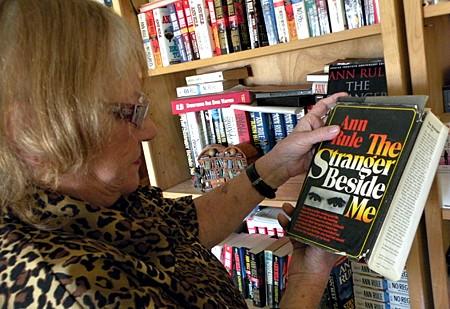

True crime writing does not begin with Ann Rule. Joseph Wambaugh published The Onion Field while Rule was still scraping out a living as “Andy Stack,” writing short pieces. Specifically, for True Detective Magazine, a pulp which managed to last until the ’90s and which started being publishhed seven years before Rule was born as Ann Rae Stackhouse in Lowell, Michigan. The origins of the genre are fascinating and considerably deeper than we’ll get into here. However, starting with her 1980 book The Stranger Beside Me, she was the most notable person working in the field; she spawned many, many imitators and arguably is responsible for the long-lasting pop culture phenomenon of Ted Bundy.

While Rule’s father, Chester R. Stackhouse, was a football coach you might have heard of if you’re familiar with mid-twentieth century football coaches, quite a lot of the rest of her family was in law enforcement. She had relatives who were sheriffs, a medical examiner, and a prosecutor. She spent some time as a policewoman in Seattle. She was, when her career took off, a single mother of four; her ex-husband’s death is mentioned in her first book, which starts shortly after her divorce.

It is of course impossible to say what would have happened to Rule’s career if she hadn’t volunteered at a Seattle suicide crisis line back in the ’70s. She wrote several books after that first one under her pen name, but it was the first one, published under her own name, that really created her career. She’s quite clear in the book that she had the contract before the crimes were solved. Indeed, she seems to have mentioned it, at least in passing, to the guy she spent all those hours of the night with who would tie so intimately into her career.

There is a fairly cruel take on her that she worked to maintain her relationship with Bundy because of her contract. However, I don’t think that’s true. I think it is in no small part because of the horrible guilt she felt at having been one of the people who reported Bundy as a possible suspect in the murders in the Pacific Northwest. Her call arguably didn’t change much—after all, Bundy never was arrested for the crimes he eventually admitted to committing in the area. But part of how she processed her feelings about Bundy was, yes, by sending him money. And if that isn’t exactly the height of journalistic integrity, well, it’s a hard situation to cope with.

What I think her relationship with Bundy did in the long term, besides realistically launching her career, was give her a different perspective on the genre. She’s certainly not the first person from a law enforcement background to be successful at true crime. But what she did was put a different perspective on it. Yes, she told you about the criminal—especially with Bundy. It’s also the book where she told you the most about herself. And she told you about the people trying to catch him, and the later murderers she’d write about. But what Rule tended to focus on more than other writers was the victims.

This is especially notable in Green River, Running Red, a book she wrote after a very long wait for the killer to be caught. Yet for much of the book, the killer is nameless. He’s there, and a little of his story is told, but despite the sheer number of victims, it’s clear Rule is trying to give a page or two at least to all of them. She’s trying to make us see them as people. These are women who were treated as disposable not just by their killer but by the press after their deaths, and Rule is working to rectify that.

Where Rule really revolutionized the industry was by treating victims as people. Oh, sure, Wambaugh did that in The Onion Field—but the victims in that were cops. In his book The Blooding, about the first case solved by DNA evidence, the victims—a pair of teenage girls—are ciphers, and their families are not given much more weight than that. I’ve read a lot of true crime, and no one puts more emphasis on the victims than Rule.

This is the writing I do to help support my family; consider supporting my Patreon or Ko-fi!