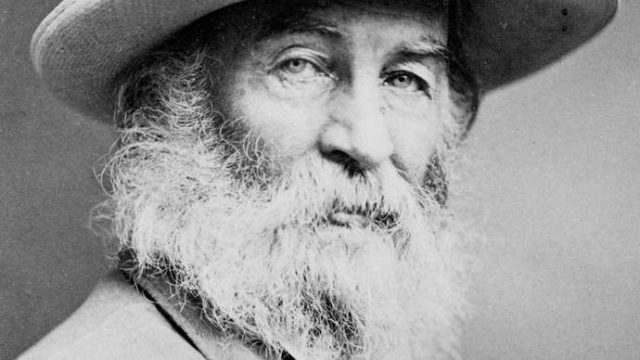

Before and after the pandemic struck, one of my main goals as a writer and reader was to finish all of the Deathbed Edition of Leaves of Grass (437 pages alone) by the esteemed (and self-proclaimed) poet of American life, Walt Whitman. Whitman is something of an icon of the Mid-Atlantic area where I live – his final place of residence is in Camden, New Jersey, and he famously walked around the ferries and railyards of Philadelphia, befriending people and drinking in the taverns on Market Street.

Even before I’d read Leaves of Grass, I’d absorbed chunks of “Song of Myself” and it naturally influenced my poetry – as did the Romantic and Transcendental schools Whitman himself never quite fit into but flitted around. I still didn’t expect the full breadth of Grass once I was 100 pages in, however. Much of Whitman’s ambition is truly fulfilled in “Myself” but the book itself is still staggering: posturing, erotic, cringey, lyrical, and unique, the work of an iconoclast able to see worth in anything and anyone. It’s his attempt to create an American poetic form distinct from the European standard, and I think it mostly succeeds. (Ironically he was celebrated more in England than America for quite a long time, in part because the obvious homo-eroticism of his poems cost him readers and support stateside.)

Whitman was more of a cult author in his lifetime than anything else, but he had serious devotees, even if some struggled with the sexual subtext of Grass. Dying in 1892 hastened his canonization here and elsewhere as a great iconoclast poet who came to heavily influence – for better or worse – the Beats and the Modernists.

I finished Leaves of Grass two years or so after first starting it in 2019. Reading Drunk Napoleon’s essay on the four qualities of a Great Artist then made me consider how Whitman himself fits into those conceptions. This is my own analysis of how Walt Whitman is that kind of creative mind, and how his famous contradictions (“Do I contradict myself? Yes I contradict myself”) complicate the work of his life.

Respect for the art – Whitman did write in other mediums, including an apparently terrible pro-temperance novel he hilariously later admitted to writing while under the influence. But he primarily wrote poetry because it would best capture America as he depicted it: a thriving place learning and wrestling with innate qualities and contradictions, one whose identity was expressed as a series of everyday actions rendered meaningful because of the omniscient narrator of the poems. In the preface to the book, Whitman even wrote “The proof of a poet is that his country absorbs him as affectionately as he has absorbed it.” There’s a nationalism in Whitman’s poetry that rattles me a little as an anarchist but I feel as American as he does, maybe just much more ambivalent about it. After all, I am engaging with this book at the point when the empire is teetering whereas Walt got kissed as a boy by the Marquis de Lafayette.

Leaves of Grass reminds me a lot of conversations I’ve had here and elsewhere about how artists need to understand the formal rules of mediums before breaking them. Whitman never finished school but was well-read, and knew the standards of the European verse and Romantic poetry, as well as contemporaries like Ralph Waldo Emerson (who would himself shower Whitman with praise before backing off when other colleagues were appalled by his work). Really Bible verses, especially the Songs of Solomon, were the greatest influence on him.

Part of his intent was to create a distinctly American free verse, no longer indebted to the poetics of Europe (or the region Walt might have called “the East”) but distinct to the lively, restless country it came from. Whitman broke with tradition but he had to know what he was splitting from in order to make something that genuinely startled readers.

A Puzzle To Solve: Whitman is one of many American artists to perceive the country as something whose identity must be understood and wrestled with. Leaves of Grass as noted above was his attempt at grappling with the new nation; the omniscient, sexual, and ecstatic narrator of these poems exists across all space and time but particularly in America, and he feels that he is with everyone and everything. “All these I feel or am.”

Fearlessness – Early drafts of more homoerotic poems were often changed for their explicit content, but the intent was always pretty obvious. Whitman wasn’t fearless merely in his defiance of standard poetics but also in linking his homoerotic feelings to a common worship of everything. “We Two Boys Together Clinging” even ties male companionship to a distinctly American way of living on the open road.

Walt Whitman was actually a fairly savvy promoter and businessman when given the chance, yet his sexuality and unconventional approach to writing would make him a cult author in his lifetime. “O Captain! My Captain” was probably his biggest “hit” and as the writer grumbled, it wasn’t really representative of his deeper work.

Curiosity About Other People: Whitman’s greatest flaw is indicative of the representative democracy he served – namely that he could accept everyone in all but actual reality. In person, Walt Whitman was anti-slavery but casually racist, as was common with many Northerners. The funniest discovery of the Justin Kaplan biography* was that he was a devoted phrenologist and even mused about the notion at the end of his life after the pseudo-science had been completely debunked.

Whitman’s poetry was far more radical than the man himself, as the writer somewhat admitted. In a famous letter to a woman who’d fallen in love basically with the narrator of his poems, he tried to explain that the actual Walt Whitman was not the ideal WW of the book but a very separate figure. This meant Leaves of Grass tried to fervently embrace all residents of America: whether slave or worker or soldier, they are part of the nation and so their actions have greater weight. The book comes from a sincere desire to connect and to understand other experiences, if hampered by Whitman’s obvious nineteenth century prejudices (he oscillates between boyish admiration of Natives and a belief that obviously Manifest Destiny is inevitable).

Drunk Napoleon commented that in a great artist, these traits tend to intersect in interesting ways, and it was easier to see this with Walt Whitman once I began writing. All of his goals and eccentricities as a writer complimented each other and resulted in a unity of intent and expression that makes the best of his poetry still unfathomably beautiful.