The emotions that drove Hideo Kojima’s creative impulses in making the Metal Gear Solid sequels uncannily line up with the famous Five Stages Of Grief (especially if you don’t buy into the myth that everyone goes through all the stages and in a specific order). With the first game simply being a self-contained story – the action before consequence – the second was motivated by Anger. How dare you miss the point of my big artistic statement, Bad Fan? I will construct an entire game designed to humiliate and enrage you! It was wildly successful; fans en masse turned on the game, infuriated by Snake being taken away from them and either uncomprehending or contemptuous of what it had to say. Unfortunately, the one effect Kojima was hoping for was the one that didn’t happen – fans demanded another Metal Gear Solid game that would return the series to glory and tie up the many, many, many plot threads still dangling. Plotwise, the second game ends with Snake, Otacon, and Raiden discovering the existence of the Patriots, a hyperintelligent AI network that controlled information across networks, and it was controlled by a group of individuals called the Wiseman’s Committee as part of a conspiracy going back to America’s founding. Snake and Otacon locate the names of the Wiseman’s Committee and are all gung-ho about setting off to stop them; a post-credits scene has a bewildered Otacon inform Snake that every single member of the Committee died over a hundred years ago (“… What the hell?”). Now, in context, it pretty clearly comes off as part of the practical joke’s punchline – none of this was ever going to make sense or be resolved, because it was a ludicrous power fantasy that required a willing agent to take at face value despite the massive holes and incoherent logic, and this was Kojima giving us all fingerguns and a smirk as he walked out the room. But enough dimwits players took it at face value and assumed it was a genuine hook for a sequel, to the point that, gaming culture being what it is, they sent demands and even death threats to get the sequel made. What’s fascinating is that not only did Kojima deliver, he decided to go into it with a Bargaining mindset.

Whether he had gotten all the anger out of his system, conceded that MGS2 had simply agitated rather than educated players, or simply latched onto another goal with the same fervor he had delivering a thirteen hour middle finger, Kojima decided to make this game as accessible as possible while still living up to the Metal Gear Solid spirit. This is still a game with long lectures on geopolitics, science, morality, and action movies, but where the second game denied a cheap power fantasy at every turn, this one leans into them. Our hero is a gruffly-spoken cigar-smoking lightly-bearded white man who enters fights with an earned confidence, and he’s up against a clear and quite horrible threat to the entire world. And you know, I’ve learned to be okay with that. My relationship with this entry in the series is the one that has been most in flux, because I first thought of it as fun but ultimately empty, saying almost nothing that the first two games hadn’t already and doing it in a way that flattered the player as opposed to challenging them. But I’ve come around on it; aside from the fact that it does do and say unique things that expand upon what the franchise as a whole is about, I’ve come to respect that it’s just as tightly crafted as the second game, and in fact could be seen as having learned the lessons it tried to teach. Everything in this game exists to advance a specific point, and while some of it is fairly unsubtle – like the way the cute doctor on the radio will lose her medical licence if you fail, adding another level of stakes onto the threat of worldwide nuclear war – it all comes together in the ending, emotionally if not plotwise.

More importantly, though, I’ve come to see the value of speaking the same language as everybody else. There’s still a large place in my heart for Metal Gear Solid 2 (“A large place?”), and I still live in hope that a puzzlebox story will trip me up and play with my heart and soul with the same level of expertise, like a sheepdog herding sheep. But I’ve also come to accept the highly personal nature of cleverness. I might make justified digs at people who didn’t engage with Metal Gear Solid 2 at all, let alone to the point that I did, but the fact of the matter is, MGS2 is a cult item with a small but dedicated fanbase fighting against a massive tide of bad will, whilst MGS3 is by far and away the most beloved entry in the franchise next to the first. There are people that won’t hear what someone has to say in any other language than their own, and there are people who will never hear certain messages no matter how you dress them up; for whatever reason, I’m perfectly okay with being told to eat shit to a high level and intensity if the end goal is funny enough, and I love being jerked around by a sufficiently clever prankster or magician and analysing how they pulled it off, and for whatever reason, most other people aren’t. There comes a point where you have to decide if you’re amusing yourself or everyone else.

Anyway, I’m over 900 words into this essay on Metal Gear Solid 3 and haven’t actually talked about the game at all! It wouldn’t be Metal Gear Solid if it wasn’t way too fucking much, and it wouldn’t be Metal Gear Solid 3 if it didn’t have massive amounts of context given. (SPOILERS from this point onward). This is the story of the One Bad Week that set an ordinary soldier onto the path to becoming the supervillain that nearly took over the world and inflicted two separate Oedipus complexes (complexii?) on his cloned sons. The year is 1963. A man we only know as Jack joins FOX, an experimental new commando unit designed for stealth missions in which a single man is dropped into enemy territory, and is assigned the codename Naked Snake. His first mission is to retrieve a Soviet rocket scientist named Sokolov, a defector to the US who was returned as part of negotiations of the Cuban Missile Crisis (more on that later); Snake’s mission is the US playing some highly illegal takesie-backsies, and it requires him to extract Sokolov without leaving any trace that the US was involved. His only support is over the radio – his commanding officer, a medic with a guide on surviving in the jungle, and to his great surprise, his mentor, a woman known only as The Boss. She’s a legendary soldier who, amongst other things, created both the (real) Special Forces and (fictional) Cobra Unit, and stormed the beach at Normandy. She served as Snake’s mentor for ten years, developing a form of close-quarters combat with him, before suddenly vanishing, breaking Snake’s heart; his first conversation with her turns him from badass soldier to hurt child wondering why Mum had to go away.

When Snake gets to Sokolov, he discovers the scientist has been press-ganged into building a nuclear equipped battle tank that can launch missiles to anywhere in the world – a tank that he calls the Shagohod (which he translates as ‘The Treading Behemoth’, though a more technically accurate translation would be ‘Step Walker’). As Snake is escorting Sokolov to the extraction point, The Boss suddenly appears alongside a GRU Colonel named Volgin, beats nine colours of shit out of Snake – the moment where she breaks his arm always gets to me – throws him off a bridge, and takes Sokolov, the Cobra Unit, and a few Davey Crockett nuclear missiles with her as she defects to the Soviet Union, one of which is used on the facility Sokolov was working on as Volgin and The Boss helicopter out. Needless to say, the effect is disastrous; Volgin and the hawkish GRU are a competitor to Kruschev’s KGB at the time so he’s only just preventing them from starting war, the plane holding Snake’s support team was spotted in violation of Soviet airspace, and Snake and his team are all one step away from a firing squad if they’re proven to be part of The Boss’s defection. This all coalesces into a single mission that can fix everything: Snake must infiltrate Volgin’s facility, destroy the Shagohod, and kill both Volgin and The Boss. This also coalesces into a single, simple emotional hook: Snake must choose between his duty to his country and his love for his mentor.

When this Snake is introduced to us, he’s far more naive and thoughtless than Solid Snake ever was. Before The Boss defects, she tries to imprint not just a soldier’s morality but a Soldier Morality onto him, in which he has to prioritise the Mission over his personal morality, his loyalty to others, and most meaningfully his loyalty to the US government, and he never quite manages to get what she’s trying to say (“I follow the orders I’m given. I don’t think about politics.” / “That’s not the same thing.”). The Boss is a woman who believes in things, and knows that this means knowing about the things you don’t believe in; Snake hasn’t thought about what he believes in at all, and her defection has forced him to muddle through a complicated situation the best he can. Plotwise, this is some generic James Bond-meets-Rambo-meets-The–Great–Escape nonsense, but it’s all in service of Snake trying to work up the nerve to kill the person he loves more than anyone or anything else. The ultimate twist of the game, however, is that she never actually defected – her original mission was to act as a double agent, a plan that went to hell when Volgin fired the nuclear missile, forcing her to lay down her life, the lives of the men in her Cobra Unit, and her reputation as America’s greatest hero to preserve world peace.

What makes it interesting is how the game shows ‘world peace’ as a morally murky position. Snake discovers that Volgin is funding the Shagohod project through something called the Philosopher’s Legacy – after World War I, a group of twelve prominent people from the US, China, and the Soviet Union formed the Wiseman’s Committee to steer the world away from warfare; they developed a well-funded conspiracy called The Philosophers, and when the last member of the Committee died in the Thirties, the Philosophers’ goals became corrupted and factions developed that fought over the massive funds of the organisation. Volgin’s father was a prominent member of the Philosophers, and his part of the Legacy was passed down to his son. What I love about this is how it shows a System on both a micro and macro level; much like Order Of The Stick, this game shows degrees of Good and Evil, but it also shows how a System can support Good or Evil choices. Volgin is a vile mass-murdering rapist, but he’s also only able to commit evil on the scale he does because he happened to be in the right place at the right time. It doesn’t deny his responsibility for his choices but it does show where his choices came from. This is a conspiracy-heavy worldview that makes more sense to me than most conspiracies I’ve been presented with – not of small groups of people making single ludicrous actions with lots of money (like, say, faking a terrorist attack on the World Trade Center), but of interlocking power structures and patterns of behaviour that generate money and power for some at the expense of the lives and dignity of others.

The conclusion Snake comes to is that not only did The Powers That Be sacrifice the greatest hero that ever lived to settle a dispute over money, they used him as the tool to do it. An obsessive Metal Gear fan knows that he’ll go on to create a nation of soldiers who will work for the highest bidder and threatening to destroy the world if they don’t comply; seeing this makes a fan understand why he did it – a world that allowed The Boss to die is not a world that is worth protecting. He’s already a bad person who effectively believes he’s going to hell anyway; what’s a little nuclear holocaust on top of killing The Boss? It’s clarification that makes him sympathetic and understandable that, like Volgin, does not completely deny his choices – we are also seeing Solid Snake’s backstory, in that he too was disillusioned by murdering his parental figure and by being used by his government to commit awful acts for petty reasons, but chose a path that prevented nuclear holocaust. This game is the finest example of a prequel ever made, completely dodging all the pitfalls that everything else, especially the Star Wars prequels, ever fell into.

All the best prequels are set long before the events of the ‘main canon’. The Star Wars prequels are famous for both their ridiculous explanations for things that happened in the original trilogy (most infamously, midichlorians ‘explaining’ the Force) and their ridiculous attempts to shoehorn in beloved characters (most infamously, Chewbacca knowing Yoda). Meanwhile, my muted reaction to the Order Of The Stick prequel books was rooted in the fact that they didn’t feel like they complicated the narrative enough to justify their existence; I already knew Redcloak was deep in the Sunk Cost Fallacy and justifying his actions as being revenge for his people, and telling me his [REDACTED] got [EXPLETIVE DELETED] doesn’t change how I perceive him or how I expect him to act moving forward. MGS3 is set so far back in time that the majority of the original cast hadn’t even been born yet, and the only original characters are Naked Snake/Big Boss and Revolver Ocelot (here, simply known as Ocelot). So we have one person who we only knew of through reputation, one person who has fifty years to become the dude we know and love, and a whole cast of characters whose paths are a complete mystery to us. The only thing we know for certain is that the world will still be standing, and of course the fact that this is a video game and the player is perfectly capable of failing to achieve Snake’s goals injects the tension that would otherwise be lost.

What’s great is how all these ideas are sold through a mixture of clever, showy plotting and conventional genre crap. Everything is designed to get us to that ending, and that doesn’t just mean plot turns but experiences that we have to go through for it to make emotional sense. In terms of plot, there’s the way it so wildly and yet clearly stacks the deck – there’s nuclear holocaust and the threat of a firing squad forcing Snake to engage with the story, injecting thrills and necessity into every decision he makes – but Kojima also injects triumphs and joy to keep us constantly engaged and wanting to continue on with the story. There are lots of little things the game does on this level, mainly involving Snake’s quirky support team; Paramedic is a giant movie buff who tells Snake about everything from Plan 9 From Outer Space to Guns Of The Navarone, Snake frequently disgusts Paramedic with the sheer variety of things he’s willing to eat, and Major Zero is extremely British. My favourite device, though, and the most obvious, is Volgin. He exists purely as a figure to hate, a supervillain who murders, rapes, and tortures people with no regard for human life. As you advance, you frustrate and inconvenience him, and the final fight with him is both spectacular and provides catharsis before you fight The Boss. Ultimately, the feeling of guilt and betrayal at the end overshadows the entire experience in your memory, but a whole spectrum of human emotion is what gets us there.

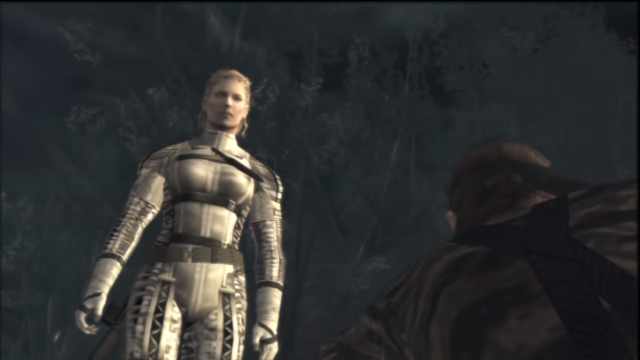

There’s also the bombastic, unsubtle style that makes the games joyful to play if you’re willing to get into that mindset. This is one of my favourite cutscenes in the game, because it distills so much of the Metal Gear ethos into one scene – the action is utterly preposterous and Ocelot overexplains what he’s doing, but it works because of the total commitment to it – both in terms of how the animation was done through mo-cap, which means a guy actually had to juggle three revolvers, and in terms of emotional commitment. Ocelot is a cocky little tryhard who definitely would learn to juggle revolvers simply so he could intimidate people for no good reason, and The Boss is a brilliant soldier who outclasses everyone around her and could definitely keep track of which revolver had the bullet in it. On top of this, the camera gleefully swoops and glides and slomos around and the sound design is a mixture of near-constant music and comic book sound effects, elevating all of this into some larger-than-life myth (though never losing where all these people are in relation to each other). It has the clear emotional logic of a dream, and the entire game is filled with sequences and moments like this. The ending, as it needs to be, is even stronger; every Metal Gear game ends with someone laying out a big speech over a montage, and this is the best of all of them.

The narration is actually a tape left behind for Snake by Eva, the game’s Bond Girl, and she begins by explaining who she really is and what her true motivation was. There are three cliches that occur during this sequence: a sad piano version of the wacky Bond theme that opens the game, flashbacks to scenes earlier in the narrative, and the music shifting to a reprise of the main theme of the series. I’ve never seen anything deploy these cliches as artfully as this sequence does – the flashbacks and sad piano song kick in on the precise, exact point that Eva shifts to talking about The Boss, with the latter elevating her into something uncanny and larger than life and the former turning her into a puzzle demanding to be solved. When the sequence shifts from Snake listening to the recording to him sadly accepting his reward (look, we all agree “I hereby award you the title… of BIG Boss!” is mood-destroyingly funny), the music shifts to the orchestral take on the series main theme, something that’s been carefully avoided almost all game – there’s a surf rock parody of it that plays in the room of an informant, and the main theme of the game is carefully written to recall it without sounding like it at all, but otherwise it only came in when Snake killed The Boss, and now the sequence is nearly wall-to-wall with it. As if to say, yes, this is where it all truly began. I say nearly, because it is paced out so there are moments where it’s pulled back, and the flashbacks are pulled back too until Eva digs into the changes in the plan that forced The Boss to sacrifice her life. The music starts building and building as she gets closer and closer to the crucial moment, and when Eva finally spills the depths of The Boss’s idealism, the music explodes and billows out, the melancholy and heroism and triumph of the music living up to the melancholy and heroism and etc of The Boss, and it always reduces me to tears.

That really describes the game as a whole – a series of unsubtle devices strung together to create a specific emotional arc, one with peaks and valleys that coalesces into a profound experience. I was going to make a self-deprecating joke about how playing it for the first time at the age of sixteen may have made me more amenable to flawed or awkward aspects of the presentation, but then I considered – do I really want to downplay having an earnest reaction to an earnest work of fiction? This is a thoroughly commercial work of entertainment designed from the ground up to shut them fuckers up entertain people alienated by the deliberately alienating MGS2, but it’s not in any way compromised – this was a labour of love, and Kojima believed in everything from the lectures on holding onto your morality in changing times to the loving references to The Great Escape. He wrote the jokes because he thought they were funny; he was distraught by the sad plot turns; he cared about the characters not just as vehicles for his views or as plot devices but as individuals with their own emotions, interests, and dreams. I’ve always been struck by a moment that comes late in the game; Snake is caught by the bad guys, tortured, and blinded in one eye by an errant gunshot. In a thrilling sequence, he escapes through the sewers (including a massive reference to the iconic moment in The Fugitive) and into the jungle before finding Eva behind a waterfall. After she gives him an eyepatch, there’s a moment where a moth flies past Snake, and as the female vocals from the theme song gently waft through the soundtrack, he tries grabbing it out of the air and misses. It’s not something that advances the plot (in fact, it doesn’t slow him down at all), and it’s not really connected to the themes except in esoteric ways. It’s just the story stopping for a second to acknowledge that Snake losing an eye is terrible.

(Though it does come back later in a moment equally as small and equally as soulful)

This is broadly connected to what I love about the game, the series, and the game’s context within the series. Beloved Soluter Son Of Griff has remarked that auteur theory is ironically most applicable when applied to genre works and B pictures, when a director’s habits and views keep shaping anonymous material. Hideo Kojima could never really write an anonymous work and Metal Gear Solid 3 is clearly the product of his imagination, but it’s also clearly made with an eye towards being pleasurable. Consider something like The Wire, where David Simon is gonna make you eat your vegetables and you’re gonna goddamned like it. Consider something like Captain America: The Winter Soldier, where a bowl full of sugary crap is sold to you as one part of a nutritious breakfast because look – it has bits of social commentary in it! Half-baked and ill-thought-out, but it’s there! MGS3 is interesting as a model for fiction that exists as a vehicle for a particular author’s particular views but presented in as accessible a format as possible; the game could not be thought of as a dramatically structured work, but it is a tightly structured one in which Kojima’s pacifist, humanist, insatiably curious vision is the fuel that powers the machine.

Good storytelling is about people making choices and those choices being important. The joy of Metal Gear Solid is seeing choices that are of apocalyptic importance; one of the criticisms of the MCU and other blockbusters of the past decade is that they frame all their stories around the saving of the world in a way that flattens the tension, but MGS avoids this by taking the death of even a single person as a terrible thing. One of the basic gameplay elements is that you don’t actually have to kill anyone – you can knock people out, either with a chokehold or with your tranquilizer gun. Late in the game, there’s a boss fight that actually takes place in the afterlife, with The Sorrow – the Cobra Unit’s psychic medium, long dead by the events of the game – showing Snake all the people he’s killed, which involves the player walking down a long path as all the people you’ve killed walk past, able to vampirically suck the life from you if you’re either not careful or have killed too many. Aside from the fact that a pacifist run is inconvenient and hiding a dead body is easier than hiding a sleeping one, I had enthusiastically embraced a new gameplay feature that allowed you to slit the throats of guards you’d grabbed, and so I was profoundly disturbed by the image of people I’d killed walking by me, trying to hold their heads on straight, which was obviously part of the intended effect.

This is a specific manifestation of a general humanisation the game engages in. All the enemy mooks are actually full of personality; on a basic level, they fit ZODIAC MOTHERFUCKER’s rule that characters are more sympathetic when they’re good at their jobs, because they show discipline and intelligence in patrolling and investigating areas, using accurate hand signals to direct each other around, making regular reports and calling in things they hear or see (this all probably sounds obvious when you’re not steeped in a medium where taking cover was a grand advancement in tactics). On top of that, the mooks are full of personality themselves – they can be bored, curious, loyal, vindictive, afraid, and even hungry if you decide to mess with their food. Obviously, this is all part of making it a more enjoyable video game; one of the wallflower quotes I steal the most is that great ownage requires great enemies, and it’s more fun to go up against the cunning and tough mooks of MGS3 than it is most video games. But it goes hand-in-hand with the elaborate backstories and personalities of everyone you meet – people have strange yet comprehensible inner lives that translate to endearing behaviour, and death means wiping those inner lives and that behaviour out of existence. Metal Gear Solid makes the end of the world important by knowing why it’s important; Metal Gear Solid 3 uses that knowledge for an entertaining thirteen-hour story.