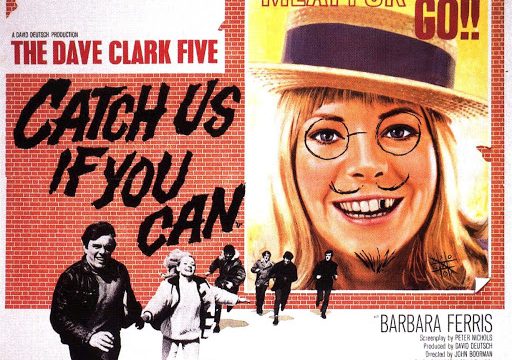

Studios were so desperate to cash in on the success of the Beatles’ 1964 movie A Hard Day’s Night that John Boorman lucked into the kind of deal most directors only dream about. No, not working with the Dave Clark Five — working with a producer willing to give a first-time director carte blanche. That producer, Nat Cohen, sold the US rights to Catch Us If You Can (which was renamed Having a Wild Weekend in the States) to Warner Brothers for more than its projected cost, so the movie was already turning a profit before the cameras even rolled. As long as Boorman stayed under budget, Cohen didn’t care what he did.

So what did Boorman do with this freedom? He and screenwriter Peter Nichols crafted a movie in which a young man and woman hit the road only to discover that there is no escape (a standard theme in road movies) and their spontaneous act of rebellion is quickly co-opted and controlled by the same people they were trying to escape from. Released between the Beatles’ first two movies, Catch Us If You Can responds to A Hard Day’s Night’s cheeky enthusiasm with a jaded world-weariness. Yet it seems more adult — its cynicism is more mature than the absurdist Help!

Catch starts wacky enough to reassure anyone wanting another movie with a British Invasion band. While the catchy title song plays, we see the group members wake up one by one inside a large, prop-filled Gothic house they share, a precursor to the Beatles’ joined townhouses in Help! or the home shared by the Monkees in their TV series. The Dave Clark Five are not playing themselves or even musicians. They’re playing stunt men, by Clark’s request. So while you hear their music on the soundtrack — the songs are good and typical of the era — you never see them performing, which seems to eliminate the main reason their fans would want to see them in a movie.

During a break from filming a meat advertisement, Steve (Dave Clark) and Dinah (Barbara Ferris) decide to leave and drive off in a stolen Jaguar. They have vague plans of heading to an island she wants to buy off the west coast of England. Shots of them driving around London past ubiquitous, large ads, all featuring Dinah, recall some of Godard’s mixing of advertising with cityscapes. These ads might have seemed like a blight then, but they’re nothing compared with how much advertising one sees in cities now. Leon, an executive at the ad agency that hired Steve and Dinah, has junior members at the firm try to track them down even as he exploits the “young lovers on the run” story for as much free publicity as possible. When the police are close to nabbing them at a party, they’re advised, “[We] don’t want them caught till the press arrive.”

Like all road movies, it’s a series of vignettes, disappointments that keep pushing the characters onward until the Final Disappointment. Outside of London, Steve and Dinah meet a group of lethargic, hipper-than-thou squatters in an abandoned building that, unknown to any of them, is also used by the military for training exercises. It’s jarring to hear one of the squatters bluntly ask if they have any pot or heroin, then insult them as “normal” when they don’t. Later, while hitchhiking, they’re recognized by Guy and Nan, a middle-aged, middle-class married couple who take them to their townhouse in Bath to hide out until Steve’s friends can join them. Guy pairs off with Dinah to show her his collection of antique film memorabilia while Nan’s scenes play like a British version of The Graduate. But they’re clumsy seducers, symbols of what not to become. As soon as Steve and Dinah leave the room, they can hear the heretofore pleasant Guy and Nan bickering sharply with each other. It’s presented as one more sign of the adult world’s hypocrisy, but just as middle-aged me thinks Mrs. Robinson is fabulous and feels sorry that she has to amuse herself with the schlubby Benjamin, I like Guy and Nan. They’re much more interesting than Steve or Dinah, and I miss them once the movie moves on. It’s telling that when everyone goes to a costume party, Guy and Nan spend their time with each other, even kissing, rather than mingle with the crowd.

It’s a dour movie. It’s not helped by a leading man who seems profoundly uncomfortable in front of the camera. He’s referred to as “saturnine” several times by other characters; this is probably a bit of self-aware humor. Dave Clark was not a natural actor or believable as a stuntman. Realizing this, Boorman cut many of his lines, but this silence only makes him seem moodier. But beyond Clark’s non-performance, the movie itself is consistently downbeat. Shot in black and white, it doesn’t have the rich contrast of film noir: it’s grey like newsprint. Boorman’s background was in documentaries for the BBC, as opposed to Richard Lester, the director of A Hard Day’s Night and Help!, who had previously made silly shorts and musicals influenced by Warner Brothers cartoons. Boorman wrote that Peter Nichols was “by nature deeply pessimistic” and that he only took on the project because he needed the money. No one sees corruption as clearly as someone who has to do something they don’t want to for money.

This mistrust of being exploited, a fear that your natural, spontaneous actions could be instantly co-opted to sell something, was prevalent in the punk era and had a resurgence in the “alternative culture” of the 1990s. But now? In this era of Instagram influencers and YouTube stars whose primary talent is being cute, I suspect many of them would be jealous of the attention lavished on Steve and Dinah for skipping out on their jobs and driving to the coast. The two eventually discover that the island Dinah wanted to escape to isn’t even an island when the tide is out. Leon the ad exec points out that he just walked to the “island” and waited for them. With its perfectly ironic title, Catch Us If You Can foresaw the day when marketing would trump everything, particularly what we mistake for personal actions or thoughts. It’s a strange sentiment on which to base a movie aimed at teenagers.