U2 were aware of their opportunity. The Unforgettable Fire was a test into different production and writing styles, and their Live Aid performance let them both have the world stage a mosey around with names ranging from Van Morrison to the Rolling Stones. Talks about their blues influences made Bono – a man who didn’t really play instruments – feel embarrassed, and in reaction to both those influences and his time around America the band came together to write an album steeped in Americana.

Knowing that now, the influences became much more noticeable to me than on other listens. And that in return made listening to the deeper cuts on this record even more interesting. Because The Joshua Tree suffers in some ways from a double edged sword, in that the first side is of such hit-making quality from the gate that some people could just listen to the first side and miss out on the band, Eno and Lanois’s experimentations. But the sheer familiarity with those hits made this full album experience almost feel like a renewed one. The Joshua Tree, in spite of somewhat shooting its load early on, is a triumph in triumphant music, one whose songs flow from bright to sombre in a way that feels complete in spite of that lop-sidedness.

In the grand tradition of U2 albums beginning incredibly strong, The Joshua Tree is arguably the strongest with the all-time classic “Where the Street’s Have No Name.” (“Beautiful Day” and “Sunday Bloody Sunday” being the main competitors) It’s all in that build up, the two minutes wherein each instrument introduces itself: the lush, silky synths playing like an organ; The Edge’s guitar fading in and speeding through the landscape, Mullen and Clayton bringing in the rhythm with rolling bass and drums, and finally Bono expanding on the sketch ideas from the previous album with descriptions of walls torn down and light upon face that ranges from feeling like breaking out of a dead-end town to even being about heaven. It truly reaches the “cinematic” feel the band were aiming for.

The next song maintains the unbelievable quality with “Still Having Found What I’m Looking For.” With an intro bassline that sounds like the notes are slapping against the broken walls of the previous track, there undeniable gospel influence in the chorus as the song pertains to subjects of self-discovery, and maybe less optimistically the inability to achieve full connection (“we’re one, but we’re not the same” as Bono would go on later to say).

“With or Without You” – lead single and probably the band’s most popular song – is the testament to the power of musical simplicity. The trusty four chords of pop, no frills percussion, guitars more focused on colour than melody and a quaver-by-quaver bassline that may be the first that beginner players learn. And it all works. The bassline feels great, the guitar and synths build and layer upon each with ever increasingly intensity, and all this allows Bono to give this love song a further dive into the spiritual with images of thorns and the bed of nails feeling like personal martyrdom (though the other having to give themself away showing the struggle for both). The way these first three tracks work together make themselves into a little three act narrative all into themselves.

Of the first side song, “Bullet in the Blue Sky” is probably the weakest. Mainly it is down to that refrain and almost spoken word section, wherein all the anger and intensity possible for the track reveals itself to all be a little too rehearsed. Still, the hardest song on the album – befitting a song inspired the US intimidation of El Salvador – it is some genuinely great instrumentation, especially that blues-style guitar solo piercing that said blue sky, and the snare led drums hit anchoring everything together. But the record then immediately moves on to another gem in “Running to Stand Still” (maybe they could then “slowly walk down the hall, faster than a cannonball”. Noel Gallagher is a noted fan of this song). As Bono says “into the arms of America” in the previous track, here the Americana influences are at their most obvious (if the gospel and blues solo didn’t already reveal themselves). The slide guitar introduction – and the harmonica solo that caps the track off(!) – help to colour the whole song as quite bluesy, even if it is actually more a simple piano ballad dedicated to the horrors of heroin addiction (I personally can only go off the documentary Trainspotting, but the eighties must have a great/terrible time for heroin).

Side Two begins with probably my personal biggest surprise of the album with “Red Hill Mining Town.” It might be the “driest” track on the album, with very little in way of delay coming from the Edge’s guitars, but it serves a great counterpoint to the synths and return of gospel voices (it also definitely has a country element, and the band seemed to intend that with the once unreleased music video in which they play “The Dalton Brothers,” which is the first noticeable case of the band playing with alter ego’s). The high notes here are incredible – something that Bono has never really been able to perform live on stage – and it all serves to depict the perfect atmosphere of a town stricken by the closing of the mines (a somewhat contentious topic in the eighties). “In God’s Country” meanwhile is the most U2-y song of side two, particularly a showcase for the Edge with many different variations of guitar and another great and simple solo. It’s probably the most filler of all the tracks on the album – the band in interviews seem to agree – but it still maintains a great tone and lyrics relating to flames and, of course, religion that certainly fits in with everything else.

“Trip Through the Wire” is also not one of the album’s strongest songs, but hearing the band play this kind of blues rock whilst still maintaining such a U2 feel has its fair share of charm. The instrumentation goes from choral to having a skipping quality, and the harmonica adds rather than subjects. “One Tree Hill” meanwhile might be the most overlooked songs on the album. Using the same improvisation/jam technique that they had The Unforgettable Fire, though here perfected, this track feels that it takes from so many styles that have occurred throughout the album (the coda in particular almost sounding like a different song), and the loose style helps to make this tribute to the band’s roadie and friend Greg Carroll feel all the more personal. So personal that apparently Bono couldn’t record a second take, and that vulnerable quality to the vocals where others are much more bombastic.

The Joshua Tree ends with maybe its darkest sounding songs. “Exit” – ironically recorded on the last day of recording – in particular is one of U2’s darkest, taking place from the mind of a killer, and despite the Eno connection doesn’t have the funny kitsch value “Psycho Killer” can (I know Eno didn’t produce that, let me have my strained connection!) with Edge, Mullen and Clayton playing to an overpowering, somewhat overbearing, intensity. It might be seen to be somewhat antithetical to the rest of the album optimism, but with the main character “wanting to believe in the hands of love,” one could see it as the opposite side of the same coin; that American optimism is open to even its most vile civilians. Plus the eccentricity moves straight on to the final track, and the scratching strings of “Mothers of the Disappeared”. Adding to the tradition of a slower song for the album’s outro, this one still goes for an epic feel, with really unusual and creepy sounds coming from the droning drum/drum loop combination to the darkness of the bass to that Spanish guitar, everything comes together in something that is both eerie and ethereal, and in some ways predates the sounds and sonic experimentation that would go on with Eno and the band for Achtung Baby. The better of the two songs dedicated to El Salvador, Bono’s vocals after a lot of the aforementioned bombastic is quiet and ultimately sad, and the night which “hangs like a prisoner/stretched over black and blue” feels like the right end to an album which began with calls of light.

The Joshua Tree was the triumph the band strived from, both artistically and commercially. Bands after it have tried to match its equation to various effects, from areana rockers from Radiohead to Coldplay to Snow Patrol, and its influence can even be felt in the Eddie Vedder-areas of the grunge scene. Everything the band did after this record was in some way a reaction to the massive impact it had.

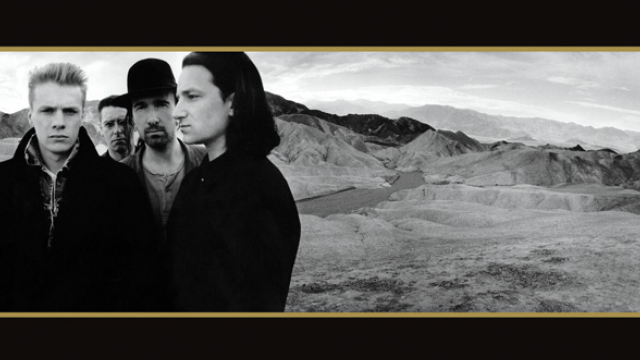

To others it was a monument to self-importance. From the reaching scope of the album themes to Anton Corbijn’s cover of the desert, the band cramped to one side, with ponderous and somewhat glum expressions on their faces. What kind of world famous band is too unhappy and important to be so?

But that kind of arrogance doesn’t tend to bother me. When I am listening to album, the artists in themselves just become characters to a cause rather than something I worry about in this world. Whether that be Stephen Morrissey’s heightened poetry, or the journey’s we take into Kanye “Yeezy” West’s strange mind, or indeed the sheer bravado of Bono Vox. All this is what gives The Joshua Tree its monumental heft, its commitment and ambition to things greater, and the means to stand as a classic.

I mean, what would U2 have to possibly do to get on my nerves?…

What did you think, though?

U2 Album Rankings

- The Joshua Tree

- Unforgettable Fire

- War

- Boy

- October

[PS: Remember that the next article will also be a movie review]