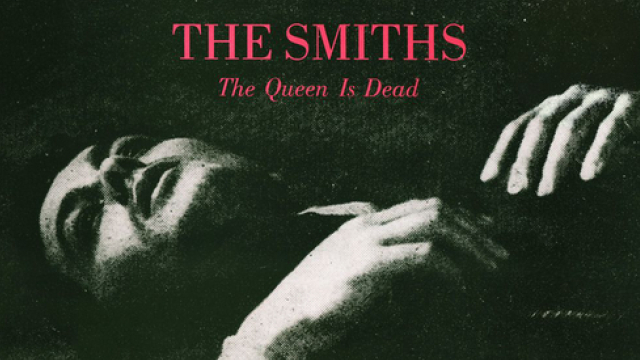

There are many reasons why I myself consider The Queen is Dead to be the Smith’s greatest release beyond simply following the critical consensus like the sheep that I am. It is the most consistent in terms of song quality, with Morrissey’s most confident set of lyrics and vocals and an increasing large sonic palette from Johnny Marr compositions. All stories point to the writing process of this record being quick and spontaneous, thus why it is both a variation of many genres – sixties pop and garage rock, rockabilly, post-punk, ballad and rockabilly – yet still maintains a singular vision (as opposed to Strangeways, Here We Come, but more on that tomorrow).

But this record shares a trait that not many great albums can claim to: it’s funny. Not just amusing, not just nod your head and appreciate the references like the good little intellectual you are (which, let’s be fair, the Smiths could be guilty of), but at points genuinely laugh out loud funny. Be that Morrissey’s casual sarcasm, the contrast between subject matter and the music or just unexpected turns of phrases that catch someone off guard, the wild humour here – both with and without the e – lend both an ease productions and an emphasis on its point of view. This is many ways is just as political as Meat is Murder; I mean, just look at that title, and it was originally going to be called “Margaret on the Guillotine”. Don’t get me wrong, not every track on here is a laugh riot – in fact there are two songs on here that are the Smiths at their most melancholy – but that in turn helps heighten every motion, the same way that every anachronism in music and subject matter helps lend to the album’s still contemporary sound.

Speaking of anachronisms, the title track kicks off with Morrissey against the Royal Family and their “pale descendants.” You can almost hear him joke around in the studio with the way pronounces piannnner or his voice breaks when claiming he “never even knew what drugs were.” But Marr’s composition here allows everyone in the band to have their moment. The way that the song begins with those tribal hits of Joyce’s drums before Marr’s guitar wah’s into the frame, the way that Rourke’s bass adds to the propulsion and harsh sound even when being so high in the mixing, and the way the phasered notes go in and out, pulling back and pushing forward. All of this culminates to the hardest the Smiths have probably ever sounded (next to maybe “The Headmaster’s Ritual” or What Difference Does it Make”), but the clever use of Marr’s trademark jingle jangle towards the end of the track gives it this sarcastic, ceremonial feel.

The ceremony adds to “Frankly, Mr Shankly” and its sense of the music hall. When I hear this song I can imagine in my head the stage it is being played on, though compared to the demo version it is a much smaller venue. While I appreciate the trumpets of that version conceptually, the stripped down sound here really complements Morrissey’s somewhat brutal lyrics said to be against the founder of Rough Trade Records; no authority figure will remain unchallenged. Every instrument on the track is so damn bouncy, particular that bass, the Kink’s like drums and how both guitar sounds complement each other, and all of this adds to the bluntness of Morrissey’s declarations that “Mr. Shankly” writes “such bloody awful poetry.” And even after all these insults, they still want the money! This to me is the funniest Smith’s song that doesn’t go too overboard in the parody area.

Despite everything I’ve said about this record’s humour, here we come to the most forlorn ballad the Smiths ever penned. Just like how “The Queen is Dead” ended with “life is very long when you’re lonely,” in the midst of the glib not allowed to forget the harsh, and the vice versa is also true. Morrissey can feel the soil falling over his head in “I Know it’s Over”, being buried under the weight under his problems, and every accusation of his own hubris and ego is thrown at him with the pondering of why he is so alone if he is so popular. It’s Morrissey at his most country music levels of confessional. People might disagree, but I could imagine song being performed in another 1986 masterpiece, Blue Velvet, mainly down to the smoky bar feel the interplay between the damp bass and the bright guitars give us. That mood is maintained to the next track “Never Had No One Ever,” which also contains some sweeping of synth and flute instruments that lets us know the lushness that is going to come. I have to say that out of process of elimination I would probably call this the weakest track on the album, if only due to it feeling as long as the previous track despite its shorter length. But the varied guitar sounds from Marr and the way Morrissey contrasts his loneliness both towards a whole city and towards a singular person.

Not to threat though, the end of Side A returns with the funny, and the spell checker hell that is “Cemetry Gates.” In many ways this whole song is the biggest celebration pisstake on the English language: Keats and Yeats look like they should rhyme but they just don’t, and he claims not to plagiarise whilst taking whole chunks of dialogue from plays and books. All this adds to one of the cleverest come backs to “big nose” critics I’ve heard; normally no artist looks good attacking their critics, because they sound so bitter that it doesn’t amount to anything, but here the song is just too playful for anyone to hate. Much that can also be down to Marr, with a riff that he was convinced sounded incomplete. Thank goodness his mind was changed, because this riff is so bright and joyess, with an almost Celtic vibe that one could skip to without any shame. Though as leaders of the Rourke and Joyce Fan Club we should acknowledge how they mask any ideas of incompleteness by filling up the sound, be that Rourke’s bass intro or Joyce’s constant high hats.

I wish I had time to record things for these articles, because “Bigmouth Strikes Again” used to be my go to talent-show contest song (2nd place biatches!). It’s initial riff is so simple – its main difficult being speed – but from that riff births every great accompaniments. From the rolls of Joyce’s snare and cymbals, Rourke’s perfect bass blips and the inclusion of both synth fills and manipulated voices. All this elevates Morrissey’s position as the aforementioned Bigmouth of the track, a martyr against the record industry – though vague enough to be about anyone really – with anachronisms both intentional and unfortunately a product of the passage of time (last I heard Morrissey changes that “Walkman” to an “iPod” now).

That attitude of The Smiths biting the musical hand that feeds them moves on to “The Boy with the Thorn in His Side” (the single branding the best photo of Truman Capote). On each album there is at least one single that predates the sound that is to come for the next. For The Smiths that is “Still Ill,” for Meat is Murder it’s “Nowhere Fast,” and the sound for Strangeways, Here we Come can be found on this song. Marr’s trademark bright guitars can be found on here, but the song’s most noticeable stylistic choice – at least compared to the single version – are the lush use of synthesised strings permeating the whole thing. The Smiths have used other instruments for accompaniment since the very first single and album, but here is the first time I would consider it the main trait of the track. But they just work, especially when crossed with one of Morrissey’s best vocals; this song is so bright it almost coaxes him out of his dour shell (don’t worry, his love still contains a “murderous desire”).

Next comes “Vicar in a Tutu,” a song I really like, although I appreciate the live recordings more; for some reason Morrissey’s voice is a bit echo-y (perhaps to give the idea he’s in a church singing this?). The skiffle/rockability nature of Joyce’s drum and Marr’s guitar licks (Rourke’s bass serves more to enhance the sound here) are as wonderful a contrast as the central image, as Morrissey tackles probably the final authority figure he has yet to touch: organised religion. With criticisms of the dogmatic naïve nature of the church, as well as criticises the for-profit nature of the services, Morrissey manages to do all this without ever ridiculing people with faith – I believe he’s deist himself; go figure – and with the joyful beat the only people who chould criticise its message are probably the ones that deserve the ire.

We now come to the climax – though not its conclusion – with what is probably the most famous song of The Smith’s canon. It’s had book chapters dedicated to it, crucial scenes in movies revolving around it, and many a bar play and drunk karaoke cover. One can’t deny the severe exposure of “There is a Light That Never Goes,” and yet that still hasn’t made this rebel without a cause anthem less impactful (to me anyway). If “This Charming Man” was the quintessential sound of the first two records, this is for the final two. It is all there, the bright major chords contrasted with the aforementioned melancholy of Morrissey’s ambiguous lyrics (that despite its suicidal subject matter I still find parts humorous, though maybe I’m just a sick person), with a marvellous rhythm driven by the precision bass of Andy Rourke and the energy from Mike Joyce’s toms, and an amazing backing of synths and flutes that wouldn’t sound out of place in an Orchestra. Something so dark. Something so happy. Something so Smiths.

This would have probably been the most climatic ending The Queen is Dead could have had, but instead the album ends with the Carry On stylings of “Some Girls are Bigger than Others,” which begins with a sound dip that I imagine has made many people rush to their speakers. Possibly an overreaction to the responses from “Meat is Murder,” this has gone from the absolute preachy to the absolute farce. I kind of agree with Simon Goddard when he says that to put those lyrics with one of Marr’s best riff – and it is one of his best, close in my mind to “Still Ill – is almost sacrilegious. And yet, I don’t think I would have it any other way. The Smiths would later go on to self-parody their own self-parody, but here it fits and creates the ending that sums up the record as opposed to the songs; both shallow and profound (better stop before I go full on Mystery Men).

The Queen is Dead is everything I love about the Smiths: funny, melancholic, bright, musically complicated, catchy, unafraid to make fun of or comment on anything, including themselves. If there was one record that I had to recommend to anyone to get a sense of who the band are, it would be this one.

With this record they were on top of the game. They could have gone for so much longer. Sadly, due to stress and band tension, they wouldn’t. There would only be one more. But it would sure be an interesting one.

What did you think of the album, though?

The Smiths Album Rankings

- The Queen is Dead

- Meat is Muder

- The Smiths