Close your eyes and picture the traditional American frontiersman. Chances are, we’ve all got a similar vision of what such a person looks and acts like. First Cow begins with a group of these individuals. A collection of white men adorned in fur pelts with thick beards, gruff attitudes, and a proclivity for violence. They talk about women as just objects they can use for sex and then dispose of. Anything that strikes them as unconventional, they’ll try to slaughter it. The cookie for this group is a man by the name of Cookie (John Magaro). He doesn’t fit the traditional American frontiersman profile at all.

Soft-spoken & considerate with a kind heart, Cookie isn’t the kind of figure we’ve all been taught to imagine was out there in the earliest days of America. Ditto for Chinese immigrant King Liu (Orion Lee), who strikes up a friendship with Cookie. King and Cookie eventually strike up a way to make money. They’ll take some milk from a local cow (played by Evie the cow) owned by the powerful Chief Factor (Toby Jones). They’ll use that milk to make one-of-a-kind biscuits. Nobody else out here has a cow and that means nobody else can make biscuits laced with milk. Cookie and King will quietly take from the upper-class to make food for lower-class citizens.

Kelly Reichardt’s First Cow is all about the sorts of individuals who don’t fit into society’s traditional view of masculinity. A key way Cookie and King don’t fit into that conventional view is simply by being nice to one another. Screenwriters Reichardt and Johnathan Raymond dedicate much of the screentime to emphasizing how Cookie and King connect with one another by just listening to the other person. Their respect for one another is even reflected in a quiet scene depicting the two of them doing chores together. So many of the male characters in First Cow see other human beings as only a hindrance to their own ambitions. For example, Chief Factor, at one point, mentions that killing disobedient employees is a great way to stir up morale in the other workers.

Factor only see’s the people who work for him as disposable objects. He’s far from the only man to see other human beings in this way. What an unfulfilling way to navigate life. Cookie and King find a much more rewarding existence just by being there for one another. Cookie’s sense of kindness even extends to the cow he milks on a nightly basis. First Cow’s most poignant moments come from Cookie’s quiet whispers to this bovine. While Factor sees the cow as just a financial means to an end, Cookie takes the time to impart sincere apologies to the cow for the recent loss of her husband and calf. He may be taking her milk, but Cookie views the cow as a living thing, and not just an object.

The sight of a grown man softly telling a cow “You’re a very good cow” should inspire giggles. Instead, the sight of such genuine kindness in the middle of a dehumanizing world got me all choked up. Much of that comes down to John Magaro’s performance, which is an impressively-rendered creation. Though he tends to speak in a hushed tone, Magaro’s voice always manages to capture your attention. It’s full of such believable empathy. With Magaro’s vocal quality and line deliveries, you never doubt that Cookie truly looks at other people as human beings. Much like that pumpkin path Linus waited for the Great Pumpkin in, there’s nothing but sincerity as far as the eye can see in Magaro’s First Cow performance.

Magaro and the rest of the First Cow cast are framed in a 4:3 aspect ratio. Much like with Robert Eggers and the 1.19:1 aspect ratio he used on The Lighthouse, a more limited amount of space in the frame has fired up the visual imagination of First Cow director Kelly Reichardt. Impressive pieces of blocking and staging abound throughout the film that makes heavy use of deep focus. There are so many layers of detail in any given image throughout First Cow, the viewer is never just focusing on the foreground or on the background. Maybe the most memorable image is a nighttime shot depicting King looking guard on a tree branch while Cookie heads off to the cow. No, wait, it’d actually have to be the Lord of the Rings-esque shot where Cookie is hiding from the hunters. Or maybe it’s…well, clearly, there’s a lot of incredible images to pick from in First Cow.

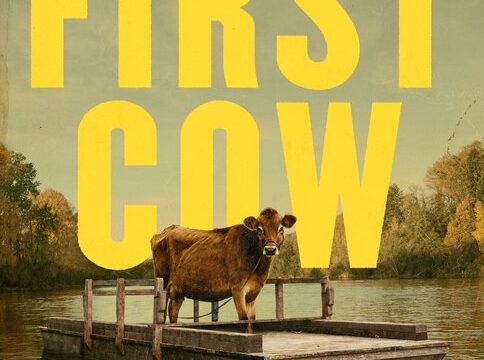

First Cow also makes use of a great Autumn-esque color palette heavy on yellows and oranges that instills a sense of melancholy into the film. Autumn bring the bittersweet realization that another year is coming to an end while First Cow’s melancholy nature derives from the fact that its central friendship cannot endure in a world that puts money over people. This despondent aesthetic is reinforced by the restrained score by William Tyler. His compositions frequently make use of just a string-instrument getting lightly plucked. It’s the kind of music you might have heard around a campfire in the frontier days. It’s an unorthodox score, but then again, First Cow is all about eschewing convention.

Cookie and King are not typical frontiersmen. The qualities that make them different are what make them outcasts in the late 1800s. It’s easy to imagine their sensitive qualities also making them an anomaly in the world of 2020. No matter what age you live in, money is always given far greater importance than the lives of people. But as the final scene of First Cow emphasizes, money is immaterial compared to being there for somebody you care about. Kelly Reichardt’s execution of that theme makes First Cow’s such a divine bovine shrine to the importance of kindness.