Boyhood‘s final vignette finds Mason (Ellar Coltrane) wrapping his mind around the roommate selection process for college residents. In a conversation with his mother, Olivia (Patricia Arquette), he vacantly wonders, “Maybe there are only six types of people in the world, and we aren’t willing to realize that we are less interesting than we believe.” At this moment, his mother is shown visibly upset, complaining that his absence will leave her with nothing to hold on as part of her life. The poignancy of the film is summed up in an antithesis of Arquette’s words; life is a series of milestones to Olivia, but the audience knows, reinforced by Linklater’s film, that we judge and remember our lives through arbitrary occurrences and stray memories.

There’s certainly a truth here; Boyhood‘s strength lies within how it narrates life – or, to be more precise, how it narrates temporally linear happenings relating to a single person. Cinema usually assumes that the audience wants a money-shot structure in relation to the characters it portrays. The climax is the wedding, or the graduation, or the birth of a child – an assumption that makes intrinsic sense. But, personally speaking, I know it isn’t true – I barely remember my high school graduation, for instance, three years after the fact. Instead, Boyhood realizes that the family gathering after graduation is just as worth showing, forgoing the graduation for the sake of the moments after; similarly, we watch him camp with his father (Ethan Hawke) for maybe-not-the-first-time, and we see him smoke weed for probably-not-the-first-time. In this way, Linklater takes commonly shared experiences and strips them of the weight most movies would grant. One could call the movie realistic in approach, but what really matters is that it is, in theory, a refreshing and unique disposition towards fiction filmmaking and storytelling.

But when someone quotes Arquette’s speech to highlight the movie’s successes, they have to ignore the scene’s other revealing line, stated in almost diametric opposition to the movie’s assumed purpose. Mason wonders for a second if he’s really as special as he, being the eighteen-year-old he is, has believed up to this point; but rather than choosing to start distinguishing himself with meaningful introspection, he seemingly gives it no more thought. He continues to be partly defined, whether Linklater intended it or not, by his unremarkability.

Remarkability is subjective. To say so, in a way, is to say that variety is the spice of life. The point I’m trying to make, though, is not that I didn’t find Mason interesting (an opinion stated elsewhere). The problem is that if Linklater wholeheartedly likes Mason, the film runs into an unavoidable political problem; and while Linklater could possibly appear to understand that his main character is a boring person – a concept that great movies can certainly utilize – his approach to finding a catharsis in this dispiriting idea only serves to make me more dispirited.

Much of Linklater’s filmography is built around elevating the mundane in various ways, often achieving interesting results. To use the word “mundane”, though, might be revealing; for me, his trademark philosophical dialogues are blandly interesting, like personal perspectives told as trivia. Rather, my appreciation for Linklater is for the way his ramblings reveal characters and their relationships. The success of the Before series is in how it differentiates its entries while remaining essentially the same film on the surface; the plot is that Jesse and Celine talk, but the way they respond to each other indicates their opinions of one another, evolving from vacuous admiration in Sunrise to Godard-esque contempt in Midnight. The long-form evolution of a relationship is what makes those films intriguing. It’s fitting, then, that my least favourite of the trilogy is Sunrise, the entry with the least amount of conflict and history. Conversely, Waking Life, in its incredulity toward narrative or character development in favour of sheer philosophy, fails to compel me in any lasting way.

Dazed and Confused works by challenging itself with an intentional lack – a lack of danger – and turning that lack into a strength, allowing the camera to show a group of characters at their happiest moments. Randall, an incoming high school senior, and Mitch, an incoming freshman, are facing their own crossroads on the last day of school: Randall has to choose whether or not to abandon his football team for a group of burnouts he better relates to, thus removing himself from the high school elite; and Mitch has to decide between sticking with his junior high friends and rubbing elbows with the partying high school students, securing him a spot in the future high school elite. By the end, both characters have made the choice to change their social standing. Rather than dwelling on the consequences of angry friends and disapproving parents, though, Linklater illustrates the euphoric rush of a new, promising future. Mitch, home the next morning and still drunk and stoned, lays in bed with “Slow Ride” on his headphones and a giant grin on his face, while Randall and his new buddies drive off into the sunrise. Dazed and Confused minimizes conflict to create a feel-good experience, but it also works to capture the texture of carefree youth. It’s Linklater’s way of nostalgically worshiping the coming of age, an already idealized period of life.

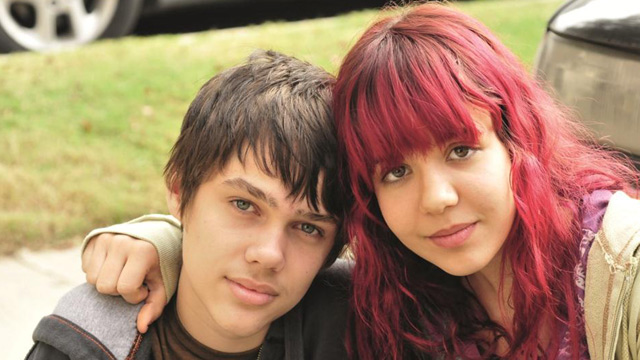

The common response to Boyhood – especially from people in my generation, the millenials – seems to echo my response to Dazed. People react to seeing Ellar Coltrane growing up before their eyes with a feeling of warmth and intimacy. After all, Boyhood is not ethnography; it recreates life as we are meant to know it, instead of showing us something alien. However, what separates Boyhood and Dazed is style and approach. The latter film is purely “about” nostalgia and memory – it represents the act of feeling a fond time, removed with temporal distance. (At this point, I’ll admit that I get a kick out of this kinds of metaphysical idea Linklater likes to present, even when they aren’t incredibly unique.) Its ultrarealist approach to period detail is countered by an unrealistically, perhaps anarchically, utopic sense of life, engendered by a charming cast and Linklater’s free-form script. (To paraphrase one of the most tonally unrealistic scenes in the film, it welts the ass of authenticity with the paddle of joy.) Boyhood, on the other hand, approaches its subject with an almost documentarian sense of realism. I don’t just mean that it’s heavily influenced by Michael Apted’s 7 Up documentary series, which checks on a varied group of people every seven years, 49 years and counting; I also mean that Linklater maintains some distance from the events in the film. Boyhood doesn’t quite attempt to capture feeling in the way Dazed does. This is partly because of its form, composed primarily with medium shots and a moderately sunny aesthetic, that doesn’t match the creative potential of, for instance, Dazed‘s “Sweet Emotion” slow-motion opening sequence; Boyhood‘s attempts at stylistic evocation teeter between subtle and nonexistent. Additionally, Linklater is tasked with illustrating a zeitgeist, the Aughts, at a time when its identity hasn’t been fully established – that is, he has to immerse the audience in Aughts culture before that culture has become readily apparent. But aside from topical references to then-current events, movies, and video games, Mason’s world feels more like an unobtrusive present than a past. The film is not about Mason and his time – it’s merely about Mason.

Because of the film’s unobfuscated, realistic method, the emotional component of Boyhood then rests within the viewer’s ability to emotionally connect with the text of the film, with the story, the characters, and the dialogue being the most important elements. I wish that Linklater exhibited more stylistic flair, if only because I know he has the talent one needs to create engaging sequences; as it is, operating in this realistic mode comes off as more of a handicap than an asset. This wouldn’t be a problem, though, if the text of the film succeeded. To make my argument more simple, I’m boiling my criticisms down to just my problems with the characterization, since Boyhood is a character-driven film above all else. If something about Mason the individual is resonant to the viewer, the film is a theoretical success. Of course, this statement bases itself around a purely subjective viewpoint – of which mine is “I don’t like Mason”. I should stress that I can’t take away your opinion of him; it is yours to keep. What matters, though, is the ramifications of Linklater’s intentions, and both of the possibilities in regard to his intentions present problems.

First, let’s assume that the audience is meant to relate to Mason. It may seem an obvious assumption, but there is a tendency in the film to make Mason as unwaveringly average as possible; so much so, that he becomes either a calculated machine that produces relatability, or a representation of the concept “boring person”. I suspect, though, that Linklater tooled Mason with relatability in mind. His difference, the part of him that makes him relatable, arises from a sense of entitlement that evolves from starry-eyed as a child to cockiness as a teen – evidenced, for example, by his casual avoidance of homework and his elitist “people are stupid” attitude. He is not different for any discernible reason – he is physically and mentally healthy, cis-gender, white, middle-class, and straight – but his entitlement allows him to think he is special. Thus, the audience can either: 1) self-satisfyingly share in his entitlement, or; 2) be aware of his entitlement, and take satisfaction when Mason is made humble by the conversation with his photography teacher or the final conversation with his father. Otherwise, his difference consists either of simple deviations from stereotypes or small variations on tropes. He is arty, unlike a stereotypical dude; he moves from house to house, unlike a stereotypical middle class kid; he is the child of a single mom. But these characterizations aren’t treated deeply in the slightest. Only when the plot point of the abusive stepdad occurs does Mason seem like he will be thoroughly altered from the norm; but once the stepfather is out of the picture, the years of trauma he brought with him seem to have no bearing on Mason. There isn’t a sense of emotional scarring, whatsoever – not even a slight change in disposition. Mason just keeps on being Mason.

The problem with this surface-level relatability is that it normalizes. It strokes the ego of its target viewer; it holds a mirror to the audience and tells them to keep gazing. But as Ebert liked to say, cinema generates empathy; great films don’t hold a mirror directly towards the viewer, but rather do so at such an angle that we can better see a person that was previously out of our vision. What an opportunity Boyhood had to use its unique approach to tell the story of a young girl, a gay kid, or the child of unemployed parents. The empathy that theoretical film would have generated could have been astronomical! Instead, Linklater decided that a “normal” straight white boy’s story was more important anyone else’s, cycling the dominant audience’s empathy back onto itself and furthering the prevalence of stories about straight white males. Further hastening the burial of non-normative stories is Linklater’s title; what it advertises is not the indefinite “A Boyhood”, but the definite “Boyhood”. This film is boyhood, distilled to its essence.

The film’s normalizing tendency becomes most apparent around the point when Mason reaches grade ten. The vignette opens with his second stepdad passive-aggressively judging him for his new coloured nails. He responds with a wishy-washy “I let a girl paint my nails because I couldn’t say no…” kind of statement. His hairstyle looks more European and he has become more fashion-conscious. His voice has adopted a slightly effeminate nasality. He even later says that he has a vehement distaste for sports. At this point, the amount of room for investment the film had failed to reach became apparent to me, and I thought the film was finally beginning to fulfill its promise by making Mason gay. It’s not just that I’m gay and can relate to gay characters; any challenge in his life, at all, would have made the story much more interesting. He could have sustained an injury that left him permanently in a wheelchair, or his family could have run into severe financial troubles and be forced to live a less comfortable life. But soon after, we see him hitting on a woman at a party, and my interest in the character of Mason violently crashed to its nadir. The fact that Linklater seemed to be actively preventing his character from becoming interesting was wrenchingly dispiriting.

At the same time, though, there is the possibility that Linklater directed the movie with a complete willingness to make Mason thoroughly boring. After all, the quote I opened with seems to majorly indicate this idea, as if it is just as important as Arquette’s subsequent speech. Conceiving Mason as unremarkable is an idea that, with the right execution, could be fruitful – something which numerous movies have proven before. Off the top of my head: McCabe & Mrs. Miller‘s lead character, played by Warren Beatty, was defined by a mix of arrogance and impotency that stood in direct contrast to the Western frontiersman archetype. In Crimes and Misdemeanors, the character of Rosenthal was portrayed as a stereotypical upper-middle class doctor in order for his act of evil to unsettle the audience even further. Writing an everyman into the protagonist role works when it successfully engenders a point about the real world, or when the movie comments on the state of being boring.

As I interpret it, Linklater’s overall point could be theorized as such: Life is made not of events, but of moments. Those moments, being what make up life, are exciting simply because it’s the stuff life is made of. The aforementioned editing style is a major contributor to this idea. Mason, being the unenthralling boy he is, is interesting despite being boring, by the nature of cinema; if his life is worth showing, then everyone’s life is worth putting on the screen. The amount of worth audiences have found in his tale is more than enough to prove a boring person can be engaging. But however true Linklater’s point may be, it is completely lacking in depth. After all, what is the point? The idea could be a fascinating one, but it presents problems on a tangible level. Linklater has to sustain the audience’s interest for nearly three hours with his dull character for his movie to work. Stretched out for that long, the point wears thin, especially when Mason gets to his teen years and becomes less likable. The last hour sees his grating nature compound with the movie’s lack of structure to slow the movie to an uphill climb. A major plot development would have not only regained my interest, but it would actually make the movie more unexpected and creative; there is little more engaging in cinema than a surprising movie. The structureless free-form experiment would instead be a mostly-structureless film with a defined third act, something which seems unprecedented in comparison. Or, even better: Mason could have been replaced with another character entirely. As it is, though, Linklater’s film is the elucidation of one single concept devoid of derivation.

Thus far, Linklater’s career is a continual promise with no payoff. There is a masterpiece in him – he has gotten close with Dazed and Confused and Before Sunset. The concepts of his that continue to reward with good movies serve to inhibit the creation of an amazing one. The idea behind Boyhood, to film a story over twelve years of a person’s life, should have led to a film of startling power. Linklater’s flaw, though, was to follow through that concept to the hilt, making a movie purely in service of its single idea. The plot description on IMDb illustrates perfectly the lack of creativity involved: “The life of a young man, Mason, from age 5 to age 18.” Mason from five to eighteen is the plot – and the only plot – of the movie. To see Linklater aim so low with such a lofty idea is majorly disappointing.