The first episode of Home Movies I ever saw was its last. I was sitting at a computer in the “newsroom” where I was interning, senior year of college, maybe a month before graduation in 2004, typing away at some final project that would cease to matter the minute I turned it in. I was in Washington DC, 400 miles away from my friends, lonely and depressed and barely paying attention to the TV in the corner I had for some reason tuned to the Cartoon Network. Home Movies was a show I had actively avoided all semester because of some obnoxious promos, and yet I didn’t bother to turn it off now. And for some reason, I looked up at the final scene, a few people driving away as the view faded to the static of a dying camera. Maybe I was conscious of an ending.

***

It’s remarkable that Home Movies even made it to 2004. The show initially aired on UPN in 1999, the absolute heyday of networks throwing cash at animated series, and executives must have been aghast at what they paid for. Loren Bouchard and Brendon Small’s show built off the earlier Dr. Katz, Professional Therapist — a largely improvised sitcom animated in purposefully rough Squigglevision, where any lapses in character alignment were part of the show. Even by that rubric, the five episodes of Home Movies shown on UPN are so hideously crude and minimalist, they make Tracey Ullman-era Simpsons look like Comedy Central-era Futurama.

And it’s not like the characters were conquering heroes. The show revolved around Brendon, Melissa, and Jason, three eight-year-olds obsessed with making movies, and how they bounce off Brendon’s enthusiastic jock-ish mom and his extremely unenthusiastic, non-jock-ish, and generally hungover soccer coach. Like those Ullman-era Simpsons, the bones of something great are there, but the crudeness makes that hard to see. And in any case, there wasn’t much time to see it. The show was canceled after five episodes.

But somehow, Home Movies got a second life. Adult Swim — the late-night Cartoon Network programming block that was built around stoner re-imaginings of Hanna-Barbera cartoons — put it back on the air in fall 2001, making it their first original show. There were a few changes. Janine DiTullio replaced Paula Poundstone as Brendon’s mom, who had been re-invented as a community college writing teacher with no athletic abilities to speak of. And while the show was still in Squigglevision, it no longer looked like it had fallen into a gutter on the way to broadcast, and post-revival seasons were animated in the slightly less personal but significantly more watchable Flash.

And more importantly, the show realized what it was.

***

The day George W. Bush was elected for a second term, I got my first real job. After a summer and fall of living with my parents in Western New York, half-assedly working temp jobs in warehouses and factories while applying for jobs back in New England, one of those long drives to Massachusetts had paid off. I had a few weeks to find a place to live and make one more drive, hauling my stuff to my first real apartment (aside from some obviously temporary places in college). I wound up in the second floor of a duplex two towns outside of Boston, above a couple nice enough guys I had nothing in common with and not remotely close to the friends I still had in the area. I was on my own.

***

A typical Home Movies episode revolves around Brendon (voiced by Small), Melissa (Melissa Bardin Galsky) and Jason (H. Jon Benjamin) arguing over the progress of whatever movie they’re working on, with their film’s story usually commenting on or subconsciously referencing whatever real-life issues they’re having at the time. Brendon’s mom — still named Paula despite the overhaul — vaguely pays attention but often has her own worries. And at some point, whether he seeks it out or not, Brendon will be subjected to the advice of his soccer coach, John McGuirk. Also voiced by Benjamin, McGuirk is the show’s most enduring character, a drunken fuck-up whose best friend is a child who barely tolerates him, a man of rage and regret and self-loathing with just enough self-delusion to get through the day. Benjamin voices Jason in a pinched-nose (and digitally tweaked) bleat; as McGuirk, he speaks in the instantly recognizable baritone from more famous cartoons. But while Bob Belcher is exasperated but stable and Sterling Archer is arrogant but needy, McGuirk is resigned and rueful. As Mike Cooley, singing with the Drive-By Truckers, said: “I’ve been falling so long, it’s like gravity’s gone and I’m just floating.”

Like any good sitcom, Home Movies develops other characters — surly teen guitar wizard Dwayne, gleeful bully Shannon, vile mama’s boy Fenton, stick-in-the-mud teacher Mr. Lynch, the psychotically inseparable Walter and Perry (who would be reconfigured into the G-rated Andy and Ollie of Bouchard’s Bob’s Burgers) — who can drop in to move an episode along, but the show is about this core of five not-quite-whole people. Brendon’s dad, Paula’s husband, is out of the picture for much of the show (when he is present he’s played by Louis C.K., who’s excellent as a guy who isn’t as mature as he thinks). Melissa’s father is beautifully voiced by Jonathan Katz, but her mother left a long time ago. Jason’s parents exist in theory but are never seen or heard (this, at least, is entirely for comedic effect) and McGuirk’s inability to begin, let alone maintain a relationship is made brutally obvious. These people often barely tolerate each other, but they’re what they’ve got. That, and the movies.

This all sounds horribly depressing;I don’t think I’ve done a good job here of conveying just how hilarious Home Movies was. The humor could be enhanced by despondency but also just by being fucking funny. Brendon, Melissa, and Jason would wander down who’s-on-first tangents when arguing over their movies, and the movies themselves were always founts of ludicrous strangeness — Jason’s furious pronunciation of “ROCKS!” while playing supervillain Pablo Picasso in Starboy and the Captain of Outer Space will just randomly pop into my head and make me laugh 15 years down the line. As will any number of McGuirk lines — “of course I’m drunk, that’s why I came to the mall,” for example. But so much of the show’s humor is accumulated, it can’t be explained without the context of its characters dealing with disappointments that could last a day or a lifetime and either pushing back or acquiescing with exasperated resolve. Their situations were outside my norms, but the emotions were true, and a frustrated truth is funnier than any lie.

***

I went to work, learned the ropes, got to know my co-workers. I generally hold back for a bit in new social situations where I’m going to presumably be with the same people for a while. I had known the friends I was missing now for the better part of a year in college before I was actually friends with them. I went to the bar with the guys downstairs once and watched them rock out to a lame cover band. I would rather have been at home listening to my mp3s, maybe the great Ass Ponys song “Kung Fu Reference,” which is about a lonely guy who gets drunk watching TV every night: “Dead soldiers line the road, along the coffee table/Blade Runner’s at the point where Rutger Hauer dies.”

Adult Swim was one of the things I watched a lot, and that’s where I encountered Home Movies again. I don’t remember which episode it was — my memory suggests it was the bonkers second season episode “History,” the entire first half of which is given over to the Picasso villainy of Starboy and the Captain of Outer Space — but it made me laugh with its unadulterated weirdness. By weirdness, I don’t mean the antagonistic comedic bafflement of a typical Adult Swim show (which can be great, don’t get me wrong), but the off-kilter existence of these characters who spend way too much time together making stuff, people with a shared, skewed frame of reference, for better and for worse. For a solid chunk of the time between 2000 and 2004, I’d spend anywhere from four to twelve hours a day in a run-down office, writing and editing and arguing with my friends about how to put out the next day’s newspaper, living in that world not despite its obsession and irritation but because of it. It turned out Home Movies had been up to something similar. So every Sunday I’d stay up until 1:30 in the morning, pop an old tape into my VCR and hit record when Home Movies came on and go to bed, waiting until the next day to catch up with what I’d been missing.

***

Home Movies ultimately lasted four seasons, and Small and Bouchard appear to have been willing to do more. But Adult Swim cut them off, much to their displeasure. The one silver lining is the network told them this ahead of time, and the show’s final episode, “Focus Grill,” is a true finale. And it’s one that holds a grudge — the story revolves around Brendon proudly showing the gang’s latest movie to a focus group of fellow kids (including the aforementioned Fenton, Walter, and Perry) only to have them tear it apart, often inarticulately and nonsensically. (“There’s no composition! The composition of the frames aren’t telling the story!” Fenton rages.) As they are prone to do, Brendon, Melissa, and Jason react badly,and in an effort to reconnect with their roots, they revisit their first movie only to find they never even finished it. A creative challenge ensues: each of the three will film their preferred ending for that first film — an Easy Rider knock-off that strands the trio at a crossroads, unsure where to go next — and let the focus group decide which is best.

While this is going on, McGuirk is attempting to assemble an overly large grill for Paula, who just wanted to cook a few burgers. Things are going slow but with the hope of success — as McGuirk tells Brendon, “I’m on my third beer. That’s when it all starts to get a little clearer.” The kids speculate on the possibility of McGuirk and Paula as a couple — he’s helping build a grill, which is a big deal — but aside from a suggestion at the very beginning of the series back in 1999, the two have almost no romantic chemistry. What they do have, though, is a similar outlook on life as something that will likely kick you when you’re down, an acceptance of that, and the shrugging understanding that you keep going even though it’s a bad idea. They’re not lovers, but the whole series has brought them together as friends.

But it’s also been pulling Melissa, Brendon, and Jason apart. Melissa, who is straight-laced and a bit of a goody-two-shoes, has nevertheless always been One of the Guys, and in this finale she’s experimenting with makeup — the more of it the better, she says, to the boys’ consternation. And in the ending she films, the biker concept is hilariously swept aside for Melissa’s character to be recognized as Princess Pretty (Brendon and Jason are turned into “handsome princes who are also excellent fighters”) and called back home by her long-lost mother. Jason’s ending is just as unfaithful to the biker story. He goes with his original idea at the time, the one he proposes all their movies end with, in which the Throw-Up Monster barfs everyone to death. (This is not too far from the great Michael O’Donoghue’s all-purpose ending “Suddenly, everyone was run over by a truck.”) The focus group hates both endings.

Melissa looks to an idealized future, Jason to the lost past. Brendon can see this and is just trying to hold onto the present. His ending actually completes the movie, in the most earnest way possible. The last lines of the original movie’s footage have Brendon’s character yelling, “We stay and fight, man!” In Brendon’s ending, he drops the battle but still takes a stand, with the gang turning their bikes (played in part by the various, still-unassembled grill parts) into a home:

Brendon: Not a great house, but our house.

Jason: Not really a house, but a pile of trash.

Melissa: Assembled out of random parts that were not intended to be put together,

Brendon: But a strong foundation, nonetheless, my friends.

Melissa: Yes. Though our windows are spoked and filthy and the door laden with bicycle grease, our foundation be solid.

Jason: Solid like our souls.

“We are strong together!” the trio shouts. The focus group boos this ending hardest of all.

***

My late night Home Movies recordings filled up tapes that used to house old Simpsons episodes. I knew those episodes, taped from reruns during high school in the late ’90s, by heart at that point; it was more important to get this new show that was speaking to me now just as strongly as that show did then. I’d rewind the tape on Monday in a 22-year-old single dude’s living room, all empty floor and bare walls, shelves made from pine boards and concrete blocks — A room not unlike McGuirk’s, come to think of it —where he would stay up and get blitzed and order swords from the home shopping networks. And then, hungover and flat broke (because of ordering goddamn swords), try to exchange the blades for food at the supermarket. Is not getting that bad an accomplishment? I’ll say it is.

I hung out with Jason, Melissa, and Brendon, drank with Paula and McGuirk, and taped every episode I could. I got about 75 percent of the show’s 52 episodes this way. But I never saw the finale. And the following fall, I moved back to Boston and reconnected with some of those friends from college. I kept those tapes, though. And when the show was released on DVD, I snapped it up and watched from the beginning, anticipating and fearing the ending I barely remembered.

***

Brendon’s ending to the gang’s first movie is corny as shit, and I have teared up watching it more times than not. And even if he and Jason and Melissa can’t agree on how to end the movie, they can agree that the focus group sucks ass and they give them the boot. But this is a crossroads, and they can feel it. They sit around watching old clips while “Sunset Theme” (the best of Small’s many fantastic musical contributions to the show and the one that plays under the ending of Season 2 classic “Fenton’s Party”) hums in the background. Earlier in the episode, Brendon talks with McGuirk about the difficulty of ending things and the two obliquely describe the show’s history; here Home Movies indulges in what it’s accomplished. And then Brendon wonders what the point of it all is:

Brendon: This is gonna sound really weird, guys, I don’t…honestly…I don’t think our movies should be watched.

Melissa: They shouldn’t?

Brendon: No.

Melissa: Then why are we making them?

Brendon: I have no idea. All I know is this: we keep coming here after school every single day and we just keep doing it. And I don’t know…and we just do it and it feels like we should just be doing it, I guess, I don’t know.

Jason: (sighs) Weird. Weird. We are…God, we’re weird.

Melissa: What’s wrong with us?

Brendon: I don’t know!

Jason: We’re weirdos!

Was the volume turned up on that newsroom TV in Washington, D.C.? Did I hear this in the back of my head while the rest of me was thinking about Olympia Snowe or Susan Collins or some other worthless bullshit? Because this is what I had been missing so much, the day after day of making something together with my fellow weirdos. It just felt like we should be doing it, I guess. But we weren’t.

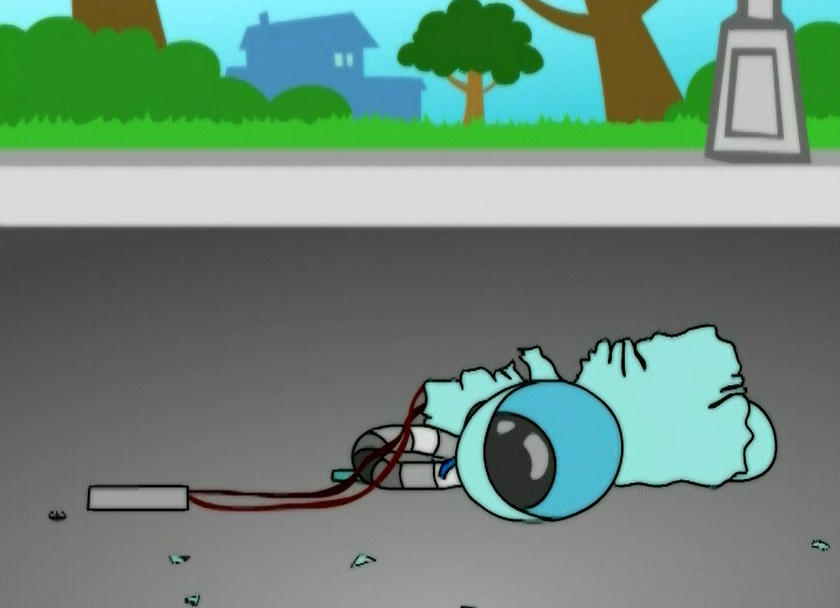

As they’re rewatching their greatest hits, the kids are called away to witness, along with Paula, McGuirk’s lighting of the grill. Which of course explodes, possibly taking the house with it. The show cuts to Brendon filming out the window of McGuirk’s car, where everyone — Paula, Melissa, Jason — is still alive, if covered in soot and burns. Then the car hits a pothole and Brendon drops the camera into the road. Where it’s immediately run over by another car.

The movies of Home Movies were almost certainly lost in the explosion, and now the tool to create them has been destroyed. Brendon is at a loss for words — wanting to tell everyone what happened but unable to because of how traumatic it is — but McGuirk, however, is not. Since they’re obviously not grilling, he asks what everyone wants to eat and the rest of the car, minus Brendon, starts furiously debating various cheap food options. McGuirk yells at them to shut up. Then he proposes tapas. Brendon swallows whatever he was going to say about his camera and enters the conversation: “I could go for tapas.” Everyone starts talking again, another argument in a show full of them, but with the consensus tilting towards bite-sized Spanish food. In the show’s last moment, what caught my eye so long ago, the camera films a few last flickering images and dies.

***

In high school, I had weirdo friends. It took a little bit, but I found more weirdos in college. I’ve worked several places since that first real job 15 years ago, nearly always with decent day-to-day co-workers. I worked at a few places for several years and have no idea where the people I worked with are now. And I worked at other places with weirdos. I’m still friends with those folks, like I am with college and high school friends. Not all of them, but weirdos tend to hang onto each other.

Brendon loses his work, but the show makes it clear that he also chooses to let that work go. Whatever he does after tapas, it’s unlikely making movies will be a part of his life in the same way. But he still has his friends. His family. His weirdos. You find a solid group of weirdos and they can outlast the work that you forge your friendship in. And that’s good, because that work won’t always be there. It gets blown up or canceled, or maybe chiseled away bit by bit by people who don’t understand the value of the work, how it has meaning in itself and how it brings the weirdos behind it together. But the weirdos know what it means, what it meant. It’s so hard to move on from what you know. You have to do it but you can’t do it alone. To all of my weirdos out there, then and now, I miss you and I love you. We were strong together. We are strong together.

Hat tip to Toonzone for the transcriptions.