Pre-Introduction Introduction

I’m a fan of Michael Schur.

I feel like I should get that out of the way first. I think the shows he’s created and worked on range from “solidly funny” to “some of the best tv comedy ever produced”. And although they mostly end poorly, that’s hardly unusual for sitcoms.

Likewise, he strikes me as a decent person. Friendly, quick to share credit with his coworkers and employees, intellectually curious, and conscientious in his words and (at least his public) behavior. And Schur’s politics seem genuine. His liberalism seems more aligned with that of actual human beings; The liberal voters who want a fairer, more equitable society and would probably more accurately be considered social democrats, rather than the neoliberal political and media leadership. However, what makes Schur such a fascinating and frustrating figure is how much his shows have epitomized the outlook of that particular liberal media class (most obviously with Parks And Rec, but it’s also there in the copaganda of Brooklyn 99 and the “building a better hell” of The Good Place). There is an undercurrent in Schur’s work of his natural empathy and intelligence wrestling with his desire to follow the rules and support the system. And because his work is often overtly about politics and philosophy, while also struggling not to alienate any viewers who may not share the same ideological or religious views, it ends up being very revealing in a way that shows that were either more or less propagandistic would not be. In order to make his point without relying on potentially alienating political rhetoric, Schur must engage with the subtextual underpinnings of modern American liberalism, and he’s doing so from the perspective of a believer but not a zealot.

In How To Be Perfect, Schur is giving us the clearest look yet into his ideology. Stripping away all the narrative, tonal, and budgetary limitations of a sitcom, we are getting Schur’s thoughts on how we ought to live, directly from the man himself. In the version I listened to, it was even read by the man himself, with most of the principal actors from The Good Place making auditory cameos. What was intended to be a simple, straightforward, and lightly humorous introduction to moral philosophy, is instead is a tedious, rambling, and condescending window into Michael Schur. And it is as revealing, and fascinating, and frustrating as the best of the man’s work.

Let’s get into it.

Tens of thousands of years ago, after primitive humans had finished the basic work of evolving and inventing fire and fighting off tigers and stuff, some group of them began to talk about morality. They devoted part of their precious time and energy to thinking about why people do things, and tried to figure out ways for them to do those things better, more justly, and more fairly. Before those people died, the things they said were picked up and discussed by other people, and then by other people, and so on and so on all the way to this very moment—which means that for the last few dozen millennia, people the world over have been having one very long unbroken conversation about ethics.

Most of the people who’ve devoted their lives to that conversation didn’t do it for money, or fame, or glory—academia (and more specifically, philosophy) is not the best route, if that’s what you’re after. They just did it because they believed that morality matters. That the basic questions of how we should behave on earth are worth talking about, in order to discover and describe a better path for all of us. This book is dedicated, with my extreme gratitude, to all those who have engaged in that remarkable and deeply human conversation.

It’s also dedicated to J.J., William, and Ivy, who matter the most, to me.

Already I take exception. I wouldn’t describe the evolution of moral philosophy as “unbroken” and I think Schur is projecting a lot onto the motivations of a “few dozen millennia” worth of philosophers. We also have an “and stuff” in the very first sentence of the introduction. One should not write a book of philosophy in the same voice as one writes sitcom dialogue. Surely that must be a virtue.

Schur follows this introduction with a warning and an apology that there will be swears in this book.

Today, you’ve decided to be a good person.

Holy Shit, it’s written in second person. Schur describes Your sudden desire to be a good person and the actions You take to pursue this. You recycle some trash, buy organic eggs and a vegan beef substitute, go jogging, watch a documentary, watch the gosh dang news, and help an old lady cross the street.

I notice these examples mostly concern Your consumption habits, with only helping the little old lady, having any kind of direct impact on another person. Schur is not convinced either.

You feel like you did some good stuff, but then again you also felt like you could pull off wearing a zebra-print fedora to your office holiday party last year, and we all know how that turned out.

Is a zebra-print fedora supposed to be relatable? I feel like this scenario would work better if I were watching a sitcom character perform it, rather than being told I’ve been doing and feeling all these things.

So now imagine that you can call on some kind of Universe Goodness Accountant to give you an omniscient, mathematical report on how well you did. After she crunches the numbers on your day of good deeds and the receipt unspools from her Definitive Goodness Calculator, she gives you some bad news.

I’m trying not to quote this whole book, but what can I even say about this. Schur is making so many leaps here. It looks like The Good Place‘s point system is not just a plot device, but going to be underpinning our entire discussion of ethics. Anyway, turns out Your pitiful attempts to do good totally backfired, idiot. This is because almost every interaction you have under capitalism is built on the suffering and exploitation of others (my phrasing) and because that old lady was a “Secret Nazi” “on her way to buy more Nazi stuff” (Schur’s phrasing).

Schur claims that ethical questions are more difficult today because of how complicated the modern world has become.

Did you know that during the Great Depression it was common for people to sell their children because they had no means to support them? Imagine having to make that choice. Figuring out exactly what you are capable of providing. Choosing which child to abandon. Do you give up several, so that they’ll at least have eachother, or do you try to protect as many as possible, letting only the oldest or strongest take the brunt of it? How do you weigh the damage of poverty against the emotional damage you’re inflicting? How many missed meals is a parent worth? That is a more ethically complex question than whether or not watching Lethal Weapon makes you a bad person.

[Today] we have to think about how we can be good not, you know, once a month, but literally all the time.

Friends, I was worried there wouldn’t be enough for an essay.

****

Schur now begins yet another introduction, telling us why he’s writing this book. This really could have used an editor.

if we can get past the fact that a lot of those philosophers wrote infuriatingly dense prose that gives you an instant tension headache

Don’t tell me how much trouble you have understanding philosophy in your book that’s supposed to be teaching me philosophy. Also, I’m somewhere in the middle of the third introduction here, and I feel like it wouldn’t kill Schur’s prose to gain a little density.

You don’t need to apply for a license to be ethical, or pay an annual fee to make good decisions.

Holy Shit, dude. Webster defines ‘good’ as…

My God, there’s another introduction!

This introduction is a series of weirdly passive aggressive questions asking Schur why he’s writing the book and making what seem like pretty fair criticisms of what we’re about to read. Schur continues to tell us that we’re idiots and reading actual philosophy would give us all tension headaches. He also assures us that “This book is in no way meant to make you feel bad about whatever dumb stuff you’ve done in your life.” Ah great, an introduction to ethics that won’t challenge my behavior. I’m sure this will be edifying. Schur also lists several philosophers he “shied away from” including David Hume, so he’s also going to be wrong about a bunch of stuff.

Ok, now we’re finally to the point where Schur is no longer introducing the book, instead introducing the idea of moral philosophy. He tells us that it’s important to understand the ethical underpinning of obvious choices (“should I punch my friend in the face for no reason”) so that we can then apply that code to more complex situations. And then complains some more about philosophy.

Philosophers describe “good and bad” in a bunch of different ways, and we’ll touch on many of them in this book.

Is this book meant for people who were too dumb to watch the sitcom? I appreciate the effort to strip away the jargon, but there’s a reason why philosophical texts are so precise in their terminology. Clarity is more important than simplicity.

One philosopher even suggests that goodness comes from being as selfish as we possibly can and caring only about ourselves. (Really. She says that.)

Great, no David Hume but we’ve got room Ayn Rand.

Schur is very focused on dividing people between “good people” and “bad people”. This strikes me as a very childish way of looking at morality. Punching your friend in the face is wrong because it hurts your friend, not because it’s something bad people do.

I’m really surprised by how intensely unfunny this writing is. I’m a fan of Schur’s work, but this is embarrassing. Thomas Ligotti’s book about how we should all just kill ourselves was legitimately a funnier piece of writing.

***

The First Glob Of Ethical Philosophy

We are now discussing Aristotle and virtue ethics, which means we’ve come to a sentence that many of you may recognize.

Some of the thinkers we’ll meet later have theories that can be decently presented in a few sentences; Aristotle’s ethics is more of a local train, making many stops. But it’s an enjoyable ride!

Just complete nonsense. Embarrassing piece of writing. Do you want to know what comes after that sentence? I’ll tell you anyway.

When do we arrive at good person station?

Good. Person. Station. This man has been nominated for 20 Emmys. Aristotle is going to be interpreted for us by a man who is concerned about when he will arrive at good person station.

Schur tells us that from a young age he was obsessive about following rules, pretty much regardless of their utility, and that he never outgrew this. It’s not a surprising revelation, and it’s the reason why his entire approach to ethics is filtered through this ‘how to get an A’ framework, rather than being rooted in empathy and in understanding the consequences of his actions.

***

The Trolley Problem

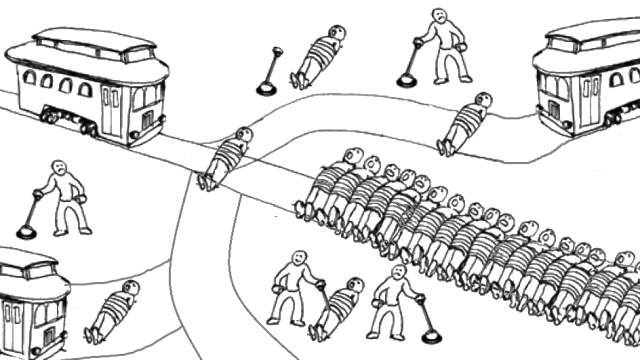

Schur lays out first the original trolley problem: There’s a runaway train on course to kill five people and you have the option of diverting it to a different track where it will only kill one person. Is it morally permissible to actively kill one innocent person in order to save five?

Schur then includes some of the common variations of the question. What if instead of passively flipping a switch, you instead stop the train by throwing a morbidly obese man onto the tracks? It’s the same consequence, one life for five, but requires a more violent means of achieving. If there are five patients in a hospital and each needs a different organ, is it morally permissible to murder a healthy man and divy up his organs between the dying? Once again you are trading one life for five.

Schur brushes past these, instinctively rejecting the messier methods. But there is an answer here, of sorts. The difference between the easy question and the hard question is certainty. In the initial trolley problem I can be reasonably sure that one of two things will happen, I will throw the switch and one person will die or I will refuse to throw the switch and kill five people instead. However, in the case of the fat man, there are a great many possible outcomes of my actions. It’s possible that throwing the man onto the tracks will stop the train, but it’s also possible that the train will barrel right through him killing all six people, or that the train will derail killing the passengers, or I’ll miss the track entirely, injuring the man for no reason, or worst of all, perhaps he will throw me onto the track. To make this decision I need to weigh not only my desired outcome, but every likely or unlikely outcome of my actions. And if I’m not able to be confident that my actions will produce a good result, I can’t reasonably commit to them – especially at the cost of someone else’s life.

Likewise, the good doctor has a more complicated choice to make than originally presented. Obviously, there is a risk that any or all of his patients will die, regardless of the care he provides. But there is also the choice of who to take the organs from. He could kill a healthy man to save five, or he could kill one of his dying patients to save the other four. That doesn’t sound quite as morally perverse. In fact you may even get one of the patients to volunteer, or for the five to agree to draw lots. There’s a Mark Twain story where a train is standard in a blizzard and the inhabitants have to resort to cannibalism to survive and they select which of them will provide the meal democratically, dutifully following Robert’s Rules Of Orders. That story is a lot shorter than this book, and probably this article as well.

Schur does mention some of these principles offhandedly, while describing the work of Jeremy Bentham, but he never applies them to his ethical questions. In fact, he outright mocks them.

How can we calculate the “fecundity” of loaning a coworker twenty bucks, or the “purity” of eating a fried turkey leg at a state fair?

These are rhetorical questions and we are not meant to answer, ‘loaning a coworker $20 most likely has low fecundity (that is, only minor lasting effects) and eating a turkey leg at the State Fair is suitably pure (it causes very little suffering to others)’. No, caring about the “results or consequences of our actions” is clearly absurd.

The utilitarian cruise ship has no first class section reserved for the wealthiest passengers—everyone’s room is the same size, and everyone eats from the same buffet….

Utilitarianism Is Not “the Answer”

Schur now lays out the case for why our ethics aren’t connected to the consequences of our actions.

That’s what a lot of the problems with consequentialism boil down to, really—sometimes it simply feels like the conclusion we come to, when we tally up the total “pleasure” and “pain” resulting from a decision, just can’t be right.

This is hardly a persuasive argument. The whole point of having a system of ethics is to direct you to ethical behavior even when it’s not intuitive. Furthermore, who’s to say your conclusions, your moral arithmetic, is correct?

Bentham’s greatest happiness principle also suggests that if a pig has enough pig slop and mud to roll around in, the pig is “happier” (and thus, more “successful” in its life) than, say, Socrates… Any ethical theory that suggests a muddy pig had a happier and better life than one of humanity’s greatest thinkers is in trouble right off the bat, probably.

This was a charge leveled against utilitarianism in Bentham’s own time, and the response from utilitarians was, to paraphrase, “why do you think pigs are happier than people?” However, taking the charge seriously, why is it unethical to believe an animal might experience more happiness than a great thinker? We do not get to choose whether we want to be born as pigs or as Socrates. Nor is utilitarianism about maximizing our own personal happiness, but about the total happiness of all people. It’s hardly heretical to suggest that great moral leaders may lead somewhat miserable or tragic lives.

Schur next includes a thought experiment about an electrician who is being electrocuted during the World Cup and to save him, the feed to the game needs to be shut off. He believes, for some reason, that utilitarian ethics would weigh the collective displeasure of missing the game higher than the suffering of the electrician. Schur admits that actual utilitarians reject his conclusion – living in a society that will torture someone in order to keep a tv show from being interrupted causes suffering*. But Schur treats this as essentially cheating. This whole line of argument basically boils down to “the values I want to hold aren’t the values I actually hold when applied to actual situations or when I’m asked to defend or clarify them in any way”.

And of course, people do actually suffer and die to bring us various luxuries. Every single industry, nearly every facet of society, costs lives to keep running. Utilitarianism gives us a framework to discuss this cost, to decide what is worth it and what is unnecessarily cruel.

* Despite Schur’s tendency to boil down all of his terminology to “good” “bad” and “stuff”, a big part of his problem here is how narrowly he’s defining terms like “happiness” – even contrasting it against “sadness” at a few points. This is why actual books of philosophy spend hundreds of pages defining even the simplest terms. Happiness is nearly as broadly defined as good, and contains all sorts of other emotions like satisfaction, fulfillment, peace, liberty, and on and on. Likewise suffering is more than just physical pain or even emotional pain. The fact that all these different states of being are nebulously and subjectively defined is a problem for utilitarianism, but it’s just as much a problem for all moral philosophy. Human experience involves a lot of subjectivity.

Schur now very briefly discusses the problem of uncertainty in utilitarian ethics, however he doesn’t take the obvious next step – we should weigh risk into our decision making process – and instead shuffles along to tell us that some British aristocrats didn’t like utilitarianism and to whine about Hawaiian pizza. Again and again Schur’s ethics seem centered around what kind of food to buy.

Schur’s next attack on utilitarianism involves a man visiting a South American Banana Republic that his friend is ruling over with an iron fist. The sheriff here regularly murders a dozen natives at random inorder to sow fear and maintain control. However this week he offers his friend a choice, our hero can shoot one native himself and that will serve in place of the larger massacre. So what’s your answer to that ethical dilemma?

My answer is that the man has a moral duty to murder the sheriff and liberate the village. Schur says he should let the sheriff kill a dozen people. Have we arrived at good person station yet?

***

What Are The Rules?

We now move on to Kant. Kant was an incredibly influential philosopher. The only drawback to reading Kant is that he was wrong about everything. Kant wanted to create a secular system of ethics, derived purely from reason, that was more or less identical to the religious codes he was raised with. He believed these ethics could be boiled down to a list of rules that one should obey in any circumstance, regardless of the consequences. For example, if your moral code says “don’t lie” you shouldn’t lie even to save someone’s life. This is where the modern term “kunt” comes from.

Kant’s test for his perfectly rational code of ethics was the idea that you should only do something if you would want everyone else in the world to behave the same way. This is obvious nonsense. I might decide to buy a pet beagle. If everyone on Earth bought a pet beagle that would be too many beagles. But everyone on Earth isn’t going to buy a pet beagle. And this silliness extends even to things we might consider moral decisions. If everyone on Earth drove 20 mph over the speed limit that would actually be fine, but if I drive 20 mph over the speed limit and nobody else does, then I’m putting people in hazard.

Even under the best circumstances, Kant is mostly a waste of time. This section is long, and Schur mangles Kant’s ideas only slightly less than I have. I imagine that Kant appeals to Schur because his ethics are the easiest to turn into a report card.

Next we discuss T M Scanlon’s theory of contractualism.

Her first recommendation was that I read a book called What We Owe to Each Other by T. M. Scanlon. So I did. Well, more accurately, I read the first ninety pages, got lost, put it down, picked it back up a month later, got lost again, tried one more time, gave up, and haven’t looked at it since. But I feel like I got the gist.

Schur’s description of Scanlon’s philosophy is vague. The idea is that you ought to follow any moral maxum that no reasonable person could object to. “Reasonable” here is doing an awful lot of work, and frankly I don’t see how this is significantly different than saying “you should do what you feel is right”, but I imagine I would feel differently had Schur actually finished reading that book. At least we’ve reintroduced the idea of “each other”

Next Schur discusses the African concept of “ubuntu”, which is basically a set of social virtues centered around community.

“A person is a person through other people.”

Schur also drops this line

Mandela doesn’t elaborate on what he means here. I choose to see “enabling the community to improve” as a nonmaterial kind of thing.

Doubtless.

***

For the first year-plus of the Covid-19 outbreak, there was one persistent and harmful issue: No one wanted to wear masks.

The ideology that has guided American policy for at least as long as I’ve been alive is this: every quality of a community is a direct byproduct of the individual choices of people within that community, and nothing else. If the crime rate is rising, just say no. If manufacturing is disappearing, buy American. If we are headed for catastrophic climate change, buy new lightbulbs, turn down your thermostat, and recycle. These are not systemic problems that require systemic action to address, they are issues of Personal Responsibility.

America’s failure to properly address Covid was a failure of the government. While you ought to wear a mask, just like you ought not smoke crack, the hyper focus on this issue is a way of deflecting blame away from the powerful and onto groups that are already hated. If Micheal Schur had not rejected a moral philosophy built on examining the consequences of your actions in favor of one about following the rules and being a good person, he would likely focus his anger on the people who had the power to meaningfully affect the course of history.

Every time I see a video where someone screams that wearing a mask in this Taco Bell is a form of oppression, my first thought is: “You’re being unreasonable, and I reject your rule.”

This is exactly what I’m talking about. I’ve seen these videos too, and they are almost always about someone who is 1) impoverished and 2) mentally ill. This isn’t because poor people are less likely to wear masks, but because this sort of media plays off your bigotries in order to shift blame away from the powerful and onto marginalized communities.

***

Here’s an interesting passage:

Scanlon’s book may be a slog, but his theory is not—it’s elegant and simple. In fact, the theory is so simple that Scanlon told me, when I met him,* that his mentor Derek Parfit didn’t find it very convincing. Parfit, perhaps the most important philosopher of the last fifty years, had been badgering Scanlon to write a book. When Scanlon finally showed him his initial writings on contractualism, Parfit responded, “Tim, this is not a moral theory. It’s just a description of your personality.” (Philosophers can be jerks)*

{Note from [Philosophy Consultant Todd May]: Parfit was an objectivist about morality: he believed there is an objective right or wrong that doesn’t depend on our reactions to things. Scanlon, as a contractualist, believes that rightness or wrongness is rooted in our (reasonable) judgments. So from Parfit’s point of view, Scanlon is rooting morality in something too subjective.}

But I disagree—I find contractualism to be a reliable ethical guide when I’m weighing my decisions and my responses to other people’s.

I’m inclined to agree with Parfit here. Perhaps more to the point, I wish I were reading an introduction to moral philosophy written by Todd May, rather than Todd May’s buddy.

***

I have reached the end of the first section of the book, and also reached the point where my criticisms start to become repetitive. Schur’s writing remains unwieldy, long winded, and infuriatingly unfunny. Every joke takes three or four sentences to deliver, and every significant line is sandwiched between two or three jokes. His language remains squishy and imprecise, his tone condescending, and his assumptions about our instinctive sense of right and wrong, baffling. He continues to focus on “good” and “bad” people as two perfectly distinct categories rather than a spectrum, let alone seeing people as containing both good and bad qualities and capable of both good and bad behaviors depending on their own unique makeup and the circumstances of their decisions. And he keeps complaining that Utilitarians expect him to actually do things to better the lives of other people. I mean, a Utilitarian might argue that you should sell your possessions and give the money to the poor. Can you even imagine???

Applying Theory

As the trolley starts to move, a woman named Deb comes running up and jumps onto the outside of the trolley, hanging on to a pole and snagging a free ride. She didn’t pay her fare, but she’s also not taking up any space that could be used by someone who did. Is she doing anything wrong?

Instinctively, we think: Of course she is.

“We”. Schur also keeps talking about jaywalking as a moral transgression. Jaywalking!

Schur spends more time complaining about people who didn’t wear masks during Covid, and then talks about Bill Gates and the amount of money he’s given to charitable causes. Bill Gates is directly responsible for the Covid vaccine being patented, which has prevented poorer countries from producing and distributing vaccines. It’s also worth noting that in the time since Gates went on a media tour promising to give away all his money, his net worth has doubled.

Schur’s focus in these chapters is on very minor moral questions that are either plainly obvious or entirely irrelevant. Should you jaywalk, should you return the shopping cart at the grocery store, should you exercise the absolute bare minimum of civic duty during a pandemic, should you use a bank owned by a bad capitalist or find one owned by a good capitalist, which car should you drive, and so on and so on. This is because his ethics are based on following the rules and ignoring the consequences of his actions whenever those consequences are inconvenient. And he keeps jumping back and forth between portraying these essentially meaningless decisions as hugely important, and portraying people who discuss the consequences of those decisions as being needlessly hectoring.

This ethical dilemma feels unique to our age: When information is so readily available, how do we escape the guilt (or shame) that comes from learning about our unintentionally bad decisions?

A lot to unpack here. First, how broadly are you defining “age”? Commerce has been around for a long time, and every community has had to balance their material needs and desires against the broader ethical implications of what they are doing and who they are doing it with. Is it ethical to trade with Sparta? What’s unique about Schur’s position is that he has the freedom and privilege to actually engage with these questions. A slave cannot boycott the plantation. But Schur isn’t really asking about the ethics of his consumption here. His “dilemma” is how do we escape the guilt that comes from learning about our bad decisions? The unique problem of our age is not that the effects of our actions are too wide ranging, too rooted in an inherently corrupt and destructive system, for us to make non-harmful choices, it’s that the information age allows us to learn about the effects of our choices and that makes us feel bad.

One of the examples Schur uses is that when he moved to LA he bought a car that he liked, but got poor gas mileage. So he upgraded to a Prius, and then found out that the Prius was actually worse for the environment. (Schur says this is because of the difficulty of disposing of the batteries – definitely a serious issue, but as I understand it, the Prius, particularly early on, was unusually dependent on parts assembled in several factories spread around the world. The fuel used to ship parts from say, Taiwan to Canada to Mexico, far exceeded the gasoline a single driver would burn in their entire life, even with a gas guzzler. Global Warming is not the result of consumers making poor choices, it’s the result of global industry).

I wanted to avoid the hypocrisy of driving a car that got bad gas mileage while calling for other people to curb their fossil fuel use… hypocrisy stinks. It’s one of the most infuriating traits we can display…. there’s also a difference between my original hypocrisy (driving a car I knew was bad for the environment) and my accidental hypocrisy.

This is where a system of ethics that is unconcerned with consequences brings you. Schur’s Prius was manufactured whether Schur bought it or not, and the difference in CO2 released over a decade of driving a Prius or a Hummer had an infinitesimally small effect on the climate. But Schur is concerned about being a Good Person™ and that means following the rules, and saying you follow the rules when you don’t really is the worst kind of person. It’s all very juvenile. We are all hypocrites. We ought to be hypocrites. We should have moral values that are beyond what we are actually capable of achieving, values that push us to be better people rather than reassure us that we are already perfect.

***

Schur mentions Bill Gates’s Epstein connections. Maybe there’s hope for him yet.

It’s hard enough to figure out what we’re supposed to do all the time—now we have to be responsible for what we like?

Maybe not.

***

Back To Utilitarianism

If your ethical theory needs to explain why it actually doesn’t give the green light to oppression as it appears to, there might be something big-picture wrong with your ethical theory.

What does Schur think an ethical theory is? If your ethical theory can’t explain why oppression is wrong, then it supports oppression.

This is more of Schur’s discussion of utilitarianism, and it’s more of Schur making bizarre leaps of logic, quoting foundational utilitarians who explicitly argue why Schur’s assumptions are wrong, and then treating that as utilitarians cheating.

Schur is discussing utilitarianism primarily through the lens of two philosophers; Jeremy Bentham, considered the founder of utilitarianism, and his student, John Stuart Mill. Bentham completed his first book in 1780. He was a political radical who advocated individual and economic freedoms, the separation of church and state, freedom of expression, equal rights for women, the right to divorce, the decriminalizing of homosexual acts, and the abolition of slavery, capital punishment and physical punishment, including that of children. The aristocracy largely rejected Bentham’s philosophy which was based on the idea that everyone, including women, slaves, and criminals, had equal moral worth; preferring instead ethical systems based on authority, whether divine, legal, or in Kant’s case “rational”. Kant believed it was wrong for a starving child to steal bread from the king. Utilitarianism argues it is morally acceptable to eat the king, so long as you fed more people than you killed.

Schur ignores the social context of the development of these moral theories, and then takes criticisms leveled at them at face value. He argues that utilitarianism allows for oppression of minorities, so long as a greater number of people benefit than suffer. However, even in passages that Schur himself quotes, utilitarians argue against oppression, firstly, on the grounds that not all suffering is equal and the great suffering of the oppressed outweighs the minor benefits granted to the upper classes, and secondly, that living under an unjust society is itself a cause of suffering, even to those who materially benefit. These attacks don’t make sense when Schur borrows them because they were not formulated to be attacks against “tyranny” but against democracy. The masses might do things that benefit the largest number of people at the expense of the much smaller ruling class. “Yes,” the utilitarian says, “they might.”

Likewise, Schur is very literal with how he defines “happiness” and “pain”. However, utilitarians were not this narrow in their thought. Bentham described utilitarianism as an attempt to maximize utility, which he described as “that property in any object, whereby it tends to produce benefit, advantage, pleasure, good, or happiness…[or] to prevent the happening of mischief, pain, evil, or unhappiness to the party whose interest is considered.” Pain and pleasure, yes, but also good and evil. Now these terms are all subjective, which does cause problems for utilitarians, although not unique problems. One could, theoretically, meet a utilitarian who argues that the pleasure of owning a slave outweighs the suffering and evil of being held in slavery. But that would not be a valid argument, and we would not need to take it seriously.

Meanwhile, we can justify nearly anything through Kant’s categorical imperatives. “Women should be subservient to men” is universalizable. “Homosexuality is immoral because if everyone was gay, we would stop producing children and the species would go extinct”. It’s not just that Kant’s ethics aren’t based on anything concrete, it’s that they require us to actively ignore reality.

Another issue here is that Schur is using the word “oppression” in a totally different way than I am, a way almost completely detached from material conditions. It’s true that a utilitarian will not really care if you eat at Chick-fil-a or watch the Washington Redskins (now the Washington Commies). There is a criticism of utilitarianism here that Schur is dancing around but will never find; and it’s that utilitarianism is a very individualized system of ethics that doesn’t really handle collective action well. Utilitarianism can tell you how to behave if you are the king, but if you’re an ordinary voter with a statistically meaningless amount of influence over your government, utilitarianism doesn’t really care what you do with that influence. There are times when there are large scale social movements, and it is morally correct to engage in those movements, even if your individual actions will have almost no discernible effect on the outcome.

***

But there’s one essential aspect of the human condition that none of them really deals with: context. Few of these philosophies grapple with the plain fact that moral choices are a lot harder for some of us than they are for others, depending on our circumstances.

Utilitarianism does, but you rejected it for saying you should give your money away.

***

Credit Where Due

[John Scalzi’s blog post titled “Straight White Male: The Lowest Difficulty Setting There Is.”] is focused on race and gender, not class, but I feel like you can apply his metaphor to any class structure as well;

Hey, congratulations. Schur also takes some time to criticize the idea of meritocracy. He does it through a slightly patronizing lens (“merit is gained through the opportunities in your life, so marginalized people shouldn’t be punished for their relative lack of merit” rather than “meritocracy is made up, class relations reproduce themselves regardless of merit”) But still, good on him.

Some years ago, a social scientist named Robert Frank was playing tennis with a friend and had a massive heart attack. His friend dialed 911, and the dispatcher called for an ambulance. Emergency vehicles were usually sent from a location miles away and would’ve taken thirty to forty minutes to get to the tennis courts, but as it happened, two ambulances had just reported to the scenes of two different car accidents only a minute from where Frank was lying motionless. One of those ambulances was able to peel away, get to Frank immediately, and save his life. Frank later learned he had suffered from “sudden cardiac death”—a pretty goddamn intense-sounding medical condition that is 98 percent fatal, and the few who do survive it often have intense and lasting side effects, which he did not.

When Frank woke up and learned what had happened, he had a lovely reaction: From that moment on, he thought, everything that happened in his life was due directly to good luck. Without the random good fortune of the nearby ambulance he would’ve had no more moments of any kind, which means that everything he experienced afterward was fruit from that lucky tree. That realization led him to hypothesize that people generally underestimate the role that luck has played in their lives. “Why do so many of us downplay luck in the face of compelling evidence of its importance?” he asks. “The tendency may owe in part to the fact that by emphasizing talent and hard work to the exclusion of other factors, successful people reinforce their claim to the money they’ve earned.” In other words, people who achieve (or inherit) a high level of wealth and success are invested in the idea that they earned it.

Well look, there you go. This is why Schur remains such an interesting and frustrating figure. This book is not some self help cash grab, nor is it some moralistic propaganda piece. It is also not phoned in – well, not entirely. While the book lacks structure and feels very much like a first draft, it does seem like something Schur put a lot of time and effort into. And moments like this it seems like Schur really is about to get it, and then he’ll disappear into some tangent about the ethics of listening to Micheal Jackson’s music or ordering pineapple on a pizza.

No one on earth would say Bill Gates doesn’t deserve what he has.

No one on earth.

***

After this Schur spends about an hour talking about Twitter nonsense, and then another hour with a letter to his kids. I feel like using your kids this way is unethical.

***

Conclusions

What’s fascinating about Schur is that he does genuinely seem to be trying to be a good person, and to figure out what that means. He wants to live in a fairer, gentler, more equitable world and he’s internalized ‘personal responsibility’ ethics so much, that he feels genuine anguish about his failure to bring about this world through his consumption habits. He keeps walking up to these ideas; “I don’t feel like a bad person, but my actions cause harm” “morality must be acted on collectively in order to be effective” “it seems impossible to live ethically in this political/economic system” “people constantly act in an irrational and destructive way, and even I value minor luxuries over the lives of strangers” “our lot in life is almost completely determined by luck”. But he never takes the next step, and he never ties these ideas together into a coherent philosophy.

As a book, though, this is pretty awful. You would get more from watching a couple ten minute explainers on YouTube about Kant, Aristotle, and Utilitarianism than sitting through the nine hours of book here. Schur simplifies his subject, but then adds so much fluff and filler, that we might as well have read the real thing. And every time he nears an interesting question, a place where his philosophy has challenged him to explain something that feels wrong, he backs away. Which is why he ultimately settles on a code of ethics that is basically “do what seems agreeable”.

A better formation for this book would have been either Schur conducting a conversation with one of his philosopher friends, or Schur taking us through a series of ethical thought experiments, which is generally where his writing is the most focused and where he has the advantage of discussing how actual philosophers engaged with these questions instead of having to formulate his own answers. Instead what we get is disorganized, long winded, shallow, and condescending.