Most cinematic bank robberies and other assorted heists result in betrayal, backstabbing, and disaster. But does it have to be that way? The Lavender Hill Mob suggests that even when stealing a million quid’s worth of gold bullion from the Bank of England, the real treasure is the friends that we make along the way.

Alec Guinness plays Henry Holland, a mild-mannered bank employee responsible for the transport of the gold. For 20 years, he has overseen the deliveries, building up a reputation as a stickler for detail and a totally honest man; however, for the entire duration of his employment, he’s been working on a scheme to rob his own bank and live in luxury. There’s just one detail missing from his plan: a way to smuggle the stolen gold out of the country.

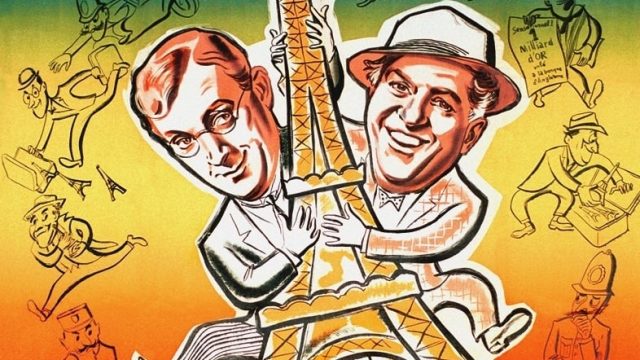

Fate finally delivers, as a new resident arrives at Holland’s boarding house — a budding sculptor whose day job is the manufacture of tacky lead Eiffel Tower paperweights for export to Paris. With easy access to a foundry and a ready-made trade route to the continent, Mr. Pendlebury (Stanley Holloway) perfectly fills the hole in Holland’s heist, and plotting can begin.

Of course, a plan of this magnitude is too much for two men of limited criminal experience, and time is of the essence — Holland’s loyal service has finally gotten him the promotion he doesn’t want, and he will only be responsible for one more delivery. So, Holland and Pendlebury recruit a couple of lifelong crooks using a brilliantly idiotic plan — they loudly discuss the failing safe at Pendlebury’s warehouse in a variety of London locations, then simply wait for opportunistic criminals to arrive, and recruit them to their gang.

Decades of crime cinema have led keen viewers to expect one of a few things to happen from this point. Either the robbery itself will be a disaster, or criminal egos will tear the gang apart as soon as they’ve collected the loot. But this film is a little different — the four members of the gang get on wonderfully, and Holland has had 20 years to put together his elaborate, foolproof plan. While things don’t go entirely perfectly, the gang improvise beautifully — whether this means Holland having to rough himself up to solidify his alibi or Pendlebury talking his way out of the police station after being pinched for an unrelated crime of absent-mindedness.

Much of the film’s charm and wit comes from the good-natured criminal comrades — these are the same kind of crooks that populate the cheerful prison in Paddington 2. It’s impossible not to root for this unusual gang of friends as they team up to make the bank (boo!) and the London police (double boo!) look like idiots. But, this being the early ’50s, and with certain codes still being in place overseas in the world’s biggest cinema market, things must come crashing down eventually. And The Lavender Hill Mob finds a fun way to do it, a tiny linguistic misunderstanding between England and France spiralling out of control as Holland and Pendlebury are forced to chase their illicit golden Eiffel Towers back from Paris to a London girl’s school (!) and then a police exhibition (!!) as the plot finally begins to unravel.

The last act of the film is a chaotic chase, as our two heroes flee the collected ranks of the police in a stolen car, causing proto-Blues Brothers pile-ups soundtracked, due to haywire radios, by “Old McDonald Had a Farm.” And while everything might not end up quite as well as the Mob intended, there’s a subversive feeling that they — or at least Henry Holland, relating the story from his Brazilian hideout — got their money’s worth.

The rich run of films that Ealing Studios produced in the ’40s and ’50s is mostly remembered for Kind Hearts & Coronets (1949) and The Ladykillers (1955), both also starring Guinness. The Lavender Hill Mob is my personal favourite though. It’s a lighter caper than the dark wit of those other two films, but it has aged beautifully — from unexpected treats like Audrey Hepburn’s first major screen appearance to the cheekiness of Holland covering his own tracks and being hailed as a hero, it packs its 77 minutes with clever wit, visual gags and smart writing. It uses the classic concept of “Britishness” perfectly, taking the stereotypical “polite gentlemen” to absurd lengths — and allowing even the career criminals to quote Shakespeare and request a break from plotting to catch the cricket match.