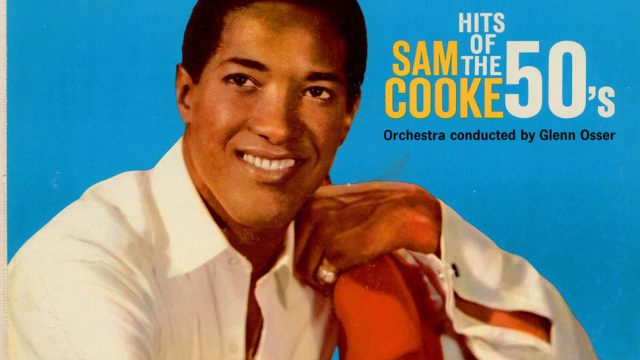

There are few soul singers, or any singers, as universally beloved as Sam Cooke. But even his exalted place in the canon doesn’t account for much of his best work. The conventional wisdom holds that he only came alive in his singles, especially when he wrote them himself. Except for Live at the Harlem Square Club, and maybe Night Beat or his gospel records on the outside, most of his albums get dismissed as undistinguished filler, the great man demeaning himself in the futile hope of appealing to a wider, whiter audience.

Our old nemeses at Allmusic dismiss Hits of the 50’s [sic] as “one of the records that for many years — in the absence of his best material being available — blighted Cooke’s reputation as a soul singer.” Biographer Peter Guralnick says it “could just as easily have been called Hits from Your Father’s ‘50s.”

They’re not entirely wrong. Hits of the ’50’s tracklist is notably bereft of what modern listeners would think of as the sound of the decade — not a lot of Elvis Presley or Little Richard, but a whole lot of the standards and show tunes that were already on their way out when the decade began.

And the liner notes come right out and say why. “When rock hit the Fifties, a lot of sensitive [read: old, white] citizens corked their ears, crawled into their woofers and occasionally sent messages to the outside world, demanding, ‘Where is the good new music — and where are the good young singers?’” It describes Cooke as “tall and slender, with looks that remind you at once of Belafonte and Poitier” — two artists with little in common with each other, or Cooke, except they’re both clean-cut Black men who white America found nonthreatening.

But as they say, you can take Sam Cooke out of soul, but you can’t take the soul out of Sam Cooke. If Nina Simone was the last of the great all-around entertainers, it was only because Cooke beat her into the studio by a couple of years. Few of these songs can compare to Cooke’s own compositions, but he rarely sinks to their level. He raises them to his own, somewhere above the clouds.

Before we go any further, there’s another elephant in the room. Sam Cooke died young in a way that not only cut his career short but tarnished everything up to that point. In 1964, he was shot to death in an LA motel, allegedly in the midst of a sexual assault.

We’re coming to a long-overdue reckoning on what sexual abuse means to an artist’s legacy, and few cases are more difficult than this one. The oft-quoted statistics proving that false rape accusations are several orders of magnitude more common in the popular imagination than reality come with one big asterisk when it comes to Black men, who were lynched by the hundreds on false accusations. The documentary The Two Killings of Sam Cooke makes a persuasive case for Cooke’s death as a lynching by proxy in light of the danger his Civil Rights activism posed to just about everyone with any measure of power. But it also gives his surviving friends and family the floor, and what they say sounds all too familiar from endless defenses of men we know are guilty — impugning the victim’s character, insisting “That’s not the man we knew.”

No one who wasn’t in that motel can say for sure what happened, and the more I learn, the less I feel I know. But I can’t in good conscience spend the next couple thousand words telling you how great Sam Cooke is without acknowledging the possibility that, in one far more important way, he may have been anything but.

The beauty of Cooke’s music makes it easier to understand, if not forgive, why so many people reject that possibility. When he hits and holds those high notes, he sounds like an angel — a cliché, but only because writers rarely find a subject as deserving as Cooke. And when he hits those low notes, he sounds like no other singer who ever lived, hitting a pitch that would sound flat if it weren’t so superhumanly smooth.

Listening to how much more comfortable Cooke sounds with his rawer, bluesier style on Harlem Square, I began to understand why so many listeners consider his other albums compromised. But until then, I couldn’t believe it was possible for him, or any singer, to sound more comfortable than he does on these easy, relaxed vocals. Listen to Hits of the ’50s and your worries melt away. It’s a reminder that “easy listening” wasn’t always a put-down. Cooke may be a stranger in this country, but he beats the natives at their own game.

It takes a moment for Hits of the ‘50s to reveal itself as a masterpiece. The opening instrumental from producers Hugo and Luigi and conductor Glenn Osser could have come from any hundred records of the era. And Cooke doesn’t pull out the pyrotechnics that will define the album’s highlights just yet.

But he’s still quietly performing his alchemy, turning the song into gold. The original was incongruously stodgy, operatic, and, ultimately, flat. Cooke takes it on a journey, varying up his performance in unexpected, jazz-inflected ways, suddenly going high at the end of the line “Is it all going in one e-e-ear?” or the middle of, “Won’t take this advice I hand you like a brother?” No one else would think to do it, and yet it works so well it seems perfectly natural.

But when Cooke starts with gold, his alchemy turns it into something else altogether, and that’s what he does with the Nat King Cole classic “Mona Lisa.” Despite the producers’ and arranger’s role in jamming Cooke into that square hole, Osser does excellent work here — for the first of many times on the record, he makes a trumpet sound like the saddest, loneliest sound in the world, so beautiful it’s easy to forgive the cheesy harp and flute that follow a second behind it.

And then there’s Cooke. With his gorgeous falsetto, he draws out every note, never a fraction of a second too long. He invests each one with deep, soulful sadness, not just for his own unrequited love but with empathy for the “cold and lonely” woman he sings to. (Remember how when asked to define soul, his answer is just a few, non-verbal notes.) And Hugo and Luigi know what to do to make that performance shine even brighter, layering just enough subtle reverb to give his voice a haunted, haunting power.

After that, we’re back to song choices with nothing but Cooke to make them sing. But he does. There’ve been a million songs on the same basic theme as “Too Young.” But in the ending refrain, “Then someday/they may recall/we were not too young at all.” Cooke finds notes in the word “recall” I don’t think any other singer knows exist.

“The Great Pretender” is similarly well-trod ground, even seven years before “The Tears of a Clown,” but instead of following the Platters’ lead of turning it into an incongruously cheery pop tune, he invests it with soft, bone-deep sadness. And for all that Hugo and Luigi steered him away from challenging his listeners, they give Cooke a challenge by suddenly switching to a martial beat in the last verse. He’s more than up to it.

The centerpiece of the album is, fittingly, right in the center, where Cooke closes off side one with what has to be one of the five or ten greatest songs ever recorded. Despite the album’s title, “Unchained Melody” wouldn’t become the superhit we think of today until the Righteous Brothers got ahold of it in another five years. That one’s pure pop bombast, but Cooke’s is softer, subtler, and far more devastating.

That sad, lonely trumpet starts things off before Cooke proves his voice can be even sadder. He cuts through the chintzy kitsch of the production, his intonation of “mine” reaching to the heavens before coming back down in what sounds like an anguished whimper.

He packs ten notes where most singers would struggle to hit one. The best love songs suggest emotions even bigger than love, and Cooke’s “Unchained Melody” is pure, transcendent yearning. As much as anything by such a celebrated artist can be, it’s an undiscovered masterpiece, and I have to admit I felt vindicated when Bumblebee pulled it out to score one of its most emotional scenes.

Hugo and Luigi attempt to push at the boundaries of Cooke’s appeal again when side two starts with “The Wandering Wind,” a full-on country song — they even lay some cheesy clippity-clopping under the vocals, for fuck’s sake! You have to wonder if it’s an act of sabotage, but if it was, it doesn’t work, and Cooke’s voice sails above everything they throw at it, unscathed.

The only song Cooke struggles to save is “I’m Walking Behind You,” a deeply creepy stalker anthem (just look at the title!) about a man who can’t get over his ex even as she’s marrying another man, and who seems to be actively rooting for her marriage to fall apart so they can get back together. But even with these handicaps, Cooke’s voice is so effortlessly beautiful it took me multiple listens to realize just how skeevy the whole thing was. After all, how could that voice be saying anything wrong? Give some credit to Osser here too — he dials back the excess a tad for this one, and that high, airy flute is almost as hauntingly beautiful as Cooke’s high, airy falsetto. Almost.

“Venus” seems equally unpromising — a blatant ripoff of “Mr. Sandman” asking the goddess of love to “send a little [ew] girl for me to thrill.” And yet this was the track that grabbed me by the collar and made me realize I was in the presence of greatness in my first, half-distracted spin of the record. It should be clear by now that Osser does the most when he does the least, and that’s certainly true here. His backing is uncharacteristically minimalist across the track, rarely letting more than one or two instruments into the mix at a time.

But the most heartbreakingly beautiful moments of “Venus” are just Cooke’s voice — and his voice, and his voice, as the producers let it echo to create an endless, cavernous sonic world.

And really, isn’t that what all Cooke’s music does? The Man Who Invented Soul built a new world where none existed before, taking other writers’ songs as the building blocks to construct something totally different. And, if just for a few brief years, he got to share it with the world.