The ‘70s and ‘80s are often called a “dark age” for animation. That’s true in some ways. It was certainly true for the kings of animation over at Disney, which had fallen so far after Walt’s death that their The Black Cauldron got clobbered at the box office by a fucking Care Bears movie. And most other studios were out too, as the changing moviegoing habits of the post-TV world killed the short cartoon format.

But when the cat’s away the mice will play (or maybe the cat would be the Mouse in this metaphor? Anyway), and the absence of the industry’s biggest juggernaut cleared the way for newer, stranger kinds of animation to grow up around the margins of Hollywood. You can get away with a lot more when no one’s paying attention, after all. And even when the moneymen did get involved, some of the biggest successes of the era — Yellow Submarine, Fritz the Cat — proved that weirdness sold.

Enter Raggedy Ann and Andy: A Musical Adventure. It didn’t play very many theaters, and it hasn’t gotten a home video release since the days of VHS. But this weird, disturbing, haphazard contraption of a film played enough on basic cable that it lives as a kind of collective fever dream in the minds of the kids who grew up on it. Its path to cult status should already be clear from the description, but the guiding hand of one of the greatest animators who ever lived doesn’t hurt.

Richard Williams would later end the dark age almost singlehandedly with his groundbreaking animation for Who Framed Roger Rabbit? the following decade. In 1977, he’d already begun work on his unfinished masterpiece, The Thief and the Cobbler. He was doing stunning work on hundreds of commercials and TV specials in the interim, but his main goal was never more than to keep the lights on long enough to get Thief finished to his exacting standards.

Raggedy Ann, his first feature was one of these work-for-hire gigs. Maybe Fox knew no one else could bring Johnny Gruelle’s creation to life. Every fold in Ann and Andy’s bodies is drawn in exacting detail, and they flop around, their component parts responding to gravity in every direction, just as if a real boneless pile of rags had come to life.

The credits have elaborate, moving title cards for each of the animators — including many names that should be familiar from the credits on hundreds of classic Disney and Warner Brothers shorts — but none for the voice cast or story team, which should give you a good idea of Williams’ priorities. Unlike his decades-long process on Thief, his order for Raggedy Ann only gave him a year to complete it, an extensive timeline for live action but for animation, they might as well have asked him to break the sound barrier. To get Raggedy Ann finished to his standards in that time, he demanded access to studios on both coasts — which may have ended up working against his purposes since he spent most of the year flying in between them. In the end, Williams’ perfectionism clashed with Fox’s need to get it done on time and under budget. Foreshadowing his fate on Thief, he got booted off his own project just ahead of the finish line. Those elaborate credits? He paid for them out of pocket when Fox refused to pony up.

The final product is as unwieldy a patchwork as its supporting character the Camel with the Wrinkled Knees. The animation lurches from stunning to merely good to outright Hanna-Barberity, sometimes within a single shot. In one, a water skier kicks up a wake drawn with the detail of a Dutch Master, and in the next, the water’s turned into a couple quick scribbles. In another, the Camel with the Wrinkled Knees does an elaborate dance with Disney veteran Art Babbitt sweating over every wrinkle while Ann and Andy watch, frozen with stupidly blank expressions, apparently replaced with cardboard cutouts.

Even the most elaborate scenes Williams was able to oversee before his exile still have a veneer of ‘70s cheapness over them. Even if he wrung all he could out of his labor, his parts were still limited. The Xerox process Disney had introduced a decade earlier, which allowed animators to scan directly from the pencil art without inking, gives Raggedy Ann a wonderful graphite tactility but also dates it square to the ‘70s. And it makes even the most exacting sequences look unfinished.

Williams didn’t have access to the lushly hand-painted look that made Roger Rabbit so stunning, making do with flat, muddy colors. He compensates in the line art where he can — many of these characters swim with hundreds of cross-hatch marks.

The title is one-half false advertising, one-half warning. It’s certainly musical, maybe too much so. Sesame Street’s Joe Raposo contributed over twenty songs, and he refused to cut any of them. This means it’s so musical there’s not much room for adventure — the plot can only advance a few minutes at a time before it has to stop dead for another song. Most of them serve no purpose at all — Raggedy Andy gets a great big musical number called “No Girl’s Toy” that seems like a classic example of what musical fans call the “I Want” song, but Andy’s fragile machismo never comes up again. It is, at least, amusing to see Andy protest how manly he is in the most flamboyantly camp way imaginable.

It takes a half-hour of this one-hour-and-twenty-minute movie before the plot even starts. For comparison, imagine if it took all the way to the end of Fellowship of the Ring before the Hobbits even left the Shire. Then again, maybe that’s for the better, since the plot of this supposedly kid-friendly movie revolves around implied sexual violence, with a pirate abducting new toy Babette and Ann and Andy venturing into the Deep, Deep Woods to rescue her. Even worse, Babette and the pirate end up together in the end. On a more positive note, that Captain, with his yard-long mustache constantly twitching like a cat’s tail, is a perfect example of Williams’ design sense, which seems to be based on making everything as complicated to animate as possible.

Ann and Andy face all kinds of frightening obstacles in the woods, but none of this intentional terror is quite as horrific as the supposedly lovable toys, all huge, dead eyes and Cheshire Cat grins. Nearly every review mentions two identical, inexplicably naked dolls with awful, electronically distorted voices who keep talking in rhyme and unison at random intervals with sharp insights like “Really scary! Really scary! Deep, Deep Woods are really scary! Whoa-oa!” That last one’s the worst of all, ending with the two of them jamming their faces all the way up in the camera.

The purposely disturbing moments are much more artfully done. Ann and Andy meet the Greedy, a monstrous wad of goop who’s constantly eating himself alive like the Ouroboros. This was Looney Tunes animator Emery Hawkins’ showpiece, and his work is so intricate it’s almost exhausting to watch — put it on in slo-mo if you want to even begin to catch it all. His Greedy is a literally genderfluid character, constantly shifting shape and sex.

In an era when animation was mostly still images moving as little as possible, the best parts of Raggedy Ann never stop moving. And even in the most elaborate hand-drawn animation, the background is almost always static, but Williams is always redrawing it from every imaginable angle to simulate the effect of a live action camera, but unbound from its limitations. The Greedy was a godsend for him, giving him a backdrop without a straight horizon line, so he could move all around without having to worry about questions of perspective. And as if one constantly shifting liquid monster wasn’t difficult enough, Raggedy Ann introduces another in the last act with Gazooks, a sea monster who’s always bubbling and shrinking and swelling like the world’s wateriest water bed, never the same shape in one frame that he was in the last.

This sequence and the dolls’ later trip to Looney Land use a trick Williams carried over from his Pink Panther credits sequences and would use again in Thief. The “background” is nothing but plain black, the better to contrast the detail and bold color of the characters.

It also goes a long way to explaining Raggedy Ann’s oppressively disturbing atmosphere. I don’t remember any of the specific horrors that have stuck in the collective consciousness — the Greedy, those naked dolls, the cackling citizens of Looney Land — scaring me, but I do remember a vague feeling of unease.

This doesn’t mean Raggedy Ann doesn’t create a vivid world. Other scenes feature gorgeously atmospheric watercolor backdrops of the Deep, Deep Woods, apparently enhanced by pinholes that let through real light to simulate the starry sky and multiplane camera effects that allow the characters to move in three dimensions.

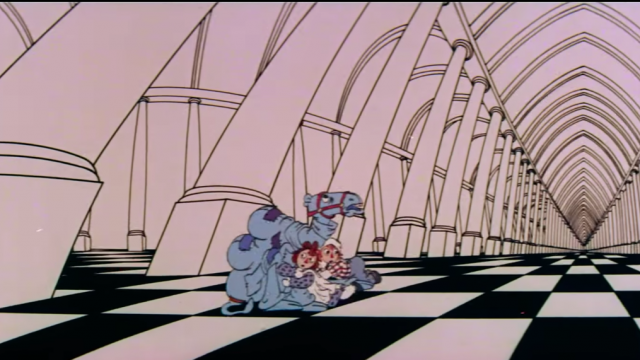

Ann and Andy’s entrance to Looney Land is one of the movie’s most stunning moments. If Williams cheats perspective in the Greedy sequence by forgoing straight lines, he fills the chase through Looney Land with as many as possible. Using tricks he’d recycle for the most famous moment in The Thief and the Cobbler and the opening “Somethin’s Cookin’” sequence of Roger Rabbit, he makes the shifting perspectives as complicated as possible by setting the action on a checker-board tile floor that mesmerizingly warps and straightens, under a vaulted ceiling drawn with diagrammatic precision. Later, the chase takes the dolls down the railing of a spiral staircase that seems to unwind itself as we follow them down.

Looney Land is ruled by the tiny King Koo Koo, who, in an apt metaphor the movie respects its young audience enough not to spell out, needs to laugh at other people to make himself bigger. Even though he and his knight Sir Leonard Looney come from Gruelle’s novel The Camel with the Wrinkled Knees, they seem bizarrely out of place next to the turn-of-the-century timelessness of the main characters. Their wildly stylized and simplified designs and clashing colors — Koo Koo has salmon-pink skin and lime-green hair — couldn’t be more ‘70s. His subjects look like they’d be more at home on Sesame Street or Schoolhouse Rock.

For all the horrors this movie traumatized generations of kids with, Looney Land provides the worst, but also the easiest to miss. When the dolls successfully crack the king up, he announces his plan to imprison them so he can keep growing. Then he threatens that when he gets bored he’ll turn them into “one of them!” pointing at the mindlessly cackling creatures surrounding his throne. In other words, these wacky characters are the result of implied lobotomy, and the heroes are next.

Ann, Andy, and the Camel, eventually escape and find Babette, who’s taken over the pirate ship and, not wanting to go back home, imprisons her “rescuers.” King Koo Koo returns and just in case you think that implies the whole plot has been thought out, it’s not the heroes who defeat him but the Captain’s obnoxious parrot.

In his classic history of animation, Of Mice and Magic, Leonard Maltin says that at the time, “Richard Williams seemed like the likely leader of the industry.” But he comes to a less optimistic conclusion about the animator’s debut feature: “No one could deny that the finished film was well-animated, but it was also slow-moving and surprisingly joyless…The principal emotion expressed in the film is frustration.” That pan could mean a lot of things. Certainly, Ann and Andy’s story arc is mostly about frustration, as they face setback after setback just to find out their help was never wanted to begin with. But it also describes the experience of watching the film itself, seeing flashes of artistic genius occasionally rise out of the morass like the delicacies that pop out of the Greedy’s gloppy body, to see a filmmaker come so close to greatness while being held back at every turn.

A 4K scan of Raggedy Ann and Andy: A Musical Adventure directly from the original film strips is available on YouTube