JB: Noir has always challenged dominant cultural values, and, at times, can capture the light and heat when social systems start to break down. In 1950, the threat of imploding families had become a national security risk, for domesticity was a cornerstone of the Cold-War policy of containment: the libidos of men and women were to be sublimated into stable heterosexual marriages, to keep both men and women from straying, and to prevent the worst-case scenario of their becoming Communist dupes.

Regardless of the flimsy rationale, domestic containment signified the prevailing ethos of social conformity, where any non-work-related activities outside of the home could be viewed with outright suspicion. Noir subverted these expectations for post-war pleasures to be exclusively reserved for the home. For example, there were the bitter outbursts of loner artists, such as Dix Steele, the PTSD-affected writer played by Humphrey Bogart in A Lonely Place (1950). How could, this film asked in a rather hard-boiled way, returning veterans fit in with a society ready to move on from the wartime images of men having to do what they had to do?

When veterans did have families waiting for them, they were compelled to become successful breadwinners, to ensure that their wives could devote themselves to their domestic responsibilities. In 1950, The Breaking Point and Try and Get Me! raised discomforting questions about the viability of domestic containment. In a manner that would surely rankle the “better-dead-than-Red” crowd, these two films connect post-war disillusionment about social progress to economic hardship in narratives about desperate men.

In The Breaking Point, the brooding look of John Garfield, as Harry Morgan, into a mirror conveys the distance he has traveled from being a decorated wartime killer to a struggling boat captain. Throughout the film, the reconciliation of two diametrically-opposed imperatives – maintaining his autonomy while financially supporting his family – leads him into dangerous waters. What may first appear as melodramatic family scenes, with an unmistakably erotic charge between Harry and his wife, Lucy, cranks up the noir intensity. We get how much he has to lose.

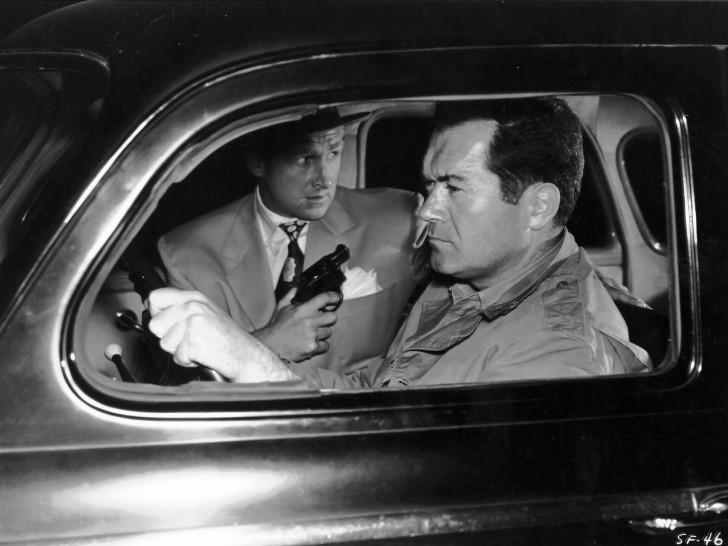

Try and Get Me! is more traditionally formulaic in depicting an economically- impoverished family. The unemployed, luckless Howard Tyler meets Jerry Slocum, a charismatic small-time crook, who talks him into becoming his getaway-car driver. A few holdups later, and it looks like Howard and his family are on Easy Street. But Jerry has bigger plans, and soon Howard is an accomplice to a brutal murder. In depicting the consequences Howard must face, the film steadily builds paranoia about what desperate men will do for the survival of their families, and the conservative backlash it can provoke.

While I’ve outlined how The Breaking Point and Try and Get Me! stage what could be called (then and now) a Marxist critique of the economic underpinnings of domestic stability, could you talk more about how the “Red Scare” in Hollywood provides a historical context for viewing the two films?

SoG: While both films harbor some residue of the 1930s Hollywood left, It feels like a bit of a stretch to call them Marxist. Rather than underscore capitalism’s systemic inability to support the hetero-normative family model, they utilize progressive-era social deviance models to emphasize their protagonists’ personal crises. Harry Morgan extends considerable capital on a fishing vessel that promises little profitability. His occasional heavy drinking and eye for the comely Patricia Neal opens the door for moral turpitude and questionable judgement. Try and Get Me!’s Howard Tyler is a bit more of a proletarian “everyman”. His limited skill set curtails viable employment opportunities. He takes whatever blue-collar jobs, like a factory watchman, that come up and abruptly go away. Feelings of professional inadequacy erode his sense of masculine self confidence, making him susceptible to the bullying of the psychopathic Jerry Slocum, who goads Howard into a life of armed robbery, kidnapping, and murder.

These films, I’d depict a more diverse range of progressive interests among the Hollywood left than historical materialism. Psychological naturalism more aptly describes these efforts. Before going into that, however, I should discuss why Tinseltown politics is essential for contextualizing these pictures.

The Breaking Point is a lesser-known version of Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not, a 1937 novel that was influenced by the writer’s growing involvement in the Popular Front; a cultural movement born in the labor conflicts of the Great Depression and left-wing resistance to European Fascism. The 1950 screen adaptation starred John Garfield, an actor associated with Communist party backed labor and social activist groups going back to his days with the Federal Theater Project and the Actor’s Studio, which he co-founded. As the actor’s political activities began appearing in anti-communist pamphlets and tabloids around the time of the movie’s release, Warner Bros began soft pedeling the film’s marketing campaign. That’s really too bad, as it’s a tense and deeply humanist little crime film, muscularly directed by Michael Curtiz, that significantly advances the two-fisted Warner’s tradition. Garfield’s death of a heart attack two years after the remake’s release is widely believed to have been caused by harassment by the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Try and Get Me! was directed by Cy Endfield, who was also called before congressional investigators on account of his pro communist leanings. Like Garfield, Endfield came from the avant-garde theater, and developed a sense of stagecraft from Orson Welles’ Mercury Theater, which, in its New York days, produced many left-leaning plays like Mark Blitztein’s The Cradle Will Rock. Like Joseph Losey, he decided to leave the U.S. and work abroad rather than name names after this independently produced film’s limited release. In England, he teamed up with actor and labor activist Stanley Baker for a series of working-class crime dramas such as Hell Drivers, as well as the colonialist military epic Zulu. In short, one cannot overlook the context of communist influence in the film industry as these pictures interweave social observations with explosive, hard hitting action.*

Yet these pictures are too diverse in their modernist influences to be read as reductively Marxist. This is completely understandable, as the Communist Party’s cultural front was not as doctrinaire as commonly portrayed in the media. Due to the general pro-worker vibe of the New Deal (best represented by the Wagner Act, which guaranteed laborers the right to collectively bargain, vote for their union representatives, and established the National Labor Relations Board to mediate disputes and elections), the CPUSA spread its influence by assimilating into mainstream liberal institutions. Earl Browder, the Party’s president through most of the 1930s, even went so far as to proclaim that,“Communism is 100% Americanism”. Consequently, members of the group’s Hollywood elite, and those “fellow travelers” who worked on committees advancing labor causes, civil rights, and anti-Fascism, melded Marxism with other strands of progressive thought. The movement’s intellectuals constituted a coalition across a progressive continuum, not an ideological monolith solely dedicated to historical materialism.

Both The Breaking Point and Try and Get Me!, as you point out, argue for sustaining normative standards of masculine comportment through the family. This notion comes from the field of social psychology, which merged Freudian models of personal development with Progressive Era theories linking negative environmental conditions to crime. In both films, the characters succumb to the lure of criminality in the face of economic obstacles. Harry smuggles Chinese nationals across the border from Mexico and later assists in the getaway of gangsters after a race-track robbery. Howard engages in robbery and kidnapping. Both actions lead to fatal results. Both protagonists were not instinctually deviant but were defined by their failure to measure up to normative breadwinner expectations. Both pictures have poignant scenes where they give their precious pocket change to their children so they can enjoy candy or movies, and both characters experience embarrassment when appearing drunk or angry in front of their family. Howard experiences a loss of self-esteem upon having to take his wife to a free clinic in order to deliver his child. Economic conditions are tough for those of limited professional training, but the films never discuss how class might factor in these situations.These are social-problem movies about masculinity in a culture of individual self-actualization where opportunities are unevenly distributed.

These movies also address issues raised by the popular front that gained greater traction as the 1950s progressed. The Breaking Point is surprisingly nuanced in depicting America’s racial social strata, and Try and Get Me! expands its focus from crime to vigilantism, calling to mind an earlier period where lynching and the influence of an unchecked reactionary populist media were rife in American rural life. In some ways the attention paid to these issues (particularly in the latter) doesn’t necessarily commit to the type of social change that one associates with the left. There is, in the Garfield movie, a pronounced anxiety concerning the demarcation of racial and cultural borders, and Endfield’s film distrusts some forms of disruptive collective action as a means to obtain justice. What do you make of this? Do the tropes and practices of Hollywood storytelling dilute, or subvert, the promise of radical action even in movies with presumed radical content?

JB: That’s a great question, and it goes back to what I was saying about Hollywood films and Marxist critique. In The Breaking Point and Try and Get Me!, the radical premise does not translate into radical action. Not to put too fine a point on it, but to show, in both films, families in danger of falling apart due to fathers/husbands unable to be steady providers would expose the myth upon which domestic containment depends: that working hard results in a living wage for all. In particular, The Breaking Point devotes a considerable amount of screen time showing us the time, labor, and money required to keep a fishing boat in working order. And as you point out, Howard’s embarrassment at being unable to provide for his family at the beginning of the film is conveyed at an almost uncomfortable level of pathos. The noir elements, however, in these films create a narrative shift away from their radical premise.

In The Breaking Point, the double-crosses, which, when they cross racial lines, ramp up the tension even further, place Harry in an increasingly unbearable situation as he faces the collapse of his business and his marriage. The threat to his marriage is the sexually-voracious Leona, played with a perpetually-smouldering allure by Patricia Neal. While in a more socially-conservative noir, she would be regarded as a femme fatale, in the morally complex world The Breaking Point constructs she has, overall, a positive influence on Harry. Stephanie Zacharek, in her essay for the 2017 Criterion edition of the film, contends,

In The Breaking Point, the double-crosses, which, when they cross racial lines, ramp up the tension even further, place Harry in an increasingly unbearable situation as he faces the collapse of his business and his marriage. The threat to his marriage is the sexually-voracious Leona, played with a perpetually-smouldering allure by Patricia Neal. While in a more socially-conservative noir, she would be regarded as a femme fatale, in the morally complex world The Breaking Point constructs she has, overall, a positive influence on Harry. Stephanie Zacharek, in her essay for the 2017 Criterion edition of the film, contends,

Leona doesn’t bring about Harry’s downfall. And if she tempts him, she also catches him up in a whirl of healthy erotic energy. ‘A man can be in love with his wife and still want something exciting to happen,’ he tells her at one point, an admission of weakness that tells us how strong he really is.

And we see “how strong he really is,” for, when ruthless gangsters back him into the tightest of corners, he pulls off a hyper-individualistic feat that epitomizes a rugged masculinity forged in acts of wartime heroism. Similar to how Leona’s temptation proves the strength of the love between Harry and his wife, the losses that Harry suffers – the death of his best friend, Wesley, which, then, leaves Wesley’s son fatherless, and the amputation of his own arm – while defeating the gangsters in a climactic shootout add a tragic sheen to his heroic status. As the film thus shows us, a male hero somehow triumphs against all odds, even when the economic system is rigged against him. While Harry gets his wife and children back, the tearing apart of Wesley’s family does sound a note of ambiguity regarding the prospects for the success of a policy of domestic containment.

In Try and Get Me!, the noir aesthetic becomes intertwined with social determinism. Once Howard falls in with Jerry, the die has been cast. As Howard reckons with his fate, the film veers between naturalism and expressionism in a scene at a nightclub – where he and Jerry are trying to lay low with two women who are Jerry’s friends – expressed partly from Howard’s point of view. Howard’s guilt is torturing him, which is depicted in a nightmarish sequence of disorienting camera angles and lighting effects.

At the same time we move inwards, we move outwards, to the perspective of a social observer, a prototypical right-wing newspaper journalist, who’s been riling up his readers by playing on their fears that Jerry and Howard’s local spree is actually part of an incipient crime wave of unthinkable proportions. At this point, it becomes clear that the film is juggling multiple sociological theories about crime, and is unable to find a way to express a coherent message through the characters.

What saves the film from becoming a rote exercise in didacticism (the kind of thing that Mystery Science Theater 3000 delights in mocking) is the tightrope it walks between naturalism and expressionism. Although the journalist, who comes across as less evil than simply too absorbed in the professional mindset of his craft, eventually realizes the error of his ways, it’s too late to turn back the angry crowd. I’d argue that the lynching scene doesn’t work if it’s meant, in a purely naturalistic register, to create sympathy for Howard and Jerry, who are, of course guilty. But it does work if it’s intended, in an expressionistically-intoned version of naturalism, to dramatize the horrific extremes of conspiracy theories when they are amplified through the media.

Earlier this summer, I was watching the Western Noir series on the Criterion Channel, and it occurs to me that the climactic shootout in The Breaking Point and the lethal dose of frontier justice in Try and Get Me! appear as Western-derived tropes. As we’ve been looking at the inability of the noir aesthetic, in these films, to express a sustained social critique (like it does in, say, Force of Evil [1948]), how might we further explore how these films, viewed through the diversity of American Socialist thinking, blur genre distinctions?

SoG: Most viewers would casually classify The Breaking Point and Try and Get Me! as films noir. They come from 1950, have crime as their subject matter, and are shot in high diachromatic contrast with actions blocked in deep focus. But as you suggest, and as many critics point out, film noir is a complicated category that doesn’t follow the rules that we often associate with “classical” genres. Its stories can be set in any particular era or place (unlike the Western); it doesn’t necessarily have distinguishable archetypes, gestures and props, nor a singularly recognizable dramatic structure. Classical genres, in fact, superficially mask their actual thematic narrative structures.

As Will Wright noted back in the 1960s, Westerns repetitively invoked narratives around recurring themes of homesteading, “town taming”, revenge, and professionalism. Only the first constitutes a story type that is essential to a frontier setting. The other thematic patterns are also invoked in genres such as hard-boiled detective and gangster sagas. Thomas Schatz notes that these three genres have protagonists who archetypically embody male alienation from community and family. Characters like Shane and Ethan Edwards defend the viability of prairie-based family and community units but stand apart from them on account of their violent nature. As opposed to having that sense of estrangement come from the character, The Breaking Point and Try and Get Me! convey how existential choices, forced by external circumstances, withdraw their heroes from domestic integration. Domesticity tempers their tendency for socially-disruptive action, but the instability of their family’s middle-class status draws them into the two-fisted world of film noir.

Film genres’ emotional patterns are dramatically orchestrated to heighten the viewer’s feelings of suspense. In film noir, narratives highlight the claustrophobic entrapment of the lead characters by authority figures who set out to punish them for transgressing against social and legal norms. “Noir” Westerns, exemplified by Pursued (1947) and Colorado Territory (1949) invoke this pattern. In the pictures that we are discussing, the authorities represented by the Coast Guard in The Breaking Point and the police and the press in Try and Get Me! survey and constrict the protagonist’s actions in public space as their plans disintegrate. The dramatic action’s faster pace in relationship to the encroaching presence links the characters’ paranoia to the audience’s anxiety invoked by the rapid unfolding of the plot. Ultimately, the injuries inflicted upon the pictures’ anti-heroes release that tension by allowing for the restoration of each film’s social order to its previous state.

In terms of larger artistic movements, films of this nature demonstrate how romanticism, which privileged emotionalism and subjective experience, was reproduced in mass culture in a manner that normalized static social relations. When pressed to explain why these films failed to follow through on a Marxist social critique, I recall the writings of the Frankfurt School of Social Research, whose exiled members congregated in Los Angeles and often hobnobbed with the Hollywood community. Its key members (Siegfried Krackauer, in particular) traced a relationship between “dark” romanticism and a desire for authoritarianism in movies. Max Horkhiemer and Theodore Adorno further argued that mass production facilitated the rapid reproduction of emotional sentiment in a manner that rationalized industrial priorities. Romanticism’s radicalism, as demonstrated in the 19th-Century European and Latin American nationalist revolutions, was diffused as it was assimilated to the instrumentalist logic of industrialism. The drive to increase the rate of production not only universalized its mode, as Marx argued, but leveraged representations of cultural norms to sustain the normality of economic prerogatives.

The interchangeability of genre elements as facilitated by the culture industries’ functionality explains the presence of Western tropes in our films noir. The anxiety provoked by borderlands, marking boundaries between opposing racial and economic interests, is a fundamental element in The Breaking Point. As he loses a charter in Mexico, Harry agrees to “rustle” Chinese laborers into the U.S. The bargain is struck in an exotically seedy Ensenada cantina filled with swarthy men, spitfire female musical performers, and a dissolute colonial criminal entrepreneur donning a soiled white suit. Due to a murder resulting from this indiscretion, the authorities seize Harry’s boat, forcing him to further indemnify himself to the smuggling ring’s lawyer for further “favors”. In the third act, he helps a group of race-track robbers make a getaway so he can turn them in to the police for a “bounty”. The film, in short, deploys frontier iconography to expressionistically depict how the disciplinary forces of civilization, in the form of the law, will close in on the character.

While The Breaking Point’s nods to the Western are largely atmospheric, the allusions of Try and Get Me! are narratively essential. It uses lynching, the epitome of frontier justice, to amplify a tragic conceit that crime, as an act of individual moral forfeit, can escalate to epidemic proportions. Its take on mass vigilantism, as in most Westerns, focuses on how populist violence, once necessitated by the lack of civilizing institutions guaranteeing individual rights, imperils democratic legal principles and institutions. Novelist Joe Pagano based his story on an actual 1937 lynching near San Jose, California, when 10,000 citizens tortured and hung two white men suspected of kidnapping and murdering the son of a well-off community leader. They acted on fears, whipped up in the local media, that the defense’s use of a Leopold and Loeb-like diminished capacity defense might set the accused murderers free. As you point out, the film’s climax works primarily as an expressionistic take on naturalism, as the story’s rhythm is built on an unrelenting escalation of consequences stemming from Howard’s bad decisions. While the movie portrays authority, in the form of the mob, as an evil by relating its terror through the prisoner’s point of view, it doesn’t so much explore the lynching as a social phenomenon but as a plot device designed to heighten the audience’s feeling of suspense.

In short, the interchangeability of genre tropes within formulaic thematic narratives for the purpose of elevating feelings of suspense takes a higher priority over sustained social critique in what we might call topical suspense films. The workings of society, as a subject, is reduced to the perspective of individual self realization. One effect of this, as you noted a while back in your essay on All the King’s Men (1949), is an inherent rejection of the notion that social enlightenment might emerge through a mass assertion of a General Will. Hollywood’s “progressive” attempt to depict working class political culture at the height of the Depression, in films like Black Legion (1937) and Black Fury (1935), demonized operatives, on both the right and left, who mobilized mass protest directed at changing political and economic institutions and norms. The retreat from radical towards moderate to conservative politics is not necessarily complete, as there are often loose ends and residual moments of radicalism at each film’s fringes. John, could you address the ending of The Breaking Point and how it creates a less than full sense of closure?

JB: I’ve been thinking about this question, and I think it comes down to how the film can be viewed as a hard-boiled romance story. While somewhat critical of the fungibility of social values, the film’s worldview, over time, appears constrained by a free-market ideology.

There is, of course, a twist in this romance formula that cranks up the intrigue. The woman, Lucy, is not an outsider, but Harry’s wife, who’s been with him all along. It’s Harry’s stubborn attitude, however, of having to do everything by himself that creates tension in their relationship. Because he’s a flawed good guy, tempted yet not seduced by Leona, his outcome follows a logic favored by noir: fate is determined by character.

But such logic doesn’t at all seem to square with the tragic death of Wesley, who’s in the wrong place at the wrong time. On the boat when the gangsters arrive, Wesley, with an understandable premonition of danger, tries to physically intervene in order to stop Harry from carrying out the plan, and is shot dead by the head gangster. Here fate takes a cruelly unforeseen turn, another noir trope that lends itself to dramatic possibilities.

Not only do these multiple definitions of fate build moral complexity; they challenge a “classical” generic interpretation of the film. In response to your observations about genre, I’d suggest that noir tends to move away from a fixed tonal center. In The Breaking Point, tragic images signal a shift from a naturalist milieu and compel a reassessment, staged in an expressionistic way, of Harry’s actions. Doing everything himself has resulted in victory over the gangsters, but he’s been left critically wounded and stranded at sea, his best friend is dead, and Lucy’s earlier threat, to leave him and take the kids if he went through with the plan, hangs in the air.

“A man alone ain’t got a chance,” he repeats in a state of delirium. Taken directly from Hemingway’s novel (and can be read as the novel’s statement of purpose), these words cue his timely rescue by the Coast Guard and a dramatic reunion with Lucy.

Presumably, with the reward money he’ll receive for killing the gangsters, Harry and his family can buy into the dream of social mobility. They can relocate at a safe distance from the dock-side underworld that had symbolized Harry’s bad conscience fed by wartime trauma. What also, significantly, pulls him away from such a crooked environment is the loss of his arm. Although reluctant, at first, to become differently abled, Harry allows Lucy to talk him into having his arm amputated in order to save his life. In the wrap-up on the film, when it was shown on TCM’s Noir Alley, Eddie Muller, the series host, remarks that “instead of becoming a symbol of emasculation, the loss of his arm is what solidifies his bond with Lucy.”

After the drama subsides, the camera pulls back to briefly take in Leona, who’s seen in the company of a moneyed man. Then in a crane shot, we see the rest of the crowd disperse, leaving Wesley’s son, now fatherless, alone on the dock in the center of the frame. Whether or not he has got a chance is a question left open. Watching the film in 2020, the Black identity of Wesley and his son would become even more of a critical factor in answering such a question.

Although the ending of The Breaking Point carries a powerfully emotional charge, it cannot propose a viable alternative to an economic system where someone must invariably pay – in this case, someone relatively innocent as to the ways of the world – as the cost of doing business. Son of Griff, how might we look at the final act of Try and Get Me! with regards to this cost? Who pays, and how much?

SoG: Before answering this question, It’s also interesting to consider another level of ambiguity regarding Harry’s future, should he 1) recover from his injuries, 2) retain Lucy, and 3) not have his foreknowledge of the robbery exposed by the police. Between criminal escapades, Lucy encourages Harry to take a job as a foreman at her brother’s ranch in Salinas, where he would possibly be supervising the agricultural laborers he helped smuggle into the country. Whatever course he may take, he would still be enmeshed in the economic conditions that resulted in his criminal actions. (I would love a David Thomson’s Suspects hyper-textual link where Harry dukes it out, Spencer Tracy style, with Border Incident’s Pablo Rodriguez).

I think you are referring to a shift in focus midway through Try and Get Me! from Howard’s perspective, whose destiny is pretty much secured by his arrest ¾ of the way through the film, to that of Gil Stanton, a journalist whose writings shape the mode by which the debt Howard owes is collected. Gil doesn’t resemble a typical tabloid hack. He wears a pressed suit whether he is at home or in the office, has an adoring wife, makes a hell of a martini, and entertains prominent intellectual figures wise to conditions that give rise to populist totalitarianism. If Victor and Ilsa Lazlo popped in for a nightcap one wouldn’t be a bit surprised. He embodies trademarks of professional middle-class respectability. The cost, one suspects (as the film doesn’t strongly dramatize it), comes from the burden of self-realization: He has initiated a breakdown of civil institutions that ultimately protect him, and his class, from the threat of populist “mob” justice.

His fate is to internally carry the weight of how his actions have precipitated a social tragedy and violated his commitment to reasonable liberal principles. After the credits roll his project is to therapeutically reconcile the ambitious side of his ego to the larger set of values he professes but betrays through his writing. Here we see the more expansive range of progressive ideas fostered by the Hollywood Left, namely, that personal self-realization might result in social mass actualization. There might also be some self-criticism here: what is the effect of hack writing on the general public?

The privilege of who obtains wisdom through self-reflection, and who does not, is determined by class. Outside of the cinema, race factors in as well. In her study of how racial ideology affected the social treatment of unwed mothers during the Cold War, Rickey Solinger noted that the white middle-class handled single motherhood during the Cold War as a personal, psychological issue. They prescribed therapy in order to integrate pregnant teens back into domestic settings. Social workers handled inner-city single mothers, who were mostly African American, as part of a long-festering sociological crisis stemming from the absence of fathers, a concept that would most famously be presented in Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s controversial report on poverty and single-parent families in the 1960s. Whites got shrinks and Blacks got sociologists, and thus the latter’s fate became enmeshed in the politicization of the welfare state. While Try and Get Me! portrays Gil’s angst in terms of existential turmoil, it extends a sociological gaze over the public sphere of small-town America, depicting how social media, mass fear of crime, and psychoanalytic theories of jurisprudence provoke mass-reactionary violence in the heartland. The film’s expressionist aesthetic underscores a vision that puts white society, rather than just the self, under the lens.

Our earlier discussion of Western motifs comes into play here, subverting postwar notions of the permanence and perfectibility of American social and political society. The Western’s setting and time frame separates the brutalism of the past from the present. Violence on the old frontier regenerates a social contract operating in contemporary times that recognizes individual rights and freedom and discourages iniquity and force. The recognition that extra-legal hangings could kill the innocent (as in The Ox-Bow Incident [1943]) or mask personal hatreds or economic conspiracies (as in Devil’s Doorway [1950] and Johnny Guitar [1954]) prompt new systems of justice achieved through due process and reason. Try and Get Me!, to the contrary, suggests that social insecurity bred from the uncertainty of frontier colonization still resides on American soil. Lynching, the movie asserts, symbolizes the recurring legacy of American violence, and is still a project that socially-progressive ideology needs to address, even though it may never end it.

While commentators often describe the popular culture of the late 1940s and early 50s as politically timid and aesthetically bland, both The Breaking Point and Try and Get Me! invite us, to use your words, to read against the grain. Despite Marxist involvement in these projects, they don’t sustain a fully systematic critique of the Capitalist economy lionized by American politicians. Despite overt persecution, the artists involved in these films engaged in modern psychological and sociological musings from the progressive ends of the political spectrum, and used the instrumental prerogatives of mass storytelling production to subtly subvert standard representations of masculinity and domesticity. To the best of their ability, they provide an entertaining yet critical perspective on the narrative norms of Hollywood, and America, for their time.

* It should also be noted that Try and Get Me!’s screenwriter Jo Pagano and actor Lloyd Bridges, among others in this production, were also investigated by Congress for their political contacts in the 1930s and 40s.