Famously, only two original songs were written for Singin’ in the Rain, both of them designed to show off Donald O’Connor’s showmanship: “Make ’Em Laugh” and “Moses Supposes.”

“Make ’em Laugh” is a pretty straightforward love letter to vaudeville and the circus arts. “Moses” is a little more complicated.

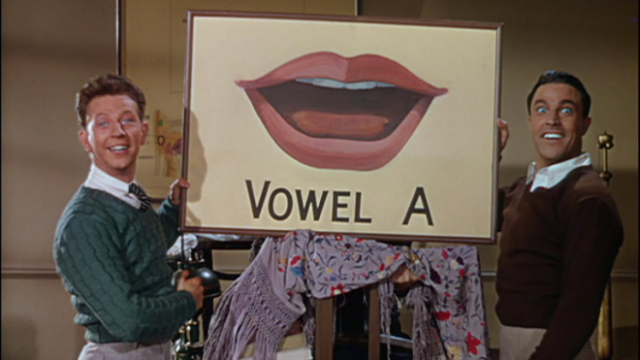

“Moses Supposes” starts in a diction coach’s office, as Gene Kelly works to make his voice talkie-friendly (of course, he already sounds just fine, but let’s not let that get in the way of the fun). Donald O’Connor’s Cosmo takes the coach as seriously as the work deserves, and the voice lessons deteriorate into a chaotic, jubilant dance number, ending with the poor coach wholly invisible, covered in the contents of his office.

The song is, at its core, a goof, a children’s rhyme turned into a flashy dance routine. But it’s also an anarchic statement against the very forces that challenged the movies in the transition to “talkies”: (and, in many ways, still persist); the desire to have everyone sound near-identical, the flattening of regional accents and identity in place of a common, dull, consistency.

One of the interesting details of this scene are the many elements you might expect in a speech therapist’s office of the time, and might see even now. Big posters showing off what the vowel sounds were supposed to look like, a medical diagram of the throat and vocal chords. Almost every accessory in the room — most of which the hapless vocal coach ends up wearing — relate to the work being done; the curtains that get “worn” like robes are the biggest exception. (The set design, like everything else in this movie, is really stellar.)

There’s a tension in work that’s meant to correct speech. (Speech therapists, more accurately called speech language pathologists or SLPs, treat a variety of issues, not all of which are related to speech clarity. There are also diction and vocal coaches. I’m not sure how Bobby Watson’s character would have been educated; the lines can be a bit blurry and have changed over time.) On one hand, it’s important for people to know what you’re saying. On the other, the mere presence of an accent is usually not enough to make people incomprehensible, and the kinds of “speech” that are considered “clear” are subject to cultural forces.

For many years, commercial radio and television was infamously dominated by the “mid-Atlantic accent,” and anything else was deemed unacceptable. In his memoir, Desi Arnaz talks about the hours he spent trying to get rid of — or at least lessen — his distinctive Cuban accent, to very little success. In contrast, National Public Radio encourages their hosts to keep their natural accents, which means a listener over the years could be treated to the Romanian musicality of Andrei Codrescu or the strangely catastrophic tones of Sylvia Poggioli. (Seriously, every story she files sounds like a crisis.) It’s clear that people can understand unusual accents, but many commercial productions work to strip every ounce of friction out of a listener’s experience.

Rather obviously, the mid-Atlantic accent is not Jewish, Italian, or Black. It covers itself in whiteness to be registered by the listener as bland and featureless — “normal.” After the talkies started, entertainment started on a path toward sameness that it still hasn’t shaken. There were, and continued to be, exceptions. English actors have always sounded “classy,” Tony Randall and Orson Welles got to show off their spectacular elocution, and America really did grow to love Desi Arnaz; but the “acceptable” accents were few and far between, and connected to wealth and class. (Think of “I don’t know nothin’ ’bout birthin’ no babies,” or the distinctive rasp of Peter Lorre and how easily it was mentally associated with criminality. Don’t even get me started on Bela Lugosi.)

I don’t think the makers of Singin’ in the Rain thought about this too much — after all, the plot turns on the main adversary having a heavily-accented, absolutely grating voice — but it’s hard to miss the subtext if you’re looking for it. By the time the poor speech therapist is piled with posters, the sheer joy of the performance has you cheering Kelly and O’Connor on.

Kurt Vonnegut’s eight rules for fiction, ones I’ve always held close to my heart, say “Every sentence must do one of two things — reveal character or advance the action.” I’m not actually sure “Moses Supposes” reaches that lofty goal; both character and action could have been taken care of in a scene half the size, or shorter. But this goofy riff on a nursery rhyme is just the right length; the choreography is jubilant, the lyrics effortlessly ridiculous, and the performers give their all.

Even after all these years, “Moses Supposes” is still a fun, anarchic stick in the eye to respectability and “class,” and probably the scene I revisit the most. (It’s also a hell of a lot of fun to sing along to, after all.)

Final notes:

Of course, I had to include this delightful anime tribute to “Moses Supposes” and Singin’ in the Rain.

Want to know more about the intersection between race and ‘acceptable’ dialects? This New York Times article is a good place to start.