this, I think: the Coens were making movies as precocious teens and young Danny is a feckless pothead who loves watching F Troop but never shows any inclination toward creation. His background is a way for the Coens to write a convincing young person, a window to verisimilitude. And getting him right is important — if he is not the protagonist, he is the co-lead of the movie, the one who ties everything together.

Excluding the prologue, Danny is the person who opens and ends the movie. The story begins in Danny’s head as he rocks out to the Jefferson Airplane via earpiece and radio in an exceedingly boring Hebrew class. A nearmatch cut to his father Larry getting his ears checked as part of a physical is the first of several moments tying together the father — the movie’s ostensible protagonist — and the son. But while Larry, a teacher, goes through an existential crisis of escalating and insoluble problems, Danny, a student, has only one real concern: not getting the crap pounded out of him.

After the Airplane crashes into the classroom via a ripped-away earpiece, Danny’s Hebrew teacher confiscates his radio and its carrying case. Said case contains a 20 dollar bill intended for one Mike Fagel, whom Danny bought a lid of weed off of a short while ago and has not yet paid back. The moniker “Fagel” is not dissimilar to the Yiddish homosexual insult “faygele” but Mike, played by Jon Kaminski Jr., would never be called that by a person who wanted to keep his teeth — he is a massive squarish slab, slow and silent and inexorable, who is known for beating up people who have not met his terms. In short, he is a golem, a monster with a singular purpose, and that purpose is getting the money he is owed.

The Coens have a lot of fun with this, staging increasingly tense and hilarious scenes where Danny gets off the bus from Hebrew school and runs for his life as Fagel sluggishly pursues him to his house, escaping by the skin of his teeth while Fagel glowers from the sidewalk.These scenes are consistently shot from behind Fagel. We don’t need to see his face; menace radiates from his hunched and powerful back. He is terrifying in the moment, but the very physicality of his threat makes it less powerful than Danny’s father’s ongoing spiritual crisis.At least Fagel can be grasped, grappled with. And Danny sort of has this coming to him by not paying Fagel back sooner. As his father tries to explain to a failing student, actions have consequences. If a beatdown is all Danny has to fear, his life isn’t too bad.

What we see of Danny’s life through the course of the movie bears that out. He spends a fair amount of time getting high with his idiot friends, who have taken to curse words in the enthusiastic and unsophisticated way only 13-year-olds can — one speculates on the teacher who confiscated Danny’s radio, concluding “Maybe the fucker lodged it up his fucking asshole! Waaay up his asshole!” The Coens will write delirious stylized dialogue when it fits but they also have an understanding of stupidity’s cloddish lexicon and they deploy that brilliantly here. If language is a holy gift that separates man from the animals, what Danny and his friends are doing with it is more profane than any pea soup-puking demon could imagine. And Aaron Wolff gives no hint of precociousness in his performance: he is occasionally kind and not a malevolent kid, but he is callow in the extreme, concerned about the pettiest of things while the adults deal with the real stuff.

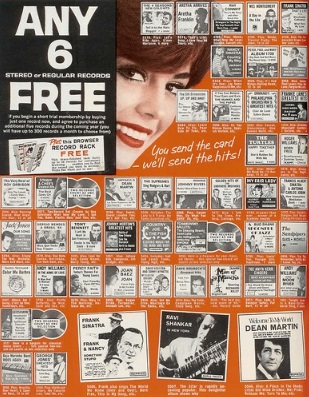

Did someone say petty? Danny is devoted to the sitcom F Troop, constantly badgering Larry to fix the aerial on their roof so he can get better reception. As far as Danny is concerned, the best part of his father and mother getting back together after a brief separation will be a less fuzzy Larry Storch. And he listens to the hallmark of any movie set in the late 60s: rock music. As Larry learns to his chagrin, Danny is a non-dues-paying member of the Columbia Records club, presumably listening to but not sending the requisite cash for Santana Abraxas and Cosmo’s Factory in addition to his spinning of Surrealistic Pillow.

What Danny is very much not interested in, aside from some half-hearted practice chanting to the Hebrew records in his collection, is his upcoming bar mitzvah. The ritual where, according to Jewish tradition, he becomes accountable for his actions, where he becomes a man. What we see suggests that man will be less than serious. The movie’s bravura sequence is the bar mitzvah ceremony itself, in which Danny is cataclysmically stoned (a reaction shot of his equally baked friend is the biggest laugh in a very funny movie) and barely functional, requiring rabbinical assistance to feed him his lines and remind him to not step on the kiddie stool at the lectern. But Danny muddles through and what puts this scene in the same league as the KKK dance-off in O Brother, Where Art Thou? or the convenience store coin flip in No Country For Old Men is the co-equal emotions clashing — Danny’s dopiness is hilarious but that does not negate the pride of his oblivious father and mother watching from the benches below, estranged yet reconciling for a moment in the hope of a new generation. Danny is baffled but moving forward because it’s what’s expected, the son following in the steps of his father, and that connection has truth despite the often foolish actions of the men on either side of it.

Mother Judith and sister Sarah* don’t get a lot of play here. Sarah is always washing her hair on her way out the door to hang with her friends and Judith is mostly a shrew whose anger at Larry is vicious and manipulative but also understandable in the face of his passivity. This is the story of Larry and Danny, who echo and mirror each other, starting with how both of them always arrive home from school/work at the same time. And they both deal with the threat of physical violence and pressuring, Larry’s coming from the angry goy neighbor next door and from the oleaginous Sy Ableman (Sy Ableman?!)**.

But there are missed connections too. Danny is a veteran of getting high who could have helped Larry during his one experience with “the new freedoms.” He also has a closer relationship than Larry does with Larry’s brother Arthur, whose “mentaculus” system provides gambling winnings that the indifferent Arthur gives to Danny, who uses them to buy weed. And while Larry has several disturbing dreams that might explicate his desires or give clues to his inner turmoil, he never turns to his son — named for the interpreter of dreams — for guidance or even a friendly ear, a perspective outside of his self-serious contortions.

The irony is that Danny, not Larry, finally meets the much-sought-after Rabbi Marshak, coming face to face with the learned man after he becomes a man himself. Larry has been seeking guidance from Marshak for nearly the whole movie and never receives it; being turned away at the precipice by one of the stocky, stoic Jewish women whom the Coens see as actually running the community. Larry is looking for someone to explain things beyond his ability to comprehend, when Danny does meet Marshak as the culmination of his bar mitzvah, he receives words of wisdom he already knows: “‘When the truth is found to be lies and all the hope within you dies’ — then what?”

Marshak has been listening to Danny’s radio and can name the members of “the Airplane.” He sees a value in this music that Coens slyly agree with. Much of the non-score songs in the movie are diegetic, but the lengthy Goy’s Teeth tale, a shaggy dog story within a shaggy dog story that is presented as the inexplicable and incomprehensible interference of Hashem, is soundtracked to Jimi Hendrix’ “Machine Gun.” Is rock music an insight into or accompaniment for the divine? Danny hears and doesn’t know; despite Danny’s accidental influence, Larry refuses to hear. He doesn’t want Santana Abraxas, Abraxas of course being another word for god. Larry refuses to take what his son has already given him.***

Marshak’s explicit advice to Danny is simple enough: “Be a good boy.” Questionable advice for a new man, but Danny isn’t interested in that. He’s much more enthusiastic about Marshak returning his radio and its concealed $20. Finally, he can rid himself of this golem’s unending pursuit! And so we return, as we have in many Coen movies, to the beginning: Danny is at Hebrew school, preparing to pay off Fagel, and Larry — after deciding to accept a bribe**** — is about to get some information from his doctor. But that information is clearly bad. And class is being interrupted for a tornado warning.

The class stumbles outside, excited to not be memorizing Hebrew in a stifling room, but nervous about the darkening skies. The teacher can’t unlock the tornado shelter. The students mill about a parking lot and Danny sees his chance, pulling out the twenty dollars and yelling “Fagel! I got your m—” and stopping as Fagel turns around. It’s hard to describe the look on Fagel’s face as he looks at Danny, as he looks at the viewer — there is awe and terror and contempt and maybe astonishment as he regards Danny and us. It’s a look that knows being responsible for your actions does not mean there aren’t things beyond those consequences, that to live in the world means living without a roof and an aerial over your head, without a father who can tune the reception just right, maybe even without a Father from whom you can beg and plead mercy.

Then Fagel turns his head to look back at the funnel that is consuming the horizon, a force well beyond any single human pounding the crap out of another, a wrath that cannot be bought off with twenty dollars. In the end, the Coens have no use for childish things. Danny is now a man and facing not only death but annihilation, the howling void, and the fact that he is not alone in doing so is not much consolation. He isn’t prepared — are any of us? All he has is a double sawbuck and a radio that even now is plugged into his ear. Unlike Larry, he’s set to receive. And the Coens finally treat him like an adult, that is to say, they set him up for a punchline instead of making him a joke. At the end of all things, when, if nothing else, the final answer arrives, Danny is instead given a question: Don’t you want somebody to love?

*There is a whole backstory encoded in these names, Judith and Sarah and Danny are solid Hebraic history, but Lawrence and his brother Arthur are Anglo/Christian as hell — what is Larry compensating for? Reacting against?

**More with the names — Abel man? The original smarmy suck-up, the victim who had it coming?

***As a person who was ripping off Columbia Records and BMG Music 30 years later, with my parents stuck with the bill, I can empathize with Larry here.

****The tornado warning comes before Larry’s decision — an omnipotent being can of course manipulate time but I generally dislike the idea that Larry causes the tornado. Aside from the reasoning above, it’s a lot of destruction of randos just to screw Larry over and while that’s never stopped a vengeful god before, it doesn’t fit with the specific illness/health issue that would also be punishment for Larry. This belongs to Danny.