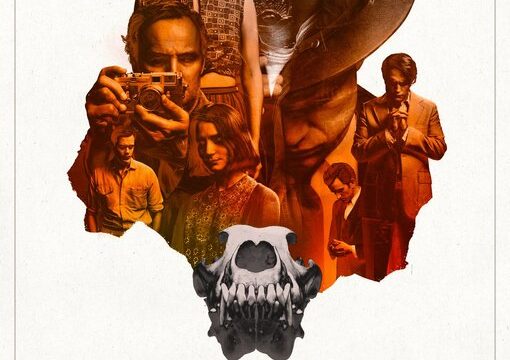

We are all born in the shadows of the past. The characters of The Devil All the Time are no different. This expansive saga, taking place primarily in and around Coal River, West Virginia, begins with U.S. Marine Willard Russell (Bill Skarsgard). He’s returned home to have a child with a local waitress but he’s still haunted by the memories of his time serving in the war. All the carnage he experienced overseas exposed Russell to a level of human depravity he didn’t think was possible. In Russell’s eyes, the only way to fight that evil is with equal levels of terrifying force. Before he passes away, that’s the message Russell instills in his son, Arvin Russell (Tom Holland).

Ah, but it’s not just father and son coping with the past. There’s also corrupt Sheriff Lee Boedecker (Sebastian Stan), who’s worried about his past misdeeds coming back to haunt him come re-election time. Let’s also not forget about serial killer couple Sandy (Riley Keough) and Carl Henderson (Jason Clarke). Carl just lives in the moment photographing people they murder. Sandy, on the other hand, is certainly caught up thinking about how her life has gotten to be filled with blood and torment. Further unifying all of them, plus Reverend Preston Teagardin (Robert Pattinson), is the fact that religion tends to inform their behavior. The Lord is supposed to be merciful. The actions of people who follow him, not so much.

Adapted from a novel of the same name by Donald Ray Pollock, The Devil All the Time is a mighty sweeping narrative. In the hands of screenwriters Antonio Campos and Paulo Campos (the former of whom also directs), there’s a number of admirable qualities in the movie storytelling. For one thing, Devil All the Time has no problem taking its sweet time with the kind of digressions other movies would cut from the script before they even started rolling the cameras. Devil is in no hurry to rush through its wall-to-wall misery, as reflected by its 138-minute runtime. This allows the viewer to truly live in its world, soak in all the details of these seemingly random lives, rather than just rush through it all.

The way Devil All the Time totally commits to both bursts of non-linear storytelling and a sprawling cast is similarly remarkable. Campos is not trying to make a conventional film with The Devil All the Time and that’s especially reflected in its pervasively grim tone. Call each character in this movie a 1994 Nine Inch Nails song, because they’re riddled with hurt. Unfortunately, the execution of the tone is one of the many ways The Devil All the Time is more interesting in theory than it is in practice. For one thing, the way grimness manifests across the individual characters tends to get very repetitive very quickly. There’s a surprising lack of specificity to the on-screen torment that doesn’t make it as impactful as it could be.

In the first 40 minutes of Devil All the Time, we become privy to an avalanche of misery befalling the Russell family. There’s so much traumatic stuff happening here, from discovering a crucified soldier to the death of a family pet. This family makes the twins in I Know This Much is True look like happy-go-lucky Pollyanna’s. All of it should be as traumatic for the viewer as it is for the characters on-screen. But all of these events happen in such rapid succession that they didn’t really leave an impact. You get numb to it after a while, especially when every other character in the movie is informed by a similar sense of woe. Everybody in this movie is Sergeant Calhoun from Wreck-It Ralph, programmed with “the most tragic backstory ever”.

The generic rendering of that anguish is particularly reflected in the female characters. The Devil All the Time is filtered through a male lens, save for a handful of moments with Sandy, we only get to see the world through the male characters. This means the women are around solely to suffer pretty predictable fates (murder, sexual assault, suicide, the works) to motivate the other male characters. It’s disappointing to see The Devil All the Time take such an ambitious canvas and a bold tone and then use them on such derivative material. Compounding the frustrating nature of the production is how author Donald Ray Pollock has been recruited to do omnipresent narration that proves extremely intrusive.

Campos can’t just let visuals or the actors speak for themselves. Pollock’s voice must come in to hand-hold the audience through pretty self-explanatory imagery or character motivations. Similarly, the third act disappointingly dovetails into a series of simplistic showdowns. None of the moral complexities of uber-grim movies like Sorcerer, the various works of Lynne Ramsey or Campos’ own Christine is found in the third act of Devil All the Time. The good guys and bad guys are drawn in shockingly broad strokes. To add salt onto the wounds, it proves shockingly uninteresting to finally see these previously standalone storylines intersect. The actors are doing what they can with this material, but the writing for The Devil All the Time lets them down. All of that bleak build-up leads to a shallow fizzle.

It’s not all bad in The Devil All the Time, far from it. The actors are uniformly putting in good work, particularly Tom Holland, who does a great job expressing simultaneous angst and confusion in the second half of the runtime. A scene of just him and Pattinson having an exchange in an empty Church is possibly the best sequence in all of The Devil All the Time. No distracting narration here, just two actors going mano-a-mano with a well-executed sense of growing dread in their interaction. Sometimes, that’s all you need to make some compelling drama. The Devil All the Time could have used more of that kind of drama. The devil is in the details, as they say. For The Devil All the Time, its generic details betray its lofty ambitions.