“One needs a theory for everything.”

A Scanner Darkly is a simulation of the experience of being an American drug addict at the end of the Sixties. Philip K Dick’s books aren’t stories so much as they are essays; for him, creativity means coming up with as many interesting things to do with the topic as possible, and discipline means staying on topic and not wandering off. This book was inspired by Dick’s experiences following his divorce in which he turned his home into a halfway house for dope addicts before falling into a cult for a short while, and that gives him a centre of gravity to honestly show different thoughts and attitudes related to drug addiction. In his author’s note at the end, Dick says that the book did not have a moral, but if it did, it would be that addicts are being punished beyond what they deserve for the crime of trying to have a good time all the time. My take was that addicts are more of a danger to themselves than to anyone else; about halfway through the book and apropos of nothing in particular, it hit me how absurd the amount of effort and money the police were pouring into tracking the lives of people whose sins were so petty as to be nearly meaningless.

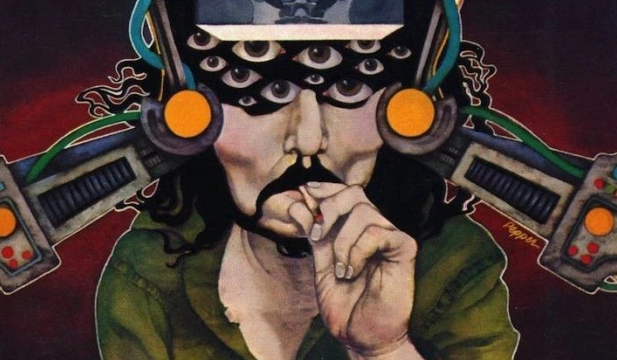

The interesting thing about treating an artist’s work as self-expression is seeing older ideas they explored sublimating themselves within later works – ideas that are taken for granted like a scientific theory. Dick wrote many works about empathy and lack of empathy, and much of A Scanner Darkly is about the way people dehumanise drug addicts. There’s extended discussions on the way the ‘straights’ see them – bloodthirsty freaks who would kill animals and destroy priceless works of art at a moment’s notice – with the protagonist (a man who isn’t so much nameless as suffering an overabundance of them) reflecting that, if anything, most of the addicts he knew were more caring and kind to animals that the straights would have put down. The premise is that our antihero is an undercover agent within the drug culture, and his double identity situation (amplified by scifi tech that makes his physical appearance completely unknown to his cop allies) ends up cracking completely when the drugs he takes as part of his cover literally split his brain and identity in half, and one upshot of that is that we see a man lose his ability to empathise with himself.

Dick was an anti-authoritarian, and one thing he recognised was how authority can mess with one’s ability to empathise. The protagonist’s cop identity, SA Fred, ends up drifting further and further away from being able to even comprehend his other half’s actions, and when he discovers the link between them, he’s disgusted. Early in the novel, before he fragments, the protagonist has to infiltrate a rehab facility that a drug dealer may have used to escape the authorities, and facility workers treat him like a cross between a disobedient child and a cockroach – he is disgusting vermin who should be grateful for the chance to redeem his sorry ass by being demeaned by them. Mental health treatment has come a long way, and a big part of it is treating the sick (which absolutely includes drug addicts) not as problems to be solved and certainly not as moral questions but as individuals with the right to determine the direction of their own lives; Dick presents the full horror of people who believe themselves as deserving control over you. He puts it in the right place in the narrative, too – at this point, the protagonist has it together enough that he’s fully aware of how little control the rehab staff actually have, and his humiliation under them is compounded by the fact that he knows more than they do.

This book is not, however, a pro-drug narrative; it also shows the lows of destroying your mind and body with chemicals. The very beginning of the novel effectively shows why a drug-based lifestyle is cool – it’s almost a procedural in the goals a drug addict must have on their mind day-to-day – but it all falls apart pretty quickly (with occasional references to the earlier glory days of the characters). Our protagonist lives in squalor with a bunch of assholes with cops and straights harassing him every day, and he’s crumbling under his addictions. The paranoia he develops ends up curtailing his empathy – maybe not to the extent that being a cop or a rehab staffer does, but enough that he’s looking at how to use people rather than seeing them as beings in their own right. The characters all have their own quirks that drugs are either amplifying or twisting; Barrie is an arrogant know-it-all and what intelligence he does have is pushed into the utterly inane, Fleck is incoherently useless, and at one point all the characters become confused by a bike they come into possession of. This manages to achieve what, say, Reefer Madness failed to do – present taking drugs as something awful – because he’s doing it from the inside and without judgement. In effect, he creates a situation in which I can empathise with drug addicts; drug addiction doesn’t sound like it’s for me, but I understand.

My understanding of addiction is that it’s a social phenomenon as much as a biochemical one. There was the experiment known as “Rat Park”, in which rats who were given large areas of social and intellectual stimulation were much less susceptible to addiction than rats kept in small cages. Cutting edge treatments of addiction are tied into social and spiritual development; I have seen addiction specialists talk about more common and socially acceptable addictions, ranging from alcohol to smartphone addiction, as coming from the same place as heroin and requiring similar solutions. My friends who are ex-drug addicts have often confirmed this for me, and I can see resonance with my own addictions. Dick’s underlying insight in A Scanner Darkly is that the existence of drug culture is a damning condemnation on the straight world – all this is terrible, but it happened because the straight world is miserable and spiritually unfulfilling.

SCATTERED NOTES:

- I love Arctor’s parody of a Freudian explanation for Jerry’s behaviour.

- Dick comes up with a poetic compression of the straight morality that chills me to the core: IF I HAD KNOWN IT WAS HARMLESS, I WOULD HAVE KILLED IT MYSELF

- Donna tells the story of a guy who saw God and then had to deal with the disappointment of living life. If that’s true, I got off easy with my reaction to “Every Grain Of Sand”.

- “I am not a character in this novel; I am the novel.”