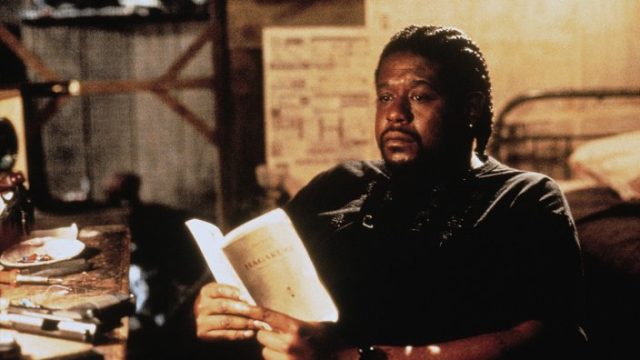

Obviously I read this because of Ghost Dog: The Way Of The Samurai. I was fascinated to see that Nitobe wrote it after the age of the samurai had ended, having never fought in a battle himself. You’d think that would make me less likely to read it – it conjures up images of a Japanese pre-industrial incel moaning about how we do not live in an age of chivalry – but in fact, the exact opposite was true. It helps that I heard Forest Whitaker read interesting extracts from it, of course, but I wondered if there would be something helpful in the idea of someone identifying with samurai values but living in a non-samurai time. Everyone mistakenly thinks of cities as an aberrant feature of human existence; small town folk and hippies think of themselves as closer to what human beings are supposed to be like while hipsters and wannabe intellectuals think of themselves as more enlightened and evolved people; sometimes hipsters and artists and intellectuals whatever have the anxiety David Hepworth identified, in which secretly we (as in a specific group I identify with) feel deep down that the small town folk are right and we’re doing something we’re not supposed to. Based on the limited extracts present in Ghost Dog, I wondered if Nitobe had managed to square that anxiety.

The answer is yes, with the proviso that he doesn’t seem to realise that’s what he’s done and I’m doing a mixture of selectively choosing passages that mean something to me and reading things into the text that I don’t think were intended. In this case, I actually am following the lead of the book a bit – the edition I have comes with an introduction by translator William Scott Wilson, who observes that much of the book’s philosophy is contradictory, partly as a result of the book being a lifelong compilation of records of things Nitobe said to his pupils and friends (which effectively makes it a centuries-old “Shit My Master Says” Twitter feed) as opposed to a consistent and rigorously worked out philosophy. If he contradicted himself, it’s because he forgot what he said earlier, changed his mind, or simply was in one mood one day as opposed to another. The two big recurring themes of the book are the (literally) suicidal chasing of honour and the preservation of face.

I found the former extremely resonant to my life and general view of things; over and over, Nitobe counsels that you don’t just do things that are risky, you actively charge into death with full-throated enthusiasm and understanding. So many of his stories are about people who cut their throats, shoved swords into their bellies, and picked impossible fights fully in the face of all self-preservation and he describes them all with glowing approval. One of the things about being a city mouse and an enthusiastic intellectual or artist is how the stuff you care about is not a matter of life and death – nobody starved to death without a television show – but the combination of genuine belief in the necessity of doing what you do and the anxious hunter/gatherer part of your brain looking for tigers around every corner creates a perfect storm of neuroses. You know that nobody is going to die if you go on stage and completely bomb, but your mind thrives on surviving doomsday scenarios even if it has to exaggerate minor issues to get that sense of survival.

Nitobe’s advice to not just court but embrace death makes a lot of sense when you see it as ego death – something you can survive and learn from. The thing about ownage is that if you survive it, you learn from it, and social ownage by definition does not kill anyone (I have learned not to pick fights with people I don’t want to see get smarter as a result). If you’re already dead, you can die a thousand times and learn from each iteration (“A real man does not think of victory or defeat. He plunges recklessly towards an irrational death.”). A practical example of this is, say, doing a comedy routine and not just allowing but embracing bombing on stage.

It’s the stuff about saving face that doesn’t resonate with me. Nitobe also, basically, pisses and moans for pages with the intent of shaming the listener (as well as society at large) into following what he sees as the correct behaviour. If this has a purpose to me, it’s in clarifying what I respond to elsewhere in the book – much of the world occupied by intellectuals and artists is driven by face – both shame and pride doled out as reward and punishment. Someone capable of charging into situations embracing the shame of others and rejecting the pride they offer whilst able to recognise the power these feelings hold over others (as well being able to dispassionately recognise the practical utility of one’s face) would presumably be the most powerful person in any room.