The FAR has been programmed to shy away from the spotlight, no matter how dynamic and appealing its presence may be. Please, look instead on these articles about classic and not-so-classic movies, theatrical projection formats, musician mythologies, and the state of artistic culture as a whole.

The Psychic Johnny Smith, Drunk Napoleon and Rosy Fingers deserve attention and thanks for contributing this week. Send articles throughout the next week to ploughmanplods [at] gmail, post articles from the past week below for discussion, and Have a Happy Friday!

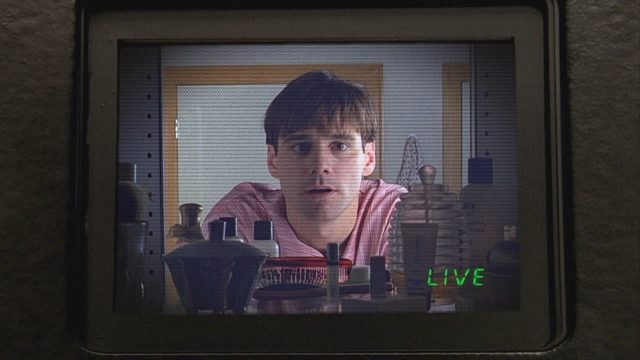

Dominic Corry at Letterboxd dives into reviews of The Truman Show, current observations from LB users during the pandemic and some crazy what-if scenarios from contemporary interviews:

The Vanity Fair article does, however, reveal a fascinating ‘what if’ scenario relating to Christof, the god-like director of the in-movie TV show played by Ed Harris, who offers up a pile of pretentious auteur clichés: mononymous, beret, etc. (beyond the whole god thing, that is). When Dennis Hopper, originally cast in the role, wasn’t working out, Weir considered playing the role himself, which would’ve added yet another meta layer. It brings to mind how George Miller styled Immortan Joe (played by Hugh Keays-Byrne) after himself in Mad Max: Fury Road, or how Christopher Nolan’s haircut shows up in most of his films. And, at one point, it could have gone mega-meta. Weir, in the 1998 interview, talked about a “crazy idea” he had, a technical impossibility back then but easily achievable with live-streaming now. “I would have loved to have had a video camera installed in every theater the film was to be seen [in]. At one point, the projectionist would … cut to the viewers in the cinema and then back to the movie. But I thought it was best to leave that idea untested.” Imagine.

Film School Rejects muses on a preference for projected film:

But how much of the appeal is technological, and how much is psychological? This can be analyzed from these two different standpoints. Color film generally brings forth more vibrant colors than digital. Because of this, the image is pleasing to watch because we are evolutionarily programmed to pay attention to bright colors, as they signify predators and poisonous things. We stay alert when watching film and are thus predisposed to feel more connected to it. In addition, the gentle outlines are easier on the eyes than what are primarily cold outlines of digital pictures, so it is not a strain to watch.

At The Guardian, Scott Tobias “celebrates” the 20th anniversary of Michael Bay’s “historic” “epic” Pearl Harbor:

The banality of the plotting here, courtesy of the Braveheart screenwriter, Randall Wallace, is self-evident and noted in nearly every review of Pearl Harbor, which opened, as all Bay films do, to poor notices and robust box office. But the truly damning detail – one that extends beyond the love triangle and into every other aspect of the film – is that Rafe and Danny are interchangeable. It doesn’t matter whether Evelyn spends the rest of her life with one or the other. (In fact, she doesn’t have a choice!) Maybe one is a better lover and the other more emotionally generous. Maybe she shares more interests with one than the other, or maybe there are differences in values or politics or preferred pizza toppings. Whatever particular qualities might separate these two humans are rendered so irrelevant, in fact, that Evelyn tells Rafe that she’ll never look at another sunset without thinking of him. This despite the fact that it’s Danny who sneaks her on to an airplane to see Pearl Harbor at sunset. These three are really into sunsets.

For The New Republic, John Semley’s review of a new Dylan biography is both a hilarious roast of a self-styled Dylanologist and a thoughtful exploration of Dylan’s mystique:

Dispelling Dylan’s various myths, self-styled and otherwise, also has a diminishing effect. It’s like explaining a magic trick. Throughout his career, Dylan’s identity mutated—from warbling folkie to motor-mouthed rock poet to country troubadour, Christian evangelist, and beyond—as he followed his muse, or his whims, or whatever. He defies expectation and seems creatively beholden to not much beyond his own shifting fancies. I imagine this is why most people like Bob Dylan. Because this is why I like him. And if other people like him for other reasons? Well, then that only certifies his status as the man of manifold possibilities, a Bob for all seasons. Rifling through old letters and contracts for clues to the “real” Dylan can feel a little beside the point, like fact-checking The Iliad against archaeological excavations from ancient Greece. Does [biographer Clinton] Heylin expect to find some smoking gun, a scrawl in an old journal reading, “I am going to make a point of performing my identity, to vex and frustrate the public, and particular critics and biographers?” Such a po-faced confessional seems unlikely, and Heylin knows it. Even the titular “double life” conceit of these new biographies seems insufficient for an artist who recently boasted of containing multitudes.

Film Crit Hulk goes long on recent film studio mega-mergers, the tech industry and labor unions:

These are the conditions for the reckoning. They’re out of cash. And so suddenly, Warner Brothers is spinning off assets because of AT&T’s massive failure. Which means it’s the beginning of the end for the company that goes back to 1904. But much less reported right now was the fact that Amazon is in the process of buying MGM – which signals the most dangerous shift with what is about to happen regarding labor. Because yes, this whole history thing has a point. After all, why should I care about the death of some giant corporation? How is this not more business as usual? And isn’t it okay that all this business is just going to the streamers? Aren’t we technically making more things than ever in Hollywood? Yeah, here’s the problem with the specifics of how it’s happening… It’s destroying the worker in the center of it.

And finally, in arguments that no doubt every Solutor will roll over and entertain without pushback, Ryan Murphy (not that Ryan Murphy) for Works in Progress gives evidence that logically all artistic endeavors of humanity must currently be experiencing their highest forms:

How do we know this means that the modern world is better? Because people don’t just copy and paste. All of these incredible works of the past are just sitting there waiting for you to enjoy them (with 80% or more of the impact of experiencing the original in real life) on YouTube, your local library, or Google Images. Instead, we choose to experience other things. Economists have a phrase for this: revealed preference. Our revealed preferences mean something, and it ought to be a baseline assumption, if nothing else, that if we are making the choice for one thing over another it’s because it’s better for us. To recapitulate: in a given field of art or practice, if we can replicate a near approximation of a historical masterwork at a cost no higher than it was in the past, and we’re doing something else, that something else is probably better than the supposed historical masterwork.