For those who came in late: I have been characterising the Metal Gear Solid series of video games as oddly resonant with the five stages of grief. First, there was Metal Gear Solid, an extended meditation by its creator Hideo Kojima on war, love, nuclear weapons, the human spirit, and the way action movies can influence the way we see all of these things. It was supposed to be a full stop at the end of a sentence. Kojima found himself surprised and baffled by the response – fans uncritically identified with its haunted antihero Solid Snake, missing or ignoring that he was a deeply unhappy and lonely man who was fooled into using his skills to support a bureaucracy based on blood money, and they demanded a sequel where they’d get to play as him again. So he gave them a sequel and crafted it entirely around Anger. Specifically, the anger of a teenager – cocksure, passionate, high on his own sense of being right and absolutely thrilled to get to be the one who lays out how things are and how things should be. Audiences did not respond well; time has given it a small but passionate fanbase who hold it up as, if not the Citizen Kane of video games, at the very least the Breathless of them. But at the time, the response was overwhelmingly negative; many found it impenetrable and did not get what it was going for – and most importantly, demanded a sequel to fix this egregious error and wrap up the plot points it brought up, massively missing the point of why they weren’t wrapped up.

Kojima saw this, reflected that perhaps this hadn’t been the best way to achieve what he’d been trying to do, and embraced Bargaining. Metal Gear Solid 3 made largely the same points the series had been trading in, but in a way very accessible to the action movie testosterone-overdosing fanboy’s sensibilities; the hero was a gruff cigar-smoking copy of Solid Snake (although technically Snake’s a copy of him) living out a goofy but very sincere riff on James Bond and Rambo. As with each game before it, the intention was to end things here; it explains the mythology and many of the names that were dropped in previous games. I believe Kojima is most interested in the motivations that drove the creation of the institutions that hang over the later parts of his timeline, and that’s what he expends most of his energy on; the series as a whole is a fantastic example of what TV Tropes calls Jigsaw Puzzle Plotting, in which we are given different facts at different times and we’re expected to fit them together into a whole on our own time, and the third game is a particularly spectacular example of this. For example, we’re given enough clues to realise that Ocelot is actually the baby that Big Boss’s mentor gave birth to on the shores of Normandy, and this is never spelled out because who cares? Not Kojima.

Except, oops, there were people who did care. They wanted to see mysteries explicitly solved, they wanted to see connections formally recognised, they wanted explanations for things that were unexplained, and most of all they wanted to see what happened to Solid Snake after the events of the second game. One of the big conceptual jokes of MGS2 is that we do not follow its protagonist – Snake has a very typical action movie plot going on in the background that we and Raiden only see pieces of, and at the end of the game he chases after Ocelot in what feels both like riding off into the sunset and reaching the end of the first act of his own current story. The point is clear to me: Raiden is at one point on his own journey and Snake is at another point on another. But what we do see is specific enough and big enough to spark the imagination in a way that, say, the final shot of The Shield is not and does not – Ocelot, seized by the soul of Liquid, has ridden Arsenal Gear through the city of New York, causing massive carnage. How will Ocelot react to Snake chasing him? How will Liquid? Will Ocelot fight against Liquid or try to reason with him? Will Snake have to kill Ocelot and Liquid? Will Snake turn one against the other? How will the military industrial complex respond to the damage to New York? The public?

Metal Gear Solid 4 was released in 2008 – five years after the third game – and immediately dove into these questions by showing where Snake was a few years after those events. He’s still chasing Ocelot with the assistance of Otacon, and Ocelot’s personality has been fully supplanted by Liquid. The Metal Gear has completely changed the face of warfare, both directly in that there are ‘Gekkos’ – smaller autonomous Metal Gear-like creations that rapidly changed the terrain of the battlefield – and indirectly, in that there is now a ‘war economy’. Full disclosure, this is one of the rare cases where I never fully grasped what Kojima meant, but the idea is that war has become a supermarket-like industry in which entire nations are solely supported by its existence. People smarter (or at least louder) than me have talked about how this makes absolutely no sense and that war is generally a drain on an economy, not a supporter of it. But it’s really here as a part of the overall emotional affect – or rather, it’s here because with MGS4, Kojima reached the Depression stage.

To explain this, it’s worth comparing with The Sopranos. That show is defined by conviction – not just conviction that the things it depicts are Evil, but that it’s damned Evil. There is absolutely no way for Tony or Carmella or AJ or Paulie or any of them to change, and anything they do to try is futile. By comparison, MGS4 is driven by confusion. It doesn’t understand why none of the things it does have worked and it doesn’t understand how to bring its dreams into reality. The first three games covered an expansive range of themes and tones but not only lashed them together into a single journey, they made them feel like this was the best order for maximum emotional impact. The fourth game feels more like someone trying to make sense of something, and any recurring ideas are because the auteur can’t get them out of their head. We are not watching an artist generate great work, we are watching someone grumpily mumble to themselves; the fact that Hideo Kojima has all the qualities of a Great Artist can sometimes make this interesting but never quite overcomes that problem. The most potent symbol of this is that, for the first time, the protagonist isn’t someone the player is expected to identify with but an avatar for the storyteller.

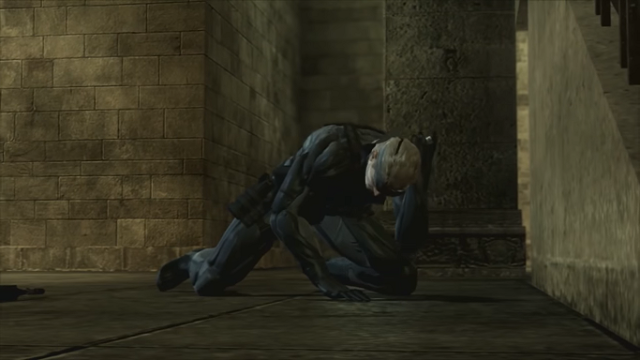

At the beginning of the game, Solid Snake has been ageing rapidly as a result of his status as a clone; he’s barely in his early forties but his hair has turned completely white, his skin has become heavily wrinkled, and his muscles and body have degenerated to the point that he’s supported by a) a Sneaking Suit that increases his physical strength as well as massaging and maintaining his body and b) a series of injections he takes whenever his body starts really falling apart (represented by coughing fits he occasionally has). The thematic point is as clear as always; he frequently admits he no longer seems to fit into or be relevant to the world. Meanwhile other characters react with surprise and disgust when they see him continuing to fight when he’s in no shape to, dismissing it as arrogance or a death wish, and he’s never able to fully articulate why he continues to fight despite his body screaming at him to stop. The youth of the world – most strongly represented by Meryl, returning for the first time since the first game as the leader of her own unit and a highly competent soldier equal to Snake – are now its movers and shakers, contemptuous or indifferent to Snake.

A big part of the tone of the game follows through on this – it’s sullenly and resentfully going through the motions. If the plotting before was like being handed the pieces to a jigsaw puzzle, this is like watching someone put the pieces together for you, and not in the cool fandom way like I’m doing (and that other MGS fans have done before me) but in a ‘fine, whatever, fuck off’ kind of way. We’re given the most literal-minded explanation for the events of MGS2 that you could possibly imagine. We’re given cameos and references to almost every living character and a few dead ones. Perhaps most offensive to me as all – as a player and audience member, not in any political context – is crowbarring the characters of the third game into the wider mythology in a way that felt implausible to the characters and violating the spirit of what I enjoyed about the games. I could see EVA turning out to be the mother of Snake, Liquid, and Solidus because of her considering Big Boss her true love, and I could see Major Zero being equally traumatised by the events of the third game into becoming a major part of the conspiracy. But having Paramedic become Dr Clark (who created the Cyborg Ninja of the first game) and Sigint become the DARPA Chief (who is killed before the events of the first game and impersonated by Decoy Octopus) seems unnecessarily meanspirited.

Worse, it violates that sense I always got from the games that no individual is capable of controlling, leading, or even driving the systems they are a part of. Part of the reason I can roll with – even enjoy – the ridiculousness of the franchise is that however ridiculously overpowered a character is, they are still just one person amongst a seemingly infinite amount of them. An individual can be judged and held responsible for their actions and that can and will be satisfying, but stopping one of them will not change how the world works. Making every character an important part of the conspiracy’s construction feels more like a conspiracy theorist’s dream of a cabal of world leaders rather than patterns of human nature playing themselves out again. And the thing is, I don’t get the sense this is a deliberate act of political thought on Kojima’s behalf – I think he’s just using a cheap device to placate what he sees as a continuity-obsessed audience to stop them asking what happened to Paramedic and Sigint. You can also see it in the return of Vamp, who continues his rivalry with Raiden that’s imbued with homoerotic undertones, but in a way that’s more forced than the gleefully queer series can be – Vamp cuts up Raiden and gets covered with his white blood, Vamp seems to die only to magically return for no reason, Vamp licks Raiden, etc.

(Like Snake, Vamp also longs to die)

The big deliberate political/thematic thought that underlies the game is the question of legacy. One recurring idea here at The Solute is the idea of art that exists to Make A Point, and if you look at the MGS games as the journey of an artist, you see what happens to someone who really commits to doing that – the emotional cost of Making Points. For three games and ten years, Kojima has been trying to pass on his ideals of peace and love, only to see them thrown back in his face; his approach has always been “okay, that didn’t work, I’ll try another way”. The fourth game shows him in a state of complete disillusionment. When Raiden returns, he’s become a bloodthirsty killer nihilistically butchering people and keeping no emotional attachments and spouting poetry on how sad he is that’s inspired by the exact words Snake told him; it’s a complete betrayal of his arc in the second game and Snake is shocked and saddened and remarks “Raiden, that’s not what I meant.”*. There’s a sequence where a character says “The games have to end,” as the box art for previous games in the series flies past the screen. The climactic scene of the game is Big Boss, brought back to life in a plot turn so ludicrous (even for this series) that many interpret it as a dream or fantasy Snake is having, reflecting on the pain and misery he’s brought into this world by misinterpreting the will of The Boss and concluding: “The world would be better without snakes.”

*Naturally, fans decided Raiden was cool now.

How I’ve felt about this has largely depended on where I am emotionally. The first time I played it in my late teens, I was still enamoured with the punk rock passion of the second game and saw all of this as an unpleasant and cowardly betrayal. When I replayed it about half a decade later, thoroughly disillusioned by my experiences with the Left and feeling as if I had learned and changed nothing, I found myself a little more sympathetic. Coming back to it now, I feel not so much a more nuanced view as I do feel everything and more, all at once. When you’ve been successfully changed – even a little – by someone Making A Point, it can be easy to believe that it’s that easy to do it to everyone, I suppose. And when you’ve utterly failed at a task you’ve set yourself – indeed, when you feel like you’ve actively made thing worse – and you don’t see any way through, it can be easy to fall into depression. Now that I think about it, ten years of Metal Gear Solid doesn’t seem like a very long time; reflecting this, in the time since I was playing MGS4 in a state of disillusionment, I’ve seen the state of the world change and I’ve seen long-lasting good things come as a direct result of my idealistic actions. But I also know I had no reason to know that was coming at the time, any more than Kojima could have seen me coming amidst the waves of fanboys.

It’s also that I can now see that those fanboys weren’t really wrong for wanting what they wanted either. What they were after was satisfaction from a dramatic structural perspective – to see the final consequences for actions that had been set up. It’s also hard to deny how even many of the cheap moves the game pulls are emotionally affecting. The game introduces a small new gameplay element: during cutscenes, when an X appears in the corner, the player can press the X button repeatedly to see and hear flashbacks related to whatever the characters are talking about. There is something sad, wistful – yes, nostalgic – to these flashbacks and seeing how long the journey has been. It’s genuinely entertaining when the puzzle pieces come back and actually drive the plot forward – my favourite plot turn in the game is the revelation that the remains of Big Boss that the characters have been chasing around are actually the remains of the long-forgotten Solidus Snake (something hinted at by the fact that said remains are missing the wrong eye). Most of all, there’s the return to Shadow Moses Island. Having you and Snake pick over the remains of where you first met, hearing all the flashbacks and seeing how your journey together was set in motion and how much time has passed since then is genuinely moving; the climax, in which you pilot Metal Gear REX in a fight with Ocelot piloting Metal Gear RAY is balls-to-the-wall awesome and the part of the game that has the most life in it.

(I actually didn’t play through Metal Gear Solid 4 for a long while – I watched my best friend play it, because he owned a PS3 and I didn’t. REX has a small laser positioned between its legs that we naturally referred to as a ‘penis laser’. During the fight in the fourth game, he was only using the penis laser. I said “You gotta use something else, you’re not gonna kill it using the penis laser.” Friends, he killed it using only the penis laser.)

Part of the reason I’m so averse to art that exists to Make A Point now is because I’ve seen what can happen to an artist who genuinely holds that as the highest ideal – who doesn’t just want to articulate what they believe, but to bring other people around to believing it. Kojima made his points, and when he saw they didn’t land, he didn’t just dismiss his audience as idiots, he tried to adjust his process and rearticulate it in a way they could understand. In discussing the second game, I was showing the limitations of Point Making in how even a True Believer, already primed to agree and already speaking the same language, can still find themselves wanting when it comes to expressing those ideals, because a good story isn’t the end of a sentence, it’s the beginning of one; you don’t get to decide how it ends, the audience does. With this, we see the other side of things – the cost that comes with trying to change the world through art and pretty speeches. He tried – he really tried – to explain his beliefs and feelings in such a way as to be understood, and that lead to three really great games, but in the end people will only ever tell the story they want to tell. The longer it takes to accept that, the harder it hits.