It’s one of the moldiest old clichés in holiday movies to describe such and such a plot point as “a Christmas miracle” (or, if you’re Homestar Runner, a “Decemberween Mackerel”). A Charlie Brown Christmas avoids it. Maybe that’s because it’d be redundant. The special’s existence is a Christmas miracle in and of itself.

It does everything an animated special should never do. It has a nonprofessional cast, some of them not even old enough to read their scripts. It doesn’t just have an explicitly Christian message — it stops dead so a character can literally preach at you. It tries to build to an emotional climax it couldn’t possibly earn in just twenty minutes, and it barely even tries, using up most of that run time on gags that have nothing to do with the core story. It was thrown together in six months, after Coca Cola picked it up under the condition of having it ready for Christmas. And it looks it, too. Charles Schulz wouldn’t even call the result animation — look closely at the credits, and you’ll see he insisted on calling it “graphic blandishment” instead.

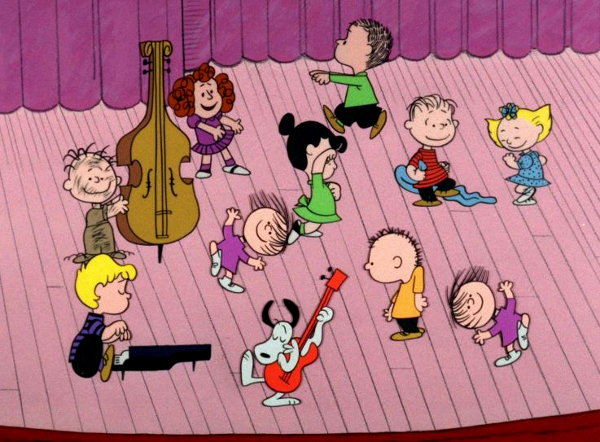

And yet, it’s a masterpiece, one that doesn’t just deserve its place in the canon of Christmas movies but to move up to the grown-ups’ table of cinematic classics. Yes, the animation is, by any objective standard, awful, and the scrutiny of annual viewings has not been kind. There’s only slightly more movement to it than the legendarily shoddy cartoons Hanna-Barbera was making at the time. Some of it wouldn’t even look out of place on Clutch Cargo. The stars are five-pointed shapes right off a sticker sheet that “twinkle” by spinning around. It’s a lot less impressive when Linus knocks the can off the fence when you notice he’s apparently standing inches away from it. The scene of everyone dancing to Vince Guaraldi’s new composition “Linus and Lucy” is iconic, not just because it’s a brilliantly structured running gag, but because of how hilariously terrible the animation is. What are some of those moves?

But director Bill Melendez was a veteran of the classic Looney Tunes, and he knew how to make the most of his limited resources. Just look at the animation on Snoopy when he sneaks out from under Schroeder’s piano. It’s both perfectly human and perfectly canine as he sheepishly looks back and forth before dancing on the piano in beautifully liquid movements, then slowly coasts to a halt as he realizes he’s not wanted and slinks away, almost flat to the ground.

Earlier in that scene, Melendez shows he knows how to turn his animation limitations to his advantages in the special’s funniest moment. Lucy’s unhappy with all of Schroeder’s improbably skilled performances of “Jingle Bells,” until he finally gives up and hammers it out with one finger. It wouldn’t be nearly as funny if we weren’t just watching that one finger bang up and down while the rest of the frame stays still. Even a flat-out mistake can improve the product. Schroeder’s eyebrows suddenly get thicker when Lucy says Beethoven isn’t so great. It’s almost certainly because an ink-and-paint girl grabbed the wrong brush, but it makes Schroeder’s disappointment hilariously palpable.

And the lack of movement creates an indelible mood that more technically proficient animation couldn’t match. All that frenzied, maximalist motion wouldn’t fit the atmospheric stillness of Melendez’ approach, and that may be why A Charlie Brown Christmas has endured while “better” animation is forgotten.

He couldn’t afford very many artists to create Charlie Brown’s world, but he hired the best available to him. The watercolor backgrounds are simple and flat. But they’re full of wintry, melancholy beauty, using heavy negative space to make us feel as small as poor Charlie Brown, or full of blindingly garish color to show off the hollowness of those awful aluminum Christmas trees.

The ridiculous and the sublime sit side-by-side in A Charlie Brown Christmas. The haunting chorus of “Hark the Herald Angels Sing” follows right after the kids cost-effectively decorate the sad little tree by crowding around it and throwing up their hands at random. Even during the chorus, the kids all stop to catch their breath at once, which always gets a big laugh from my family without breaking the deadly seriousness of the moment.

Better than other, more respectable movies, A Charlie Brown Christmas captures the reality of loneliness and depression, especially for a child, even if it is hidden in bright colors and simple shapes, or maybe because of it. And maybe that’s what allows it to capture the other side of the coin just as well, in that final moment of powerful catharsis.

Because at the end of the day, the technique isn’t what matters. Schulz and Melendez captured something here, and how they did it really isn’t the point, if it can be explained at all. There’s certainly no reason Linus’s big speech should work as well as it does.

Whatever the complainers say, “the reason for the season” is such common knowledge that no one, at this late date, needs to be told about it. Many of us have heard the nativity story so often it’s lost all meaning, and on paper Linus doesn’t give it any, just reading the story from the Gospel of Luke without any context. And yet this untrained child playing Linus gets at something more experienced storytellers can’t. Schulz had to fight for this scene, and he was right. What should be insufferably preachy instead becomes a moment of pure spiritual transcendence, both for Charlie Brown and the viewer, or at least this one. And that’s where Melendez’ minimalism really comes in, cutting out the chatter so Charlie Brown, and all of us, can reflect on Linus’s words in the silence.

A Charlie Brown Christmas is a document of a time when Christmas’s slow transformation from a small religious holiday to an inescapable marketing juggernaut still seemed escapable. The “War on Christmas” rhetoric is louder than ever, of course, but none of its fiercest propagators seem to realize they’ve switched sides. Schulz recognizes that spirituality is incompatible with the world of commerce. This is a story about substance winning out over flash. But that isn’t how it went in reality. The searchlights at the Christmas tree farm are barely a joke now. It’s wild, isn’t it, that so many corporations saw messages of selfless giving and thought, “We can make money off of that!” It’s fitting that another Peanuts special, It’s the Easter Beagle Charlie Brown charted the holiday’s continuing commodification with a sign advertising “Only 246 Days Until Xmas.”

And along the way, the punditry mistook the flash for the substance. Schulz’s generation would have been horrified by Starbucks selling Christmas-themed coffee cups, but now the Fox Newsers are yelling at Starbucks for taking them away. Every year, we’re subjected to the rantings of Snoopys who think they’re Linuses. Instead of being offended to be so shamelessly pandered to, today’s Christians crusaders demand to be pandered to. Look no further than the obscenity that is Kirk Cameron’s Surviving Christmas, an hour-long rant where someone making all the same points as Charlie Brown, that Christmas has been swallowed up in flash and consumption, is made out to be the bad guy, that was somehow still sold as a “faith-based film.”

Maybe that’s why A Charlie Brown Christmas is so enduring. In a way, it argues against its own existence — Coca Cola’s sponsorship meant including plugs for the product in the middle of the special, including, horrifyingly, at the end of “Hark, the Herald Angels Sing!”

Mercifully, that footage has been excised, if only because the show’s succeeding sponsors don’t want to advertise their competition. Whatever has been added to it, the core of A Charlie Brown Christmas is still true and beautiful. Instead of dating, it only becomes more relevant with every Christmas season that goes by, and it’ll probably continue into the indefinite future.