Hitman’s balance of the silly and the deadly serious tipped more towards comedy in the first third of its run, but shit starts getting real around the time of Who Dares Wins. McCrea keeps right up with Ennis, as his artwork becomes steadily more realistic from here to the end of the series, with some images giving his characters all the detail and expressiveness of live actors.

The bill finally comes due for Tommy and Natt’s friendly fire incident, and it’s a hefty one. The bodies emerge out of the desert sands, and the terrifyingly skilled men of the British Special Air Service come to Gotham to take Tommy and Natt out.

Ennis has always been fascinated with the world of military professionals. All of his antiheroes — Tommy, Natt, Noonan, Ringo — got into the game because they served in the military and had no other skills they could apply to civilian life (except for Hacken, who got his Gulf War shirt with a video game), and we see flashbacks to all their time in combat.

But Who Dares Wins finally gives him the chance to tell a full-blown war story in these pages. These one-off antagonists in the SAS Squad get more depth than most comics give their heroes. We see the camaraderie, their love expressed in meanness, not unlike Tommy and the boys at Noonan’s Bar. But when the time comes to go to work, they’re frighteningly no-nonsense. As a character in Ennis’s Punisher says, the mob can give any man a gun and call him a “soldier,” but the real thing is something else entirely.

There’s an odd contradiction here. Ennis’s love for the fighting men doesn’t extend to the causes they fight for: he’s one of the most clear-eyed writers in comics about the horrors of geopolitics, even if he exaggerates it to comic book levels with characters like Truman. We’re introduced to the SAS squad executing Irish freedom fighters, participating in the Troubles that upended Ennis’s Northern Irish youth (for the record, his Punisher story Kitchen Irish makes it plain he hates the IRA). Later, Tommy meets an Airborne officer who reminisces on the Falkland Islands War in the midst of a story that’s deeply cynical about Western powers’ interference in other countries’ affairs. It’s a paradox that would take a far more skilled critic than me to untangle.

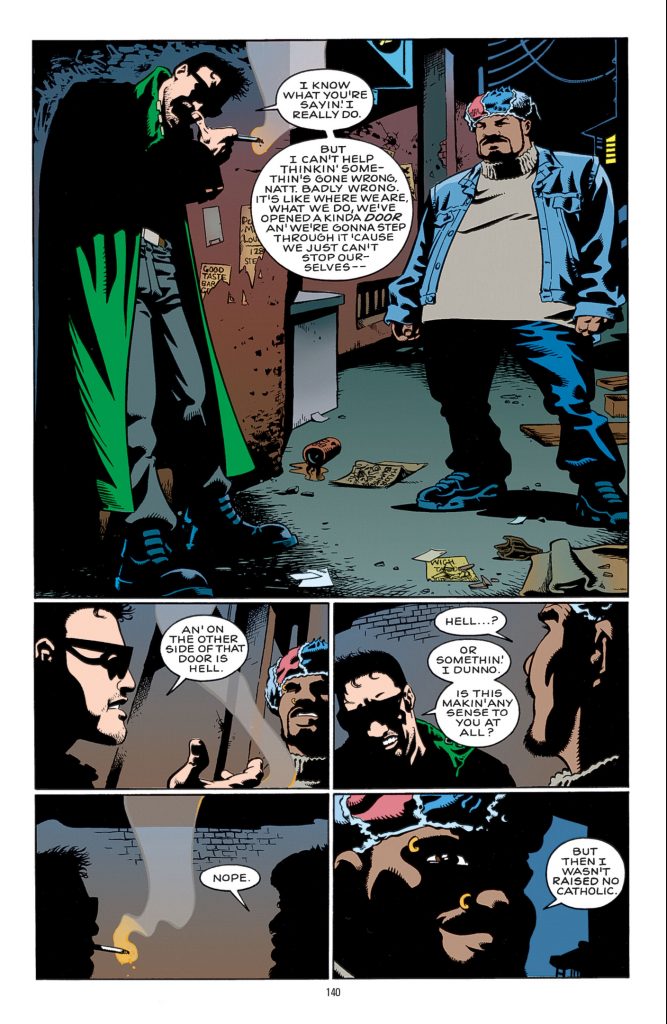

Against the SAS Squad’s precision, Tommy and Natt’s only weapon is total chaos, which they unleash by blowing up their vendetta with Men’s Room Louie and hoping the squad gets caught in the middle. It works, but only barely, and the price is high. Tommy and Natt fall into a depressive funk after facing death more closely than even they ever have. Tommy comes to a realization that will shape the rest of the series (even if it loses some impact in a comic that had already featured a very literal, cartoonish version of hell):

That guilt’s at least part of what leads the cast overseas in Tommy’s Heroes. This is where Ennis’s geopolitical cynicism comes in. An NGO called Third World Concern drops by the Cauldron to solicit Tommy, Natt, and Ringo (Hacken tags along too) to train soldiers in the African nation of Tynanda to fight drug-dealing rebels. There’s already a note of commentary there — after all, what’s really the difference between military contractors and contract killers? As the story goes on, we learn Third World Concern are really heartless capitalists fobbing off weapons on Tynanda they can’t sell anywhere else, and the Tynandan military, even the “superheroes” Tommy serves alongside, are baby-murdering bastards propped up by foreign influence.

But Ennis isn’t willing to take his anti-imperialist stance all the way to the end. Tommy and co. meet up with the rebel general Christian Ributu, and even though they had just been suckered by one leader, they decide he’s the good guy after knowing him all of a couple hours and help him take the capital. Whether by the demands of narrative or the limits of Ennis’s vision, Tommy’s Heroes ends up as an example of the same White Savior narrative it skewers.

Then again, who needs social consciousness when the carnage is this spectacular?

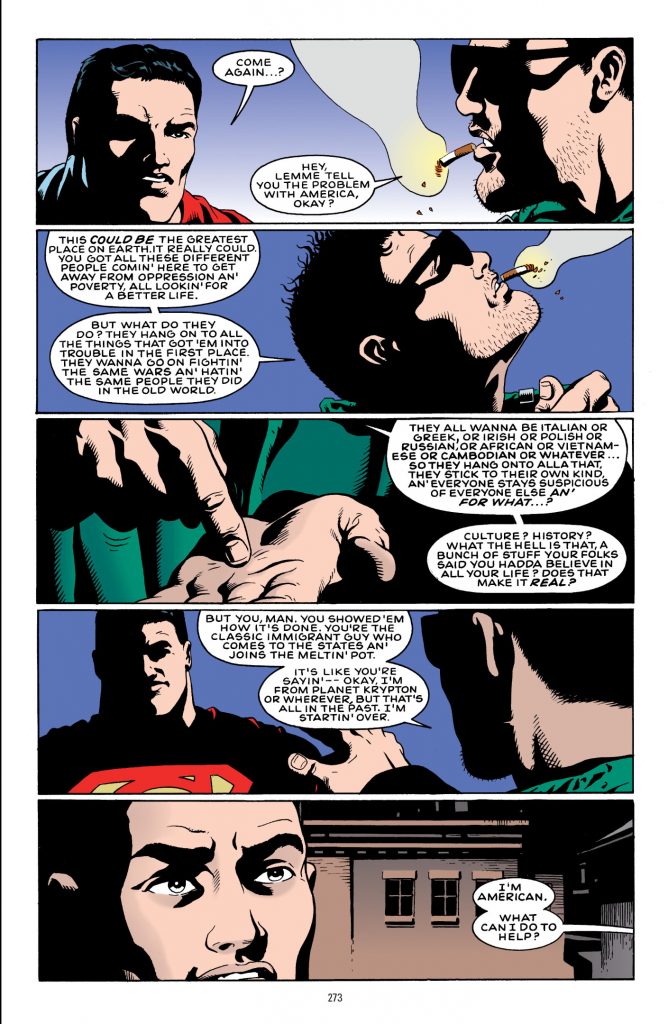

After that’s two of Hitman’s most iconic moments. First, in, “Of Thee I Sing,” Tommy meets Superman. Ennis has a great ear for the hero’s voice and internal struggles, but I’m not as high on it as a lot of fans. The novelty of such a cynical superhero-hater treating Big Blue so reverently may go further than the actual quality of the writing, and Ennis’s turn to sincere inspirationalism is uncomfortably assimilationist:

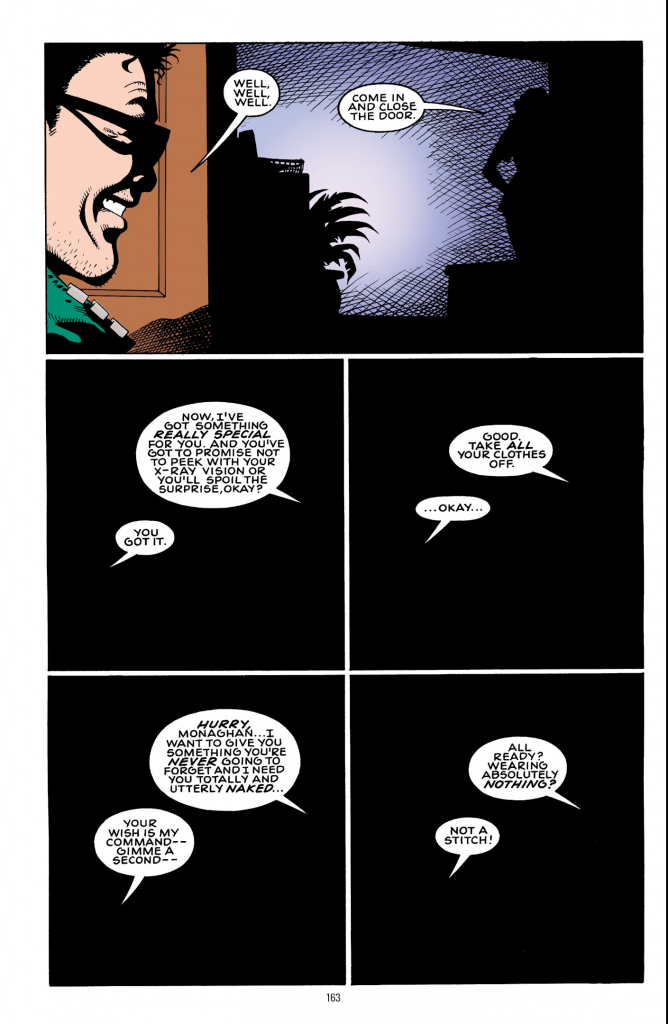

But I don’t have any of those qualms about Hitman’s intrusion into the DC One Million crossover. Don’t try to make too much sense of how the plot, where Tommy’s become a mythological hero for fighting the evil Batman, fits in with the main story, where Batman himself is a mythological hero. Better just to enjoy the hilarious pettiness of Ennis’s victory lap around Gunfire, the only other Bloodlines character to get a spinoff, who’s seen here turning his ass into a hand grenade after Hitman finally outlasted him.

After a trip back to the Old Country and a fight with some Anne Rice-parodying vampires, setting the cycle of tragedy-comedy-tragedy the rest of the book would follow, Hitman settles in for its last two years fatalistically proceeding to its final chapter, as the characters’ lives of violence catch up with them one by one.

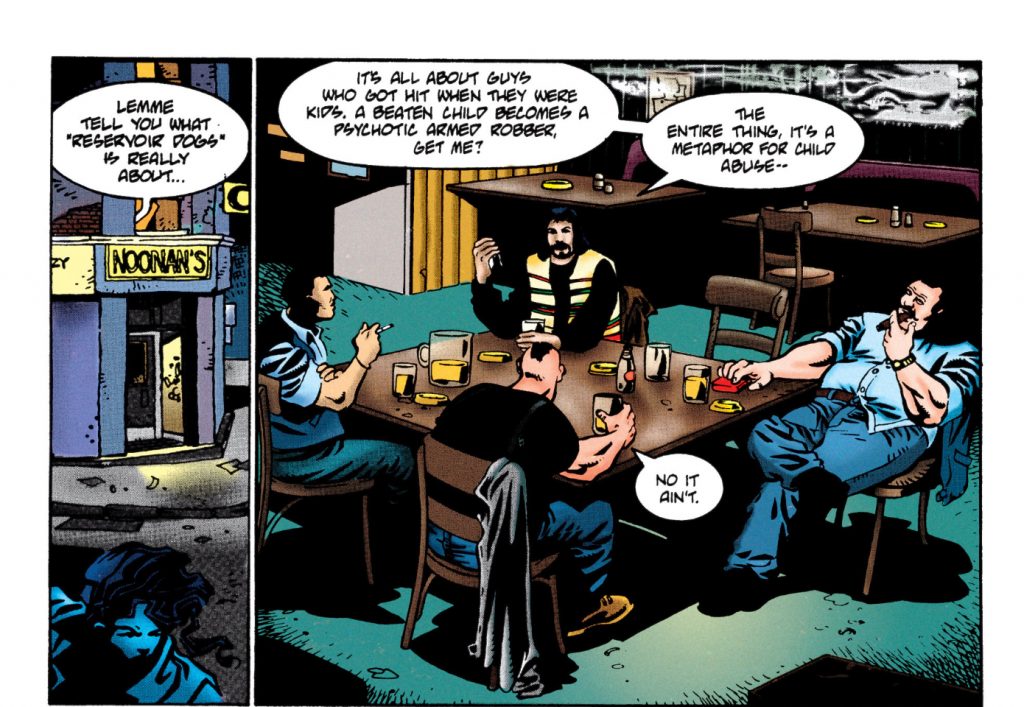

First to go is Ringo Chen. With his disdain for superhero comics, Ennis looks for most of his influences in film. The many scenes where he just lets his characters talk, often about pop culture trash, in between gory shootouts, has a lot to do with Tarantino, who Ennis references in one hilarious early scene by rewriting the “Like a Virgin” monologue from Reservoir Dogs to be about Reservoir Dogs.

Noonan’s Sleazy Bar sits on the corner of Peckinpah and Saint, evoking the great filmmaker to intimate the series’ precarious position between spiritual concerns and nihilistic ultraviolence. And Ringo’s swan song, For Tomorrow, gets a name evoking John Woo and Chow Yun-Fat’s A Better Tomorrow, and the director and star get a dedication in its final panel. It makes sense — the one’s love of impossible stunts and all things over-the-top is felt throughout the series, and the other’s ice-cold stylishness is the prototype for Ringo.

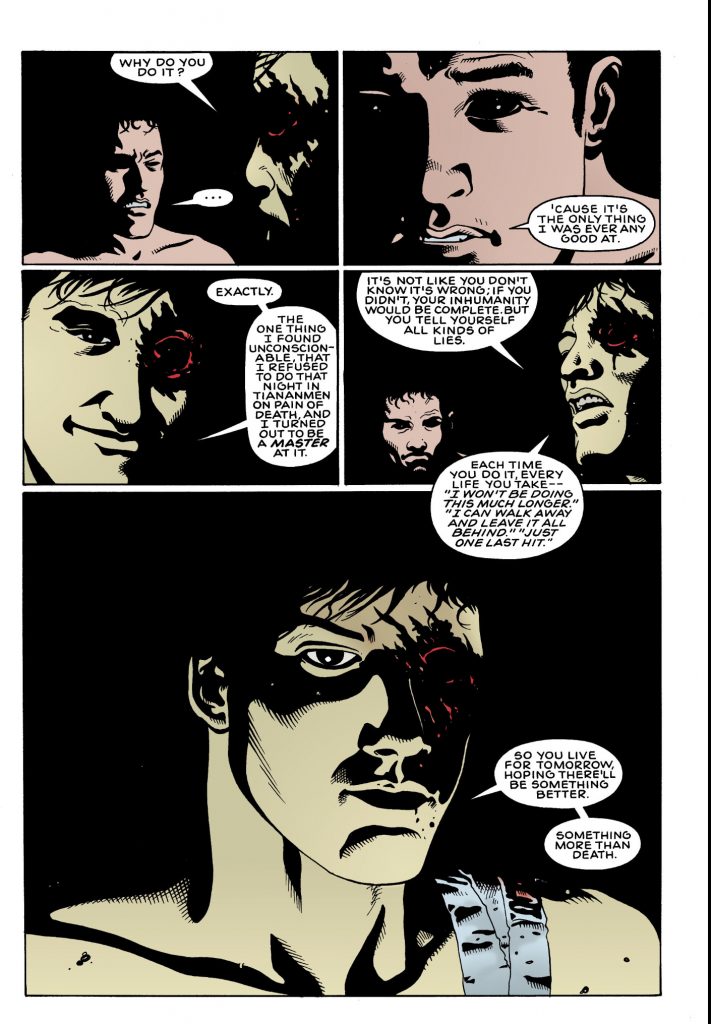

That title has a deeper meaning too, turning the old cliché of the one last job into hardboiled philosophy. Ringo explains,

Ennis is wrestling with the morality of his premise again. But the assassins’ sins mean it’s not as easy as all that, and Ringo dies in revenge for the murder he commits the same day he decides to get out. But he gets revenge of his own.

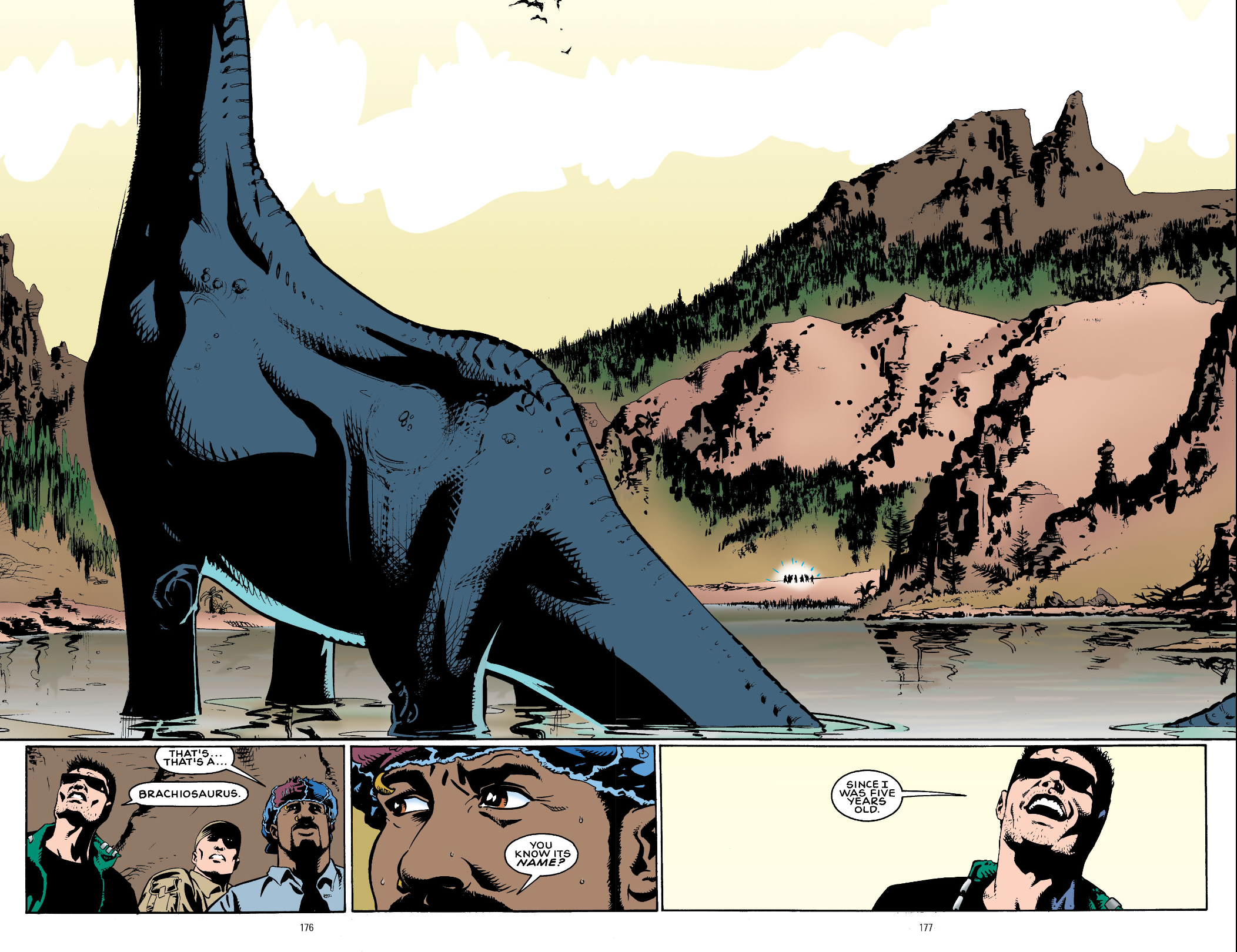

After all that heavy stuff, Ennis and McCrea give us a breather with another wacky comic booky story with that four-color standby, the dinosaur. This time, thanks to Injun Peak and a big game hunter with more money than sense, a horde of dinosaurs are unleashed on the Cauldron, and…well, just take a look:

In between all the zaniness, it’s also an unusually clear view into Ennis’s psyche. We get to see Tommy’s softer side in his awe of the dinosaurs:

And in the end, they condemn the soulless, polluted modern world and return to their own time. But Ennis introduces us to that idyllic past with violent macho dominance undiluted by any higher goals as T-Rex Scarback eviscerates another dinosaur for challenging him. Not exactly a better alternative, near as I can see.

Tommy also learns the hard way what happens when you cheat on a zookeeper:

Next to go is Sean. He and Tommy have been drifting apart over the past year over Tommy’s discovery Noonan had hidden the truth about his father. But in some of the book’s most powerful moments, Ennis explores what fatherhood really means.

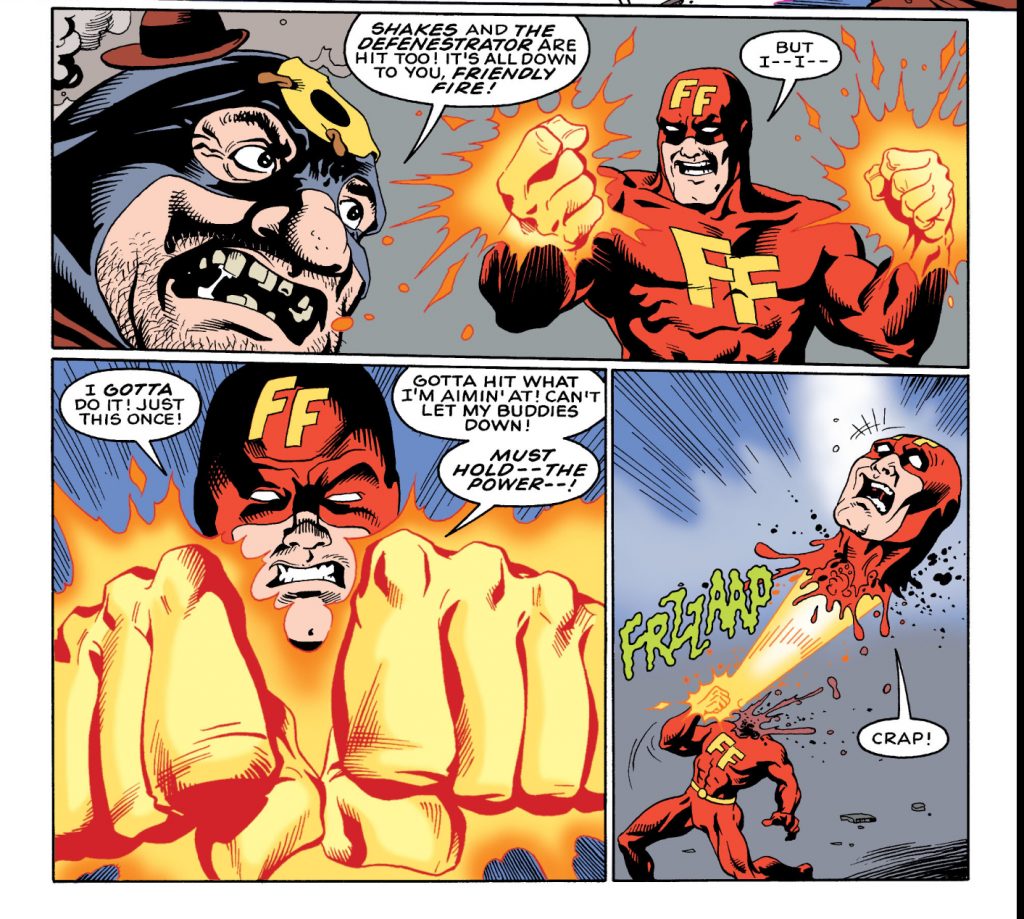

Even Sixpack gets a tearful sendoff in Superguy. We get to see him and his ridiculous “superheroes” at one of their weekly meetings, and Ennis and McCrea make Friendly Fire’s mockery of the whole thing hit your funny bone one moment and come down like a ton of bricks the next.

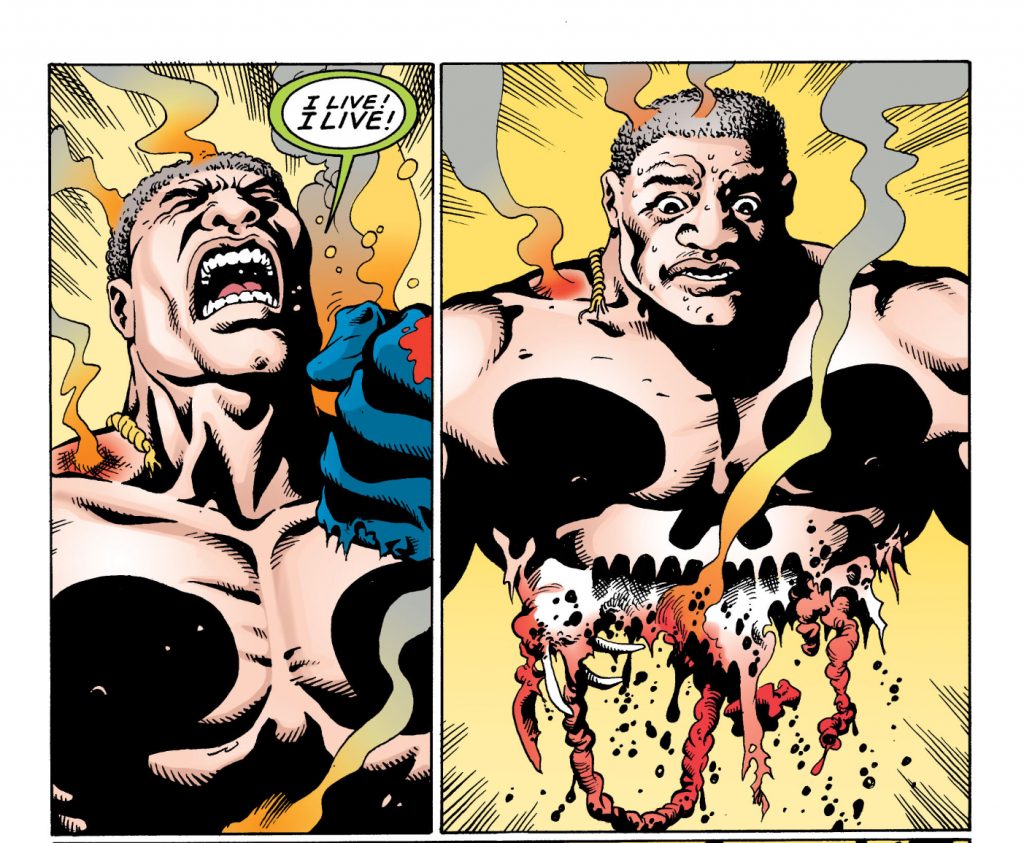

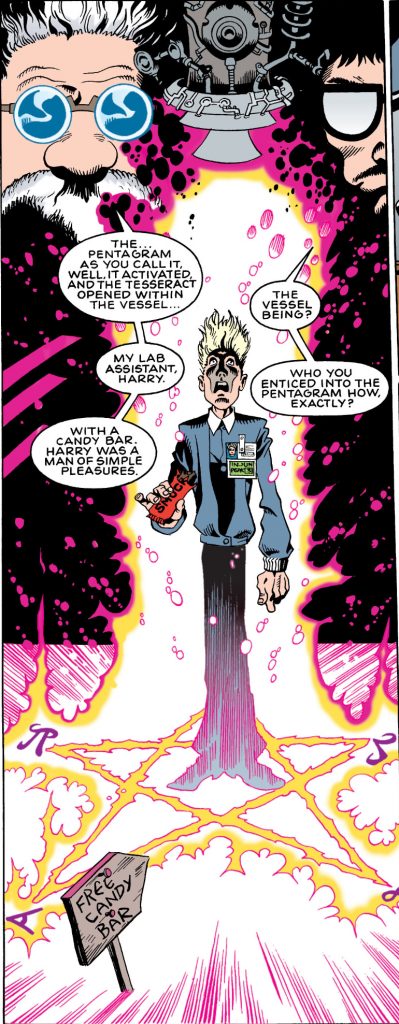

Superguy is also the apotheosis of Hitman’s absurdity, pitting Natt and Tommy against a man who can literally pull anything out of his ass, who gained his power in the wackiest way possible.

It’s the best example of Hitman’s balancing act. The demons Professor Haddock summoned take out Section Eight, including one of the greatest death scenes in a series with no shortage of great death scenes.

But when the time comes, Sixpack proves he’s not just delusional. He really does get to be a hero, and that, more than Hitman’s meeting with Superman, is when Ennis’s anti-super cynicism falls away the most movingly.

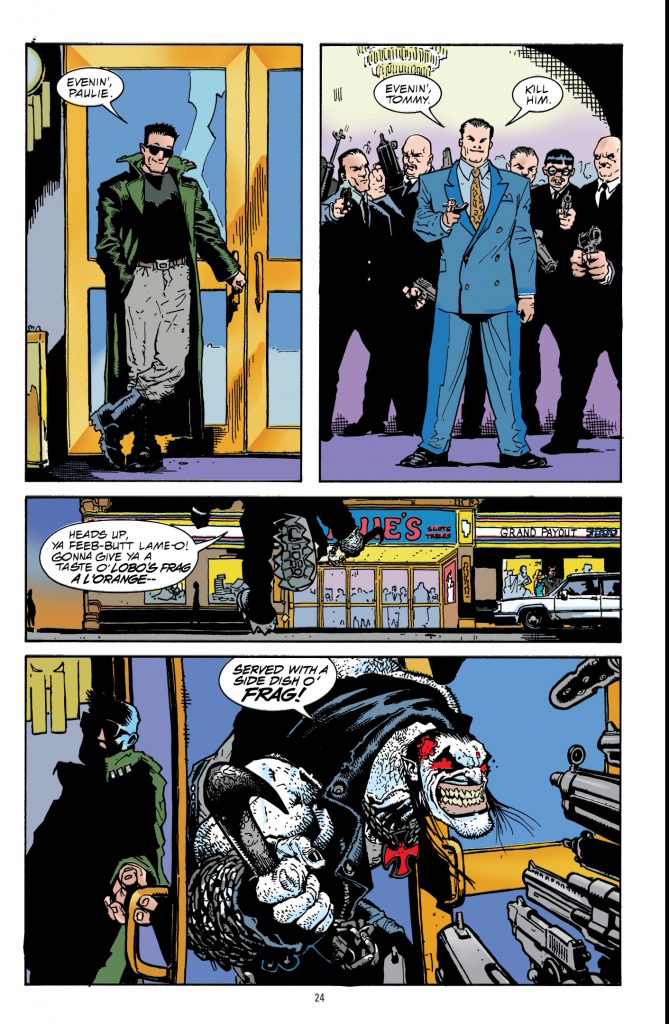

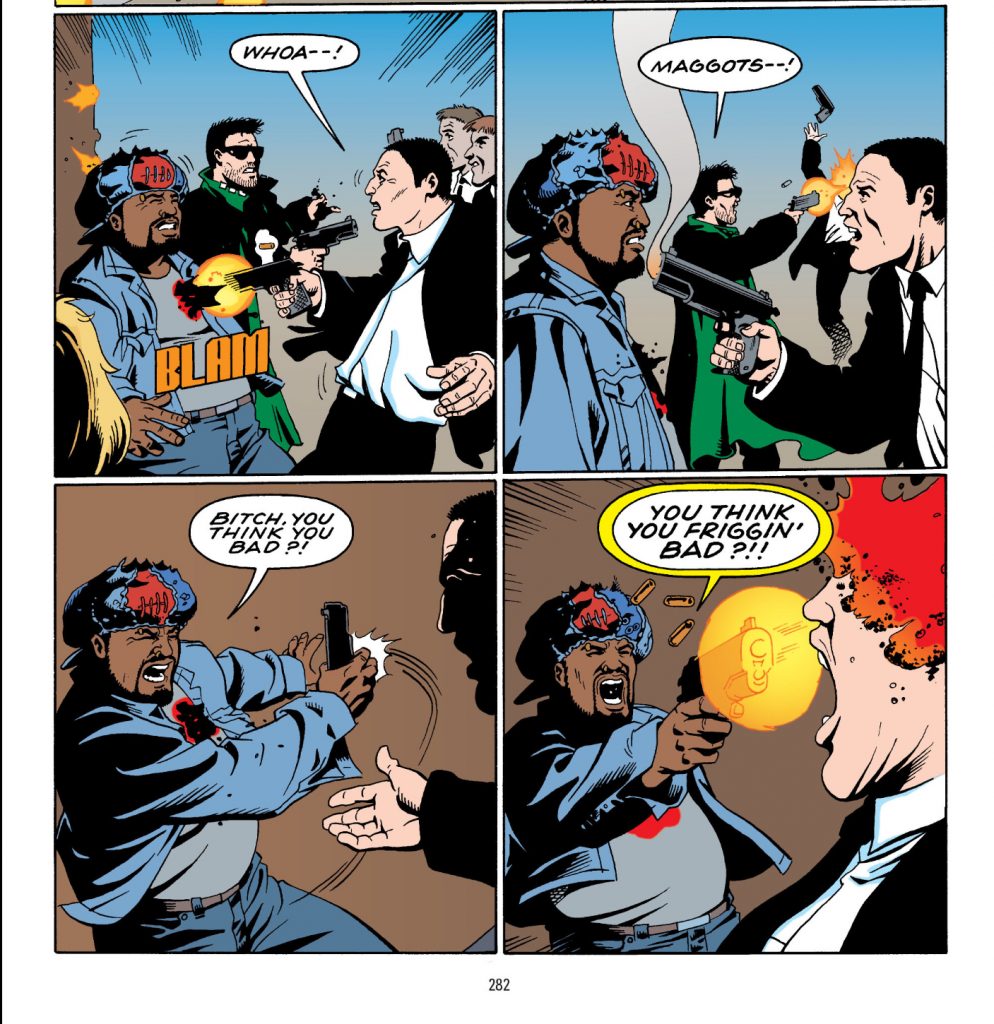

Back to the cynicism, the Hitman/Lobo special gives Section 8 one last bow (or, in Ennis’s words, “This story takes place before certain members of the cast were slaughtered”) fighting against the DC Universe’s space bounty hunter. It’s easy to see why someone might think they’re a natural pairing — two scummy super-antiheroes with no compunctions about killing. Thing is, Ennis hated Lobo. Tommy might kill people for a living, but Lobo was something much worse, a swaggering self-important bully. And as you might guess from his politics, Ennis has no time for bullies. So “That Stupid Bastich” sees him take the so-called Main Man down several dozen pegs, with some help from Doug Mahnke, whose art, much more detailed and tactile than McCrea’s, really brings home the barrage of cartoon violence, and he gives the two principals body language worthy of Bugs Bunny and Yosemite Sam.

And then there were three. Tommy, Natt, and Hacken. The mood is already elegiac in the epilogue to The Old Dog, which flashes forward fifty years, after Hitman’s cast are long dead and passed into legend. Closing Time, Tommy’s final story (give or take a followup crossover with the JLA) opens with a haunting image of every major character who’d died up to that point as Tommy describes a dream where they welcome him to a drinking party somewhere beyond the grave.

Closing Time weaves together threads from the very beginning of Hitman’s career. Johnny Navarone is back, or at least his son is (why they’re apparently the same age is never explained). So is Truman, and his plan to create his own superheroes goes all the way back to Tommy’s origins, using DNA from the aliens that gave Tommy his powers.

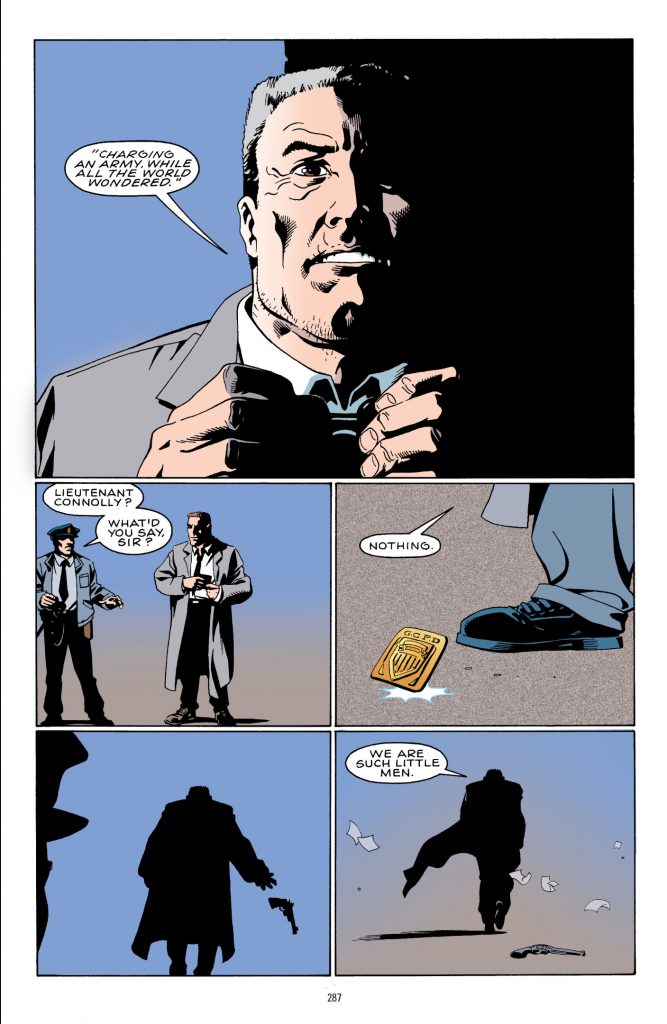

Over the six years of his short life, we’ve been wondering if Tommy can be more than a vicious thug. A cop named Connolly doesn’t believe it, so he halfheartedly fulfills his promise to Noonan to protect Tommy by locking him in a room where the Feds can’t find him. Tommy proves his worth at the cost of his life. A young woman named Maggie Lorenzo comes to him after she witnesses one of Truman’s experiments escape and eat a man alive. The CIA descends on the Cauldron, and Tommy takes them all on to save Maggie’s life.

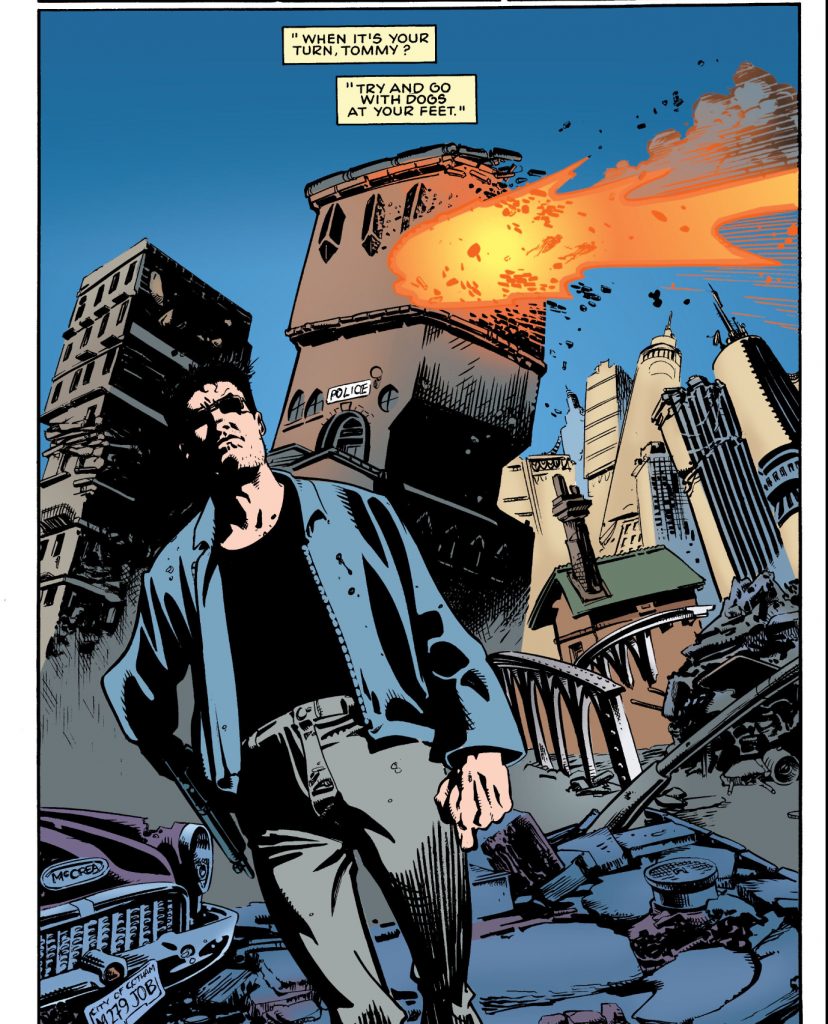

He almost makes it out alive, even though a sniper shot to his hand means he’ll never kill again. But that would mean leaving his brother behind. One of Truman’s goons has shot Natt, and even though he improbably survives with one of the most crystallized moments of ownage in the series

he’s still too badly wounded to make it to the helicopter in time. Natt and Tommy have already seen the horrors Truman is capable of. Letting Truman take his friend alive, however barely, is too horrible to even think about, and Tommy doesn’t take the time to think about it. As he jumps into a hail of bullets, he fires one shot between Truman’s eyes. In most comics, this would be the climax, but here it’s an afterthought, a tiny panel at the bottom of the page. It’s more important for Tommy to kill the man he loves than the man he hates. As he knows he will, he dies in the process. With dogs at his feet.

Even Connolly is awed by the antihero’s final moment of heroism.

Killing Tommy may have been a pragmatic choice to keep him out of other writers’ hands — the perils of working in a shared universe. But it’s also the only way his story could have honestly ended. And it’s such a powerfully moving story, it makes you question the whole idea of these decades-long open-ended epics.

Most writers couldn’t give their heroes a sendoff as powerful as Ennis did, of course. But he got to end the story on his own terms, with a death that still hasn’t been undone. Tommy, the killer who died to keep his code, would approve.