The Mission: Impossible series may be at seven movies now and counting, with each installment offering bigger and braver set pieces, but the franchise has relatively modest origins. Instead of a plane to cling to or a skyscraper to scale, the first movie begins with a man watching a bulky CRT monitor in Kiev. On the screen, a panicky man in a stained undershirt speaks to an older, mustachioed guy who could be a former military man. On the bed, we see a woman in lingerie, apparently dead. But as the scene continues, it becomes clear the man is a mark, the woman is fine, and the technician is hunting for a name. Once they get it, their target is poisoned, and the walls of the apparent hotel room fall away, as does the older man’s face. Meet Ethan Hunt and his Impossible Mission Force, although with the amount of stagecraft on display, you’d be forgiven for assuming they were a film crew instead.

While that scene may play out again in Mission: Impossible – Fallout, the stakes here are considerably lower than three nuclear bombs going off. Instead, what everyone’s after here is a list of undercover spies. Following the reliably thrilling opening montage, set to Lalo Schifrin’s iconic theme, we continue the motif of characters watching movies as we meet Jim Phelps on a flight to Prague. The task set forth for his crew involves infiltrating a nameless embassy. From there, they must find a diplomatic attaché who wishes to sell the list to the highest bidder and follow and arrest both him and his buyer. As Phelps, played by Jon Voight says, it’s a “very simple objective.” But as we soon learn, things are rarely simple or what they seem in the realm of espionage.

To say things go wrong is an understatement. The initial crew, which includes Kristin Scott Thomas’ Sarah Davies or Emilio Estevez’s Benji prototype, all go down in gruesome ways. Their mark and Sarah are both stabbed and left for dead, while Estevez’s computer geek Jack Harmon is gored by an elevator prong. Another operative is killed by a car bomb, while Phelps is shot and falls into the Vltava river. Eventually, Hunt is the apparent sole survivor of the mission, going off to phone a friend. He gets directed to a meeting at a seafood restaurant, enclosed in glass, where he meets IMF Director Eugene Kittridge for an apparent briefing and extraction to the United States. However, fish aren’t the only things getting grilled at this establishment, and the apparent transparency of the building is a ruse.

The mission his team was sent on was a “mole hunt,” we discover, with the real list safely sealed away at the CIA. Turns out Hunt and his former crew aren’t the only ones who wear masks, since Kittridge, a spy hunter and excellent foil to Hunt played by Henry Czerny, suspects Hunt is the mole. So begins another familiar signpost for this franchise: the moment when Hunt is cut off from support and suspected of being a traitor. So, in the spirit of clearing the air with Kittridge, Cruise blows a hole in a nearby aquarium and flees the scene, suspecting something fishy going on.

After escaping from his would-be captors, what does our hero, who will in later installments undertake a HALO jump and scale a cliff or two do next? Why, head to a computer, of course, to send some emails and then fall asleep. While later films in the series live up to the usual expectations of summer movies, working hard to bust your blocks off, this first film operates in a quieter gear. Witness, for example, how much time the movie spends with Cruise’s first team, and his interactions with them. Sure, our star may have received a heroic push in from the camera at the beginning as he tore that mask off. But in the Prague briefing room, he’s just one of the guys, making jokes at his boss’s expense, part of a cohesive unit. No wonder he appears heartbroken when he first meets Kittridge. This wasn’t just a group of coworkers but friends.

While Cruise deserves credit for putting a human face on things, his offscreen team certainly worked wonders as well with the source material, a television show which first ran from 1966 to 1973 before getting revived in 1988 to 1990. With delightfully knotty plotting by Steve Zaillian and David Koepp, who wrote the screenplay with Robert Towne, this is a movie worth paying attention to so you know what the stakes are and who’s doing what and why. The sequels may strip the story down to make more room for action, but there’s still something pleasurable in watching this movie pace itself with the thrills. By taking its time with both the early embassy mission and the later CIA vault heist, the movie shows us two things. One, we get to see how an IMF team works and all the little gadgets they get to use, and two, we see how even the slightest unplanned error or variable can quickly tip a successful mission into a catastrophe. And who better to conduct these nerve-shredding sequences than the Master of Suspense from the film brat generation? Enter Brian De Palma, who wisely chose to accept the mission of bringing this movie to the silver screen.

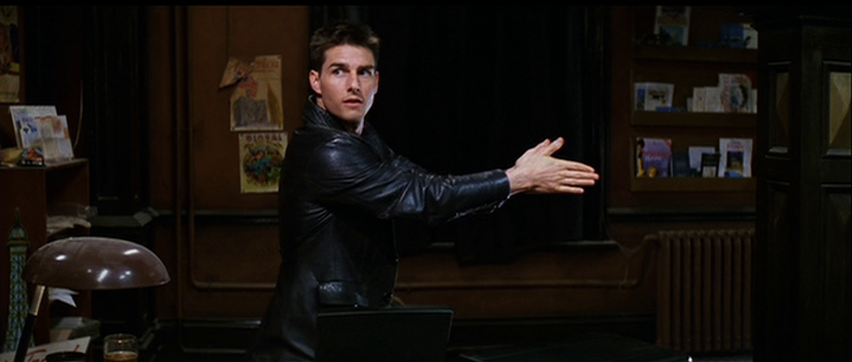

With De Palma directing, we get plenty of Dutch tilts, of course, but the real treat is watching as he blends the eventual tension with a whiff of humor. Forget the questioning cruelty of Jason Bourne or the older escapism of James Bond. As De Palma understands it, we’re here for thrills and chills, to be sure, but we’ll take some laughs too. And he delivers on all fronts. Take, for instance, the moment when Hunt is inches above the pressure-sensitive floor in the CIA vault, after Jean Reno’s Franz Krieger loses control of the rope holding him aloft. We’ve seen how sensitive the floor is earlier, after a single bead of condensation from a glass hit the ground. And yet, while remaining tense, there is something delightfully silly as Cruise flaps his limbs about, as if he could achieve lift velocity to avoid hitting the ground. Much like Cary Grant getting chased down by a barnstorming plane in North by Northwest, De Palma finds the line between sublimity and silliness, managing to ride it for the entire movie. How else to explain the concept of lifelike masks characters tear away with almost gleeful abandon, or the decision to stop the movie’s momentum for a quick sleight-of-hand performance? And when you have spies breaking into the most heavily secured room in the CIA using nothing more than a quick costume change, plus smoke and mirrors, you can’t help but admire the audacity of it all. Forget the heady conversations around who the real mole is, the movie implies. Instead, how about a show?