First, a confession: I really enjoyed Joe Wright’s much-maligned adaptation of Anna Karenina. Yes, Tolstoy would have hated it (especially the later Tolstoy, who also hated his own novel), and yes, it does nothing to engage with the moral and spiritual issues of the novel in any meaningful way, but I greatly appreciate its commitment to its aesthetic vision, and as a consequence, its sense of play with the artificiality of social behavior in the novel’s milieu (albeit an insight better suited to a different classic Russian novel.) If anything, the friction between Tolstoy’s vision and Wright’s is part of what makes the work so compelling to me: it’s not that Wright tried and failed to be faithful, but that he took faithlessness as an aesthetic point of departure and found something interesting in response.

So why does the also-unfaithful The Brothers Karamazov fail so badly? It, too, consciously departs from the novel by reducing Dostoevsky’s sprawling narrative into what is essentially the story of one brother, Dmitri. Its screenplay was written by Hollywood adaptation royalty, the Epstein twins (Casablanca, Arsenic and Old Lace), and by multi-hyphenate Richard Brooks (Blackboard Jungle, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof), who also directed. Its visual style is also a thoughtful one, as I’ll detail below. But it fails in the most basic act of adaptation: after those crucial decisions about what to keep and what to cut, the Whole has not been reimagined around what remains. In other words, the movie dramatizes one of the novel’s plots but makes very little sense as a thing-in-itself.

The Plot

Of Dostoevsky’s major novels, The Brothers Karamazov is the least-suited to adaptation. The other three all contain some central core around which all the characters and plots revolve: the cat-and-mouse of Crime and Punishment, the charismatic void Stavrogin in Demons, the fatal love triangle of The Idiot. For these three, an adaptation could safely shed subplots and characters without disturbing the overall design. To the extent that Karamazov has a core, it’s an abstract one, and much less severable from its parts.

Very briefly, the seemingly messy architecture of Karamazov, which involves multiple family histories and flashbacks, two or three overlapping love triangles, incessant monetary and legal wrangling, and entire sections given over to debates on religion, freedom, and responsibility, are all part of Dostoevsky’s grand design for justifying a fairly contrived climax: how a murder trial could arrive “rationally” at the wrong verdict, while the “irrational” testimonies reveal the actual truth (both small-t and capital-T). Every character and every plot converges here, a test of faith against a newfangled invention that Russia had just imported from the West: trial by jury.

I call this “contrived” because Dostoevsky has to go to very great lengths to make his setup seem both extreme and plausible: the would-be murderer is seen holding the murder weapon and saying “I will murder you!” to a man who is murdered a few moments later, and all this is weighed against the testimony of a town doctor who remembers that the would-be murderer once thanked him for a pound of nuts he gave him for learning a prayer in German… Look, it’s a great book, but it looks silly when you explain it in a straightforward way, thus Dostoevsky’s very rambling, very digressive narrative that spends some five or six hundred pages putting all the necessary pieces into place. Crucially, we are not present at the moment of the crime, but have to reconstruct the story on the basis of testimony: the novel tests us, as well.

From here we can already see why cutting everything but Dmitri’s arc creates such a problem for the filmmakers. For one thing, the novel’s messy architecture is tied both implicitly and explicitly to its moral themes, so cutting out two (really, three) legs of the fraternal stool causes that conceptual structure to collapse. It makes good sense to re-center the story around Dmitri, at least in theory, since Dmitri is the only one of the brothers whose mode is primarily active: the rest sit and talk, and talk so more, and keep on talking. But when the latter three do have to act — when Alyosha has to test his faith, when Ivan’s mental conflict spills over into madness, when Smerdyakov plays his peculiar part in the drama — they’ve been given little to no material for motivating or explaining their behavior. The devil, alas, does not make an appearance.

Worse, the few nods to their ideological content feel flippant at best: the movie’s Ivan, for example, has a tendency to walk into a room and say, unprompted, “Hello: there is no God”; the book gives us a three-chapter-long (!), tortured manifesto of atheist rebellion, and the lack of anything of comparable weight (or of any weight at all) makes Ivan’s ultimate actions in the movie seem almost comically unmotivated. The central moral figure in the book, Father Zossima, has about two meek lines in his minute of screen time. Dostoevsky considered Zossima’s chapter the most important in the novel.

And still… still, some of this might have worked if the remaining scraps had been stitched together with some kind of vision, but the film does little more than illustrate scenes from the life of Dmitri. This extends even to the finale, which reverses a key argument of the book. Dostoevsky’s bold final gambit, using a senseless tragedy to challenge his readers to embody the same kind of faith of its characters, is completely neutered here, leaving us with an amateurish life lesson about good people doing good deeds, etc. etc. It’s a shrug of an ending.

The Performers

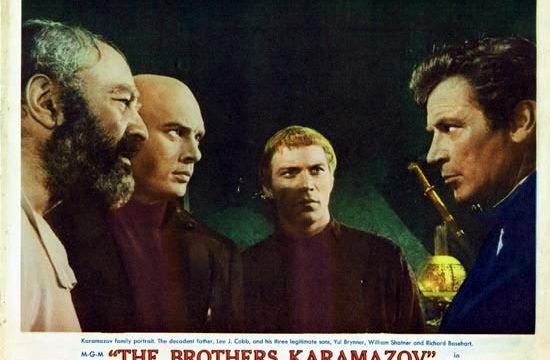

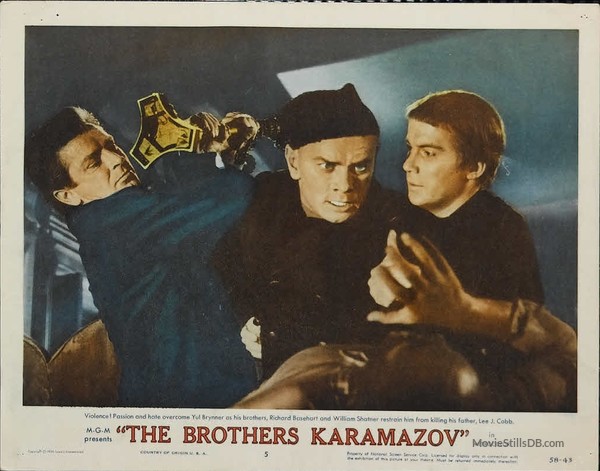

But this is just the narrative, and movies are (thank god) more than just narrative. Some of the performances, for example, add nuance otherwise lacking in the screenplay. There is Lee J. Cobb’s Oscar-nominated turn as the father Fyodor, less the sly and repulsive buffoon of the novel and more a violent creature of perverse bodily cravings, someone who, unlike Dostoevsky’s craven Fyodor, we can easily imagine punching back. There’s a magnetic Yul Brynner playing Dmitri as pure sexual id, though he lacks the novel’s sense of a childlike innocence under the skin, which only becomes a problem in the final stretch. Maria Schell’s much-derided performance as Grushenka won me over her sphynxish smile, the ambiguity of whether she is, at any given moment, sincere or merely toying with the people around her; Claire Bloom makes a good foil in the proper but obsessed Katya, though her part is whittled so far down from the novel that her infatuation with Dmitri reads even more hysterically than in Dostoevsky (a writer whose women aren’t exactly unknown for their hysterics). Still, she carries most of the weight of this on her face, and it’s an effective performance despite the screenplay.

It’s the three other brothers where the problems arise. Today, William Shatner would be nobody’s choice for an adaptation of a classic Russian novel, but the best that can be said of his Alyosha is that he does what the screenplay requires, which is very little. Richard Basehearts’ Ivan seems imported from another movie, which is fitting enough for the character, an outsider who feels superior to everyone in the grubby town, but only exacerbates the sense that his role in the narrative is only a vestigial residue from the original work. Meanwhile, Albert Salmi’s Smerdyakov seems imported from another planet. To be fair, it’s hard to imagine many actors grappling convincingly with the novel’s most enigmatically evil character — Smerdyakov is a void, a reflection of other people, an idiot lackey in public and a sociopath underneath — but the film seems entirely at a loss about how to handle him, and Salmi offers nothing to compensate apart from a stiff weirdness.

The smaller roles are equally hit-or-miss. Some older actors come through with their dignity intact, especially David Opatoshu and Edgar Stehli, both playing victims of Dmitri’s rage. Judith Evans is just sort of there as Madame Hohlakova, another pointless vestige. And then there’s Miko Oscard as the pitiful Ilyusha, a character vital for the novel’s ultimate argument about faith and responsibility. Child actors were routinely dubbed in classic Hollywood, but the effect here is so grating that I can’t imagine how contemporary audiences dealt with it. The overall effect far overshoots pitiable and lands somewhere in uncanny, unintentional comedy.

The Production

Finally, I want to talk a bit about the production, which is one of the areas where the film enjoys its greatest successes (though even here, not consistently). The score, by Polish composer Bronislau Kaper, is excellent, especially the title track, which gives us clashing bells, savage strings, and chunky piano chords all straight out of Russian modernism before suddenly leaping into an authentic gypsy song, “The Pacer,” covered by the Dimitrievich sisters Valya and Marusya (Brynner was a friend of the family and later recorded an entire album with brother Alyosha). Kaper’s thoughtful use of motifs does more to tie the movie together coherently than any other aspect of the production.

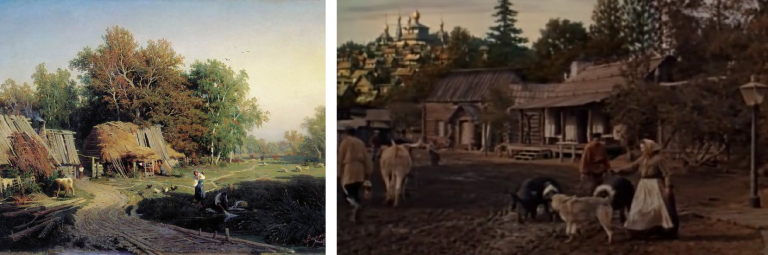

There’s also a keen eye for visual design, at least in some cases. While the music is unapologetically modern(ist), many of the exterior scenes seem designed to reflect a certain style of 19th-century Russian painting associated with the Peredvizhniki, a group of artists whose name is usually rendered in English as “the Wanderers” or “the Itinerants”. This is an astute choice: Dostoevsky was their contemporary and openly wrangled with the aesthetic and moral dimensions of their art. Here, for example, is an 1869 painting by Itinerant painter Fedor Vasil’ev alongside a still from the opening shot of the movie:

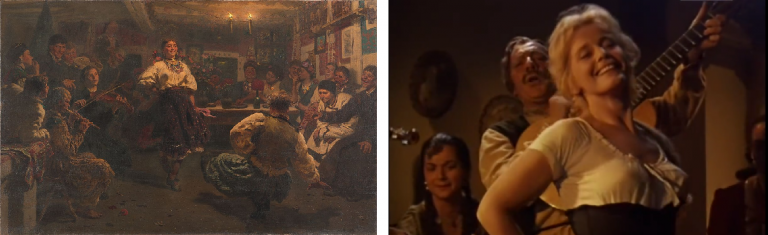

Even some interiors reflect the complex realist/romantic gaze of the Itinerants, like this 1881 piece by Ilya Repin, alongside Grushenka’s intoxicated/intoxicating dance:

Unfortunately, the production sometimes alternates these with more conventional film interiors, anonymous rooms and settings that seem to be borrowed from other films, creating a confusion of spatial logic, and that confusion extends to other aspects of the production, as well. The apex of this is the ice-skating scene. I don’t know what it is about Dostoevsky adaptations and creepy ice-skating (see also: the weird-as-fuck scene in Kurosawa’s The Idiot, which has costumed children skating to the tune of Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain, what the hell?), but even here, the otherwise electric, erotic tension between Brynner and Schell, already a touch off-kilter in both dialogue and affect, feels strangely accented by bizarre production choices, such as Brynner fake-carrying Schell on what must be a mechanical rig of some sort. Whatever romantic or erotic elements the scene is going for, the actual result feels uncanny and confusing.

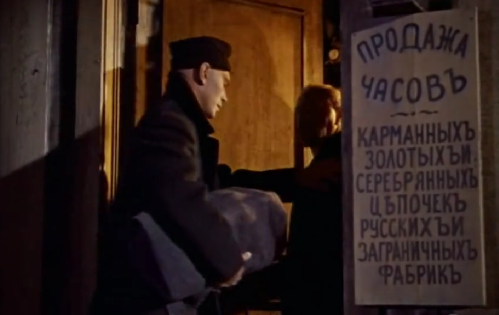

On a final note, I can’t resist highlighting one of the movie’s most confounding images. Most of the film’s on-screen language is in English, like wooden directional signs that show us the town’s name, Ryevsk (losing Dostoevsky’s much funnier Skotoprigonyevsk, or Stockyard-Town, funny because his narrator also dismisses the townspeople as “cattle”), or the site of Ivan’s bacchanalia, Mokroye. Yet we also have this storefront sign, which is written not only in Cyrillic, but in pre-revolutionary orthography, i.e. the alphabet used before the writing system was reformed in 1917:

This is a hilariously pedantic choice for a Hollywood film that otherwise amputates the source material down to a barely functioning set of organs and limbs. Why did they do this? Why bother with this level of detail, especially since the other signs are written in Latin letters? Who’s even going to care about the sign when everything happening around it is so confounding?

Why did they do this?, a question I must have asked myself a dozen times watching this movie. Certainly not what Dostoevsky intended with his novel, but neither is it a compelling hook for an unfaithful adaptation. Brooks’ The Brothers Karamazov is a one-legged stool, and there are moments where the talent behind the production is undeniable, but in the end, there’s just no way to sit on it.